Consider the Russo-Japanese War, renewed anarchy in Macedonia, the intervention of England, the financial scheme, the Moroccan imbroglio, the royal meetings of 1907, the judicial reforms for Macedonia, and finally the Anglo Russian agreement of 1907.

Continuing Austria-Hungary Annexes Bosnia-Herzegovina,

our selection from The Balkan Problem by Major Archibald Colquhoun published in around 1908. The selection is presented in 2.5 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Austria-Hungary Annexes Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Time: 1908

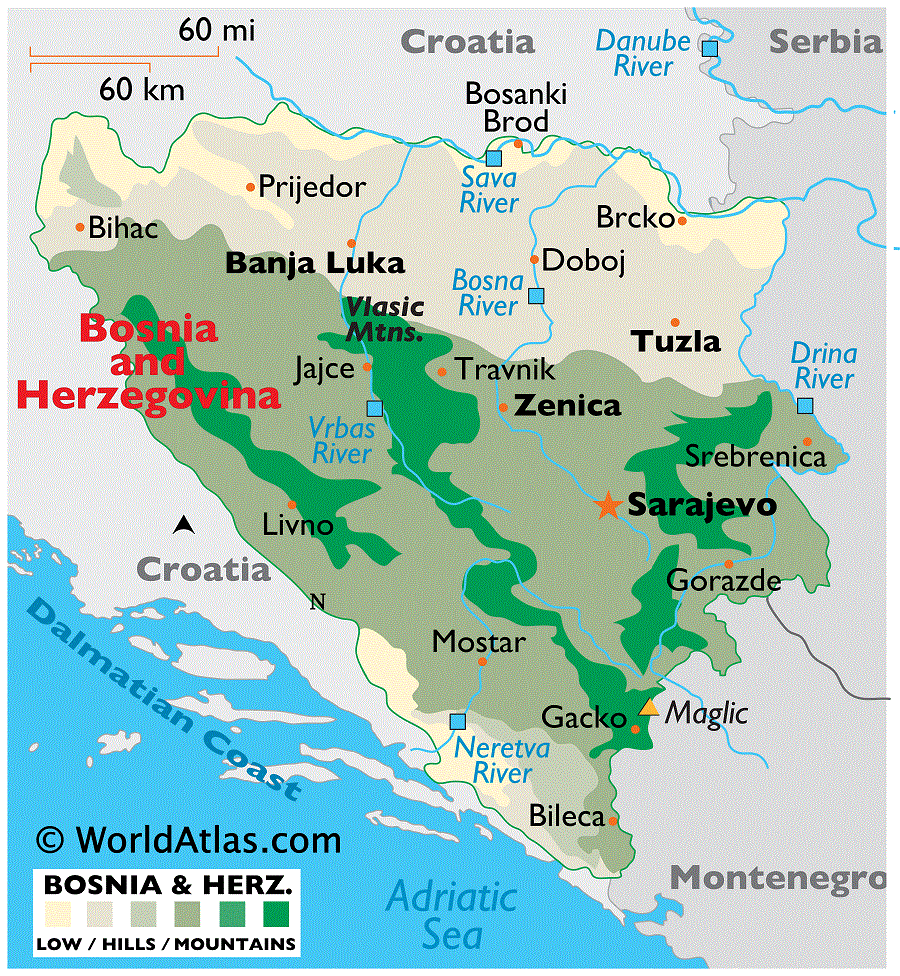

Place: Bosnia-Herzegovina

Turning to the events which led up to the present Balkan crisis, one needs to take a comprehensive view of the situation in order to fit the actors into their proper places. The domination of the Balkans and an outlet on the Aegean -— this is the prize. Germany and her avant – garde, Austria-Hungary, play for it on one hand, Russia on the other. Russia purchased the neutrality of Austria during the Russo-Turkish war by the secret convention of January 15, 1877, which gave in advance the status in Bosnia-Herzegovina which the Treaty of Berlin afterward formally confirmed. The acquiescence of King Milan, of Serbia, was secured by a promise, formally ratified, that after a while his country should be permitted to expand into “Old Serbia” — the Macedonian vilayets. Sometime later he learned that a similar pledge had been given to Bulgaria. M. Victor Bérard, in “La Révolution turque,” gives a succinct description of conflicting policies at this period. Great Britain and France wanted to Europeanize Turkey, acting through the central Government. Austria and Russia, on the contrary, desired a surgical operation— “autonomie ou anatomie.” Then followed “les belles années pour l’entente Austro-Russe,” developing into the Mürzsteg program and the so-called “mandate” to Austria and Russia. Important events, some of them epoch-making, succeeded each other rapidly-the Russo-Japanese War, renewed anarchy in Macedonia, the intervention of England, the financial scheme, the Moroccan imbroglio, the royal meetings of 1907, the judicial reforms for Macedonia, and finally the Anglo Russian agreement of 1907, which, M. Bérard declares, put an end to the Austro-Russian monopoly.

