Appreciate the attitude of Austria-Hungary, not as a State but as a conglomeration of nationalities.

Continuing Austria-Hungary Annexes Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Today is our final installment from Emil Reich and then we begin the second part of the series with Major Archibald Colquhoun. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Austria-Hungary Annexes Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Time: 1908

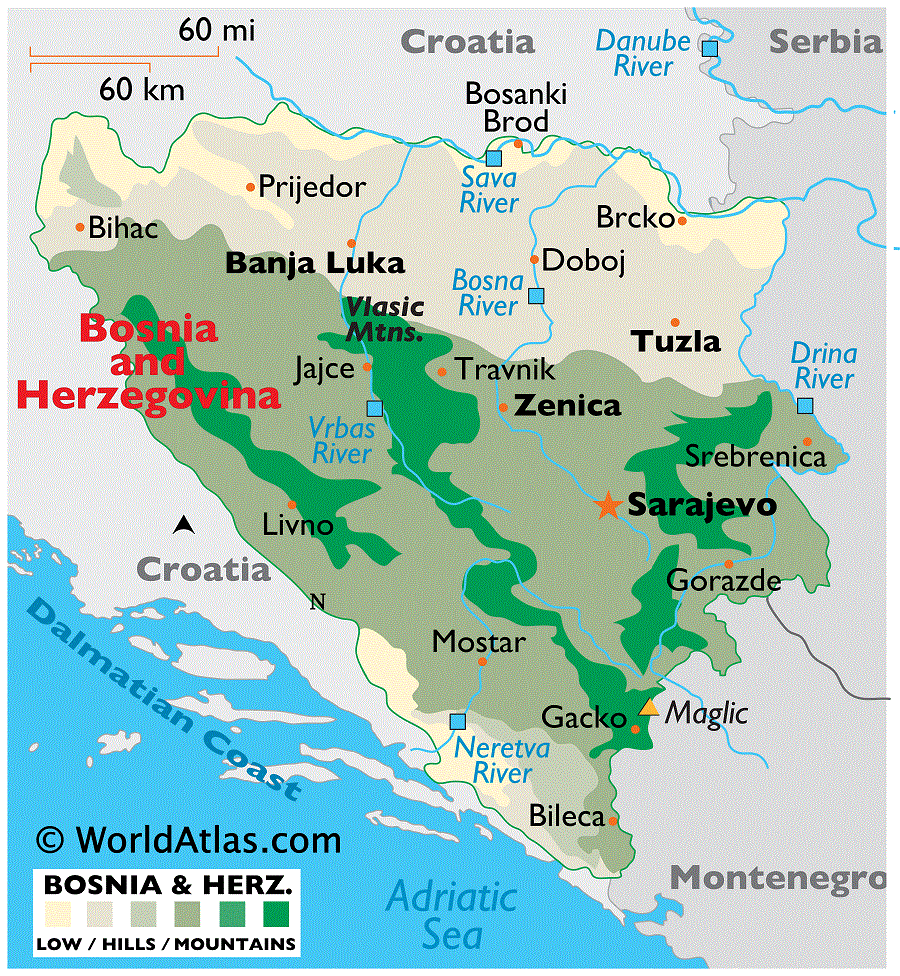

Place: Bosnia-Herzegovina

The process of crystallization repeatedly referred to as the feature of contemporary politics in the Southeast of Europe, has been proceeding with such rapidity that a formal and cordial understanding between Turkey and Bulgaria is now almost a certainty, if not a fait accompli. In Bulgaria, too, the historic growth of events and facts so outstripped the growth of legal doctrines that it became, for Prince Ferdinand and his people, a mere matter of necessity to render the situation more defined and clear by articulating the facts in the form of an imperatively needed declaration of independence. The Turks themselves have admitted this much by their deeds and their conciliatory attitude to Bulgaria, if not by words. As soon as hopeful negotiations were started by the former vassal and suzerain, all Europe applauded both the magnanimity of the Turk and the boldness of the Bulgarians. Under these circumstances it is not necessary to add any further details to a question the satisfactory solution of which is close at hand.

As regards the various aspirations of the Serbians, it is difficult to see what “compensation” the Powers in conference could possibly offer them. Territorial compensation could be given only at the expense of the Turks or of Austria-Hungary. The former is excluded by the official declaration of Great Britain, France, and Russia; the latter cannot seriously be thought of for a moment, in that it would constitute the classical casus belli in the Balkans. Serbia will, no doubt, obtain a seat on the Danube Commission and certain privileges not accorded her in the Treaty of 1883. Her Pan — Slovene or Pan — Serbian aspirations are for the time being doomed to failure. In all the preceding statements of fact regarding the revolutionary actions of Serbia in Austro-Hungarian territory, I did not at all mean to sit in moral judgment on a nation so old, so valiant, and so gifted. I stated the facts; I drew the logical conclusion from them; but it is far from me to condemn the Serbians altogether. They try to do what all nations attempt doing: they want to assert themselves. According to the geographical and historical situation in space and time, each nation does that in its own way. All I claimed was the right of Austria-Hungary to do it in her way.

