Nor can it be a mystery to whosoever studies the latest history of the Serbian aspirations that they have long since learned to use the assassin’s knife as an ordinary political weapon.

Continuing Austria-Hungary Annexes Bosnia-Herzegovina,

with a selection from Crisis in the Near East by Emil Reich published in around 1908. This selection is presented in 5.5 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Austria-Hungary Annexes Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Time: 1908

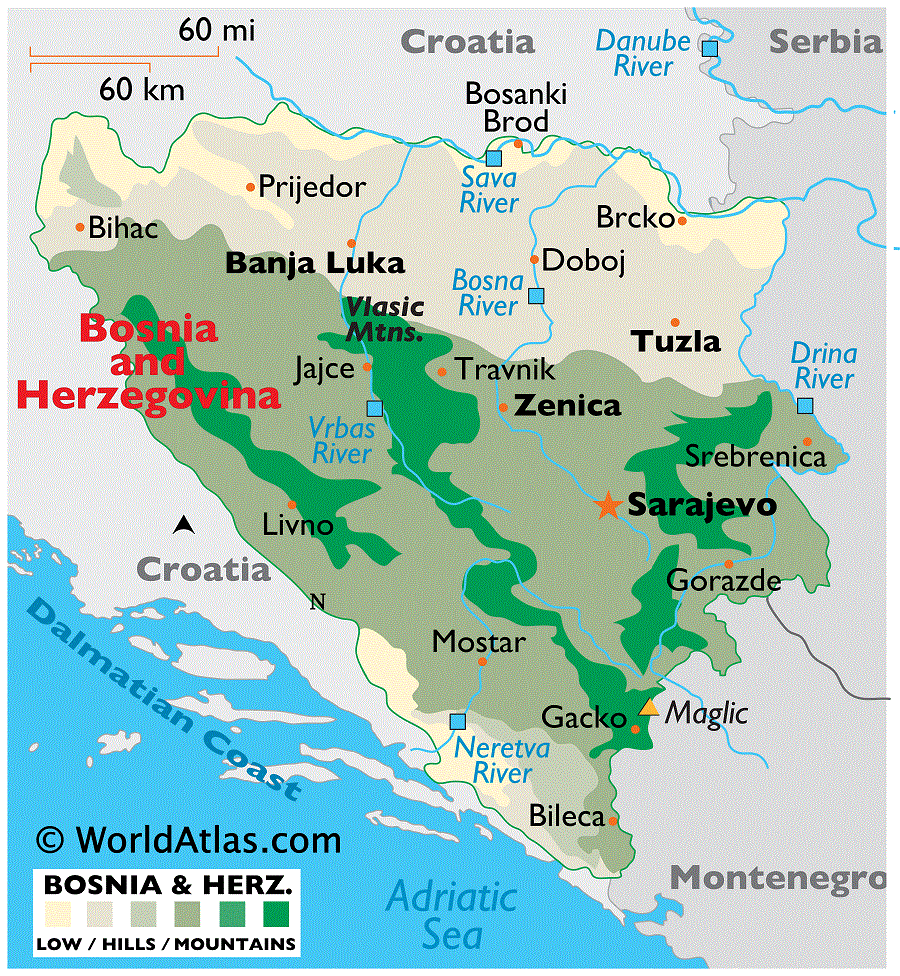

Place: Bosnia-Herzegovina

So far, we have considered only the verbal activity of the relentless foreign enemies of the Austro-Hungarian régime in Bosnia and Herzegovina. If now we go to their deeds, we are at the outset confronted with the fact that no fewer than 15,000 Mauser rifles and bombs made in the artillery arsenal of Kragujevatz in Serbia were, in autumn, 1907, brought by the conspirators to the frontiers of Bosnia and there deposited in a blockhouse called Krajtchinovacz, as also in the Serbian monastery of Banja near Priboj. Some of those bombs were sent to Montenegro, where they were seized by the authorities on the 5th of November, 1907. The Serbian conspirators, it appears, wanted to exterminate the members of the family of the Prince of Montenegro, together with that Prince, so as to facilitate thereby the union of all the Western Balkans, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, under the leadership of a Serbian dynasty. Serbian bands, under a Serbian ex-Minister of War, whose name was General Atanatzkovich, and with the moral and material support of Serbian patriotic associations, such as the “Srpska Bratsha” and the “Kolo Srpskich Sestara,” raided Austro-Hungarian territory. Officially, of course, the existence of these bands was repeatedly denied. It is nevertheless beyond a doubt that Serbian officers and Serbian soldiers were, with the connivance of the Serbian Government, sent into Macedonia, as well as into the regions bordering on Bosnia and Herzegovina, with the manifest object to create mischief and spread the spirit of revolt. Fethi Pasha, the Turkish envoy at Belgrade, knew every movement of those bands, and M. Simich, one of the most active of the Serbian agitators, made no secrets about them to earnest inquirers. Nor can it be a mystery to whosoever studies the latest history of the Serbian aspirations that they have long since learned to use the assassin’s knife as an ordinary political weapon. It is, among other things, an ascertained fact that Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria has, as a rule, and certainly since 1904, abandoned any intention of traveling through Serbian territory, except in profound secrecy, and with the passport of a merchant. At Sofia they will, so they say, not be surprised to find some day or other the same sort of bombs, filled with “Schneiderit” or with “Wassit,” that were found at Cetinje, in Montenegro.