The first sign of independent or rather competitive action was the railway war. Austria announced the concession from Turkey for a line to run through the sandjak of Novi Bazar, designed to connect the Bosnian system with Mitrovitza and Salonica. A storm rose among the southern Slavs; and Russia replied with a counter-project for a Slav line from the Danube to the Adriatic. Bulgaria pressed for the connection of her system not yet completed. Italy expressed her desire for a line from the coast opposite Brindisi to Monastir. While the excitement caused by these projects was still simmering, the Turkish revolution, like a thunderbolt, altered the whole situation; and hardly had the reverberations died away when a fresh complication arose.

It is tolerably certain that, although Austria recognized the necessity, in view of a reformed Turkey, of making permanent the hold she had established in Bosnia, she would never have chosen such a time and method for announcing her intention had not Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria forced the pace. Having been assured of Austro-German support for his pretensions to independent Czardom, in return for neutrality in regard to a step which was bound to embitter the rest of the Slay world and particularly the southern Slavs, Prince Ferdinand thought a bird in the hand worth two in the bush, crossed the Rubicon, and left his confederate Aehrenthal to follow with the annexation, to arrange with Turkey, and to meet the reproaches of Europe. Moreover, the astute diplomatist of Sofia, after arranging his difference with Turkey, executed a sort of double insurance, and in a triumphal visit to St. Peters burg reaffirmed the quondam reliance of Bulgaria on Russia. Subsequently it was announced that not only public opinion, but Government policy in Bulgaria was inclined to support Serbia.

At this point it is necessary to consider the position of Serbia herself. Although it has suited Austria to represent Serbia’s futile intervention as gratuitous, she had an irrefutable claim to a hearing. Her position was settled by the Treaty of Berlin, without regard to her aspirations; but the Powers who settled that position had also a moral responsibility toward the little kingdom that she should not be stifled or starved by her politico-geographic conditions. Before the Treaty of Berlin she had access through Turkish territory to the Adriatic; but the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina drew an Austrian cordon round two sides of her; and her only other outlets were the long journey by the Danube (also controlled at the Iron Gates by Austria) and the Salonica railway whose freights are prohibitive to agricultural produce or cattle, which are Serbia’s only exports. Serbia became, therefore, the economic prisoner of Austria; and any attempts to find other markets than those of Austria were frustrated. The “pig war,” which seemed comic to Europe at large, was life or death to the Serbian farmer.

When, therefore, Serbia perceived that her economic disadvantage was to be perpetuated, she lost her head in the fervor of patriotic indignation and made a fatal mistake. This was the claim for territorial compensation in the shape of a strip of land in Bosnia which would give Serbia connection with Montenegro and access to the Adriatic. Had Austria made it plain at this juncture that, beyond the annexation of provinces already under her control, for which she was prepared to pay a monetary compensation to Turkey, she had no ulterior motives, the crisis might have passed. But Serbia’s blunder, and the indiscretions of her press and her Crown Prince, gave an opportunity for a “lesson to the Slavs,” which Baron Aehrenthal and his supporters in Budapest and Berlin were not sorry to seize. Accordingly, it was declared that Serbia’s attitude was a menace to Austria; and it became clear that Serbia had no course open save to “eat the leek,” submit to disarmament or risk all upon a desperate hazard.

Were it simply a question of Austria-Hungary, a great military power with an aggressive policy, pitted against Serbia, an agricultural state with no policy at all, the conclusion would be foregone. But no move in the Balkan game is really isolated; and the present situation is no exception. Here we see Teuton and Slav again in conflict. The struggle of Austro-Germanic and Russian influence for predominance in the Balkans had entered a fresh stage. Serbia and Bosnia are pawns in the game; Bulgaria has achieved the dignity of knighthood, and shares with Poland the honor of being one of the two pivots on which the situation turns.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Emil Reich began here. Major Archibald Colquhoun began here.

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.