The upshot, then, of the much-maligned actions of Austria Hungary on the one hand, and of Bulgaria on the other, is this, that the perennial crisis in the Near East has been advanced by several most important steps toward a permanent regulation and crystallization of the indistinct, amorphous, and thus dangerous situation in the Balkans. Turkey may perhaps effectively claim some financial indemnification from Austria-Hungary; at any rate, she can obtain again full control of the Samjak of Novibazar, which Baron Aehrenthal spontaneously offers to her. She may also hope to improve her international position by an abrogation, or partial reformation, of her Capitulations. The question of the Dardanelles will not be raised at present. Crete is in reality no difficulty whatever. War has been obviated, and no substantial damage has been entailed on any one of the Powers, great or small. Has crisis ever been more salutary? Can the statesman by whose thought and promptitude the larger part of this so-called crisis has been brought about be characterized by no fitter title than that of a law-breaker? To him and to many an anonymous politician in the Balkans all Europe owes no small gratitude for the clearing of a political horizon on which ominous storm-clouds used to gather with fatal celerity. The amour propre of several Powers may have felt uneasy as long as the necessities under which Baron Aehrenthal acted were not known. It is hoped that these necessities will now be understood with somewhat greater readiness.

Now we begin the second the second part of our series with our selection from The Balkan Problem by Major Archibald Colquhoun published in around 1908. The selection is presented in 2.5 easy 5-minute installments.

Any attempt to look at the Near East from the point of view of the Austro-Hungarian nationalities is rendered especially difficult by the fact that questions of foreign policy are excluded from parliamentary debates in those countries. The only assembly in which such subjects can be discussed is the so-called “Delegations,” two bodies composed of members representing in equal proportions the Austrian Empire and the Hungarian Kingdom. One-third of the members of the Austrian Delegation are chosen by the Upper Chamber of the Reichsrath, and are usually men connected with the Imperial Court; while the rest, chosen by the Second Chamber, are mainly ex-ministers and lawyers and soldiers of high professional rank. The Christian Socialist party, which is really the Clerical party under a new guise, represents the only democratic element; and now that the Austrian Government has adopted a Clerical attitude, it is assured of their support. The attitude of the Hungarian Delegation seems to be equally favorable to a “Clerical” policy (and in Bosnia-Herzegovina the Clerical attitude has predominated); while other reasons, to be touched on hereafter, secure the support of Hungary for Baron Aehrenthal’s views. Not even from the Bohemian members of the Delegation is severe criticism to be expected; and the result is that, with grave internal dissensions on the subject, Austria-Hungary is able to present an unruffled front to the world in the matter of her foreign policy.

It is, however, necessary to penetrate beneath the official surface in order to appreciate the attitude of Austria-Hungary, not as a State, but as a conglomeration of nationalities, toward the Near-Eastern question. While it would be impossible in the limits of this article to give any idea of the numberless eddies and torrents which go to make up the “Whirlpool of Europe,” we may endeavor to trace some of the main currents, and to show how they are setting at the present time. It is, of course, a truism to say that these internal conditions, this play and interplay of conflicting forces, have been determining factors in deciding the policy which has recently brought Europe to the verge of war. The strained relations between the two halves of the Dual Monarchy rendered necessary some definite and decisive action on the part of Austria; and the question of the subject nationalities —- a burning one in both Austria and Hungary —- is inextricably bound up with the Balkan policy of the great Powers.

The Slavs, and their inconvenient national obstinacy, form internal problems for Austria, Hungary, and Germany; and, of these three, the first alone has acted with real state craft in placating, instead of irritating, that nationalism. Nevertheless, it is Austria-Hungary that appears just now as the aggressor, thus ranging herself definitely on the German side in the struggle of Teuton versus Slav. That Hungary should give countenance to anything projected by Austria at the present stage; nay more, that she should actually suspend hostilities and help to “keep the ring,” is sufficiently significant. One need not look far for the explanation of her attitude. Hungary, in the words of Bismarck, quoted by M. René Henry, is “nothing but an island in the middle of a vast sea of Slav peoples; and, having regard to her numerical inferiority, she can only secure her safety by leaning on the German element in Austria and on Germany.” An impression exists that Hungarians are necessarily anti-German because of their struggle with the German house of Hapsburg and its influences; but, having won this fight, the Magyar seems to be convinced that the Slav, not the German, constitutes the true danger. It must not be forgotten that, as part of the historic lands of the Hungarian Crown, Bosnia Herzegovina should eventually be restored to the Magyar State; but no inconvenient stress has been laid on this at present. It would certainly not help to solve Hungary’s difficulties that two million Slavs should be added to her.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Emil Reich began here.

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.