These, then, were the facts staring the Austro-Hungarian Government in Bosnia-Herzegovina in the face. There was in 1907 and 1908, to the exclusion of any reasonable doubt, a wide and dangerous revolutionary movement among the South Slavs, the one clear and unmistakable object of which was to “liberate” the Slovenes, Croatians, and Serbians, i.e., among others, the Bosniaks and Herzegovinas, from the “yoke” of Austro-Hungarian sovereignty. I do not for a moment hesitate to admit that had Bosnia and Herzegovina been an internationally acknowledged member of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, such as is Styria or Carinthia, the revolutionary activity of the Pan-Slovenes, or Pan-Serbians, could have been readily dealt with by Austria-Hungary without her drawing upon ultimate resources of diplomacy, and without leaving the ordinary way of quelling disturbances. It cannot, on the other hand, be denied that under the actual circumstances in 1907 and early in 1908 Austria-Hungary was most seriously handicapped in her natural desire to defend her sphere of legitimate governance. Once Bosnia and Herzegovina are formally annexed by the Dual Monarchy, it is comparatively easy to foil or reduce revolutionary movements by the legal means of repression. But as long as Austria Hungary is not, in law as well as in fact, the acknowledged sovereign of the two provinces, she is not in a position to strike firmly. A Serbian intriguing in Bosnia is, legally, intriguing in Turkish territory. How can, under the circumstances, Austria-Hungary take him to task with becoming severity and expedition? One hesitates; one compromises; that is, one renders the situation more and more embroiled and more and more weak. If, again, one is provoked beyond the limit of endurance, as undoubtedly Austria-Hungary has been by the Slovene revolutionaries, then nothing remains but war proper. To the incessant cabals and plots of the Slovenes and Serbians the Austro-Hungarian Government could have replied in one way only — by marching on Belgrade. This means war and would have been only another confirmation of the experience which Austria-Hungary had in 1878, when, despite the mandate of the Powers, she had to conquer the two provinces by a regular campaign. I do not in the least attempt to press this point. Yet it is perfectly clear that, just as Austria-Hungary was obliged to possess herself of Bosnia and Herzegovina by right of war, or droit de conquête, even so she would have unavoidably been driven to maintain that conquest by a new war with the South-Slavs. This much the most prejudiced of her critics cannot but admit.

When things had come to that pass, when war seemed the only issue out of an intolerable situation, the Turks by their otherwise admirable political revival precipitated events in such a manner that a statesman of the caliber of Baron Aehrenthal had no other choice left. By the introduction of constitutional government into Turkey it became at once manifest that the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina might claim to be represented in the Parliament of Constantinople. As a matter of fact agitators have claimed it; see especially the “Srpska Riječ” of the 22nd of September, 1908. Nor could it be said that the law of Europe was formally against such claims. In reality it strengthened, nay encouraged, such claims. For were not Bosnia and Herzegovina still Turkish in law? The new Constitution in Turkey thus added a most dangerous weapon to the arsenal of the countless foreign enemies of and secret plotters in Austro-Hungarian Bosnia and Herzegovina. The time had come. Austria – Hungary needed a fait accompli to obviate war, and to render her position at least endurable. To submit the question to a Conference would have involved months, perhaps years, of negotiations, without absolutely insuring peace. In an ever famous case Austria-Hungary had acquired the conviction that even the formal previous consent of the Powers, obtained by means of laborious and costly negotiations, did not obviate the terrible war of the Austrian Succession. On the other hand, a firm action would, it was confidently hoped, obviate war. The events have justified this expectation. Can it be seriously called in question that Austria-Hungary has, by its act, rendered war in the Balkans a matter of very doubtful possibility? That process of crystallization which has in the last thirty years been the dominating principle of the historic growth of the Balkans; that process making for clearness, accurate delimitation of power, and peace —- that process was understood and acted upon by Baron Aehrenthal. Is that really a crime? Is an act based on the prompt understanding of the meaning of historic currents or ideas to be considered an infraction of the law of nations? Above the law of nations there is the history of nations and its superior law.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Emil Reich begins here. Major Archibald Colquhoun begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.