Darius chose a place calculated to give the larger of two armies the full advantage of numerical superiority.

Continuing Alexander the Great Wins Battle of Gaugamela,

our selection from Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Sir Edward S. Creasy published in 1851. The selection is presented in nine easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Alexander the Great Wins Battle of Gaugamela.

Time: 331 BC

Place: East of Mosul, Iraq

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

In Upper Asia, beyond the Euphrates, the direct and material influence of Greek ascendency was more short-lived. Yet, during the existence of the Hellenic kingdoms in these regions, especially of the Greek kingdom of Bactria, the modern Bokhara, very important effects were produced on the intellectual tendencies and tastes of the inhabitants of those countries, and of the adjacent ones, by the animating contact of the Grecian spirit. Much of Hindu science and philosophy, much of the literature of the later Persian kingdom of the Arsacidæ, either originated from or was largely modified by Grecian influences. So, also, the learning and science of the Arabians were in a far less degree the result of original invention and genius than the reproduction, in an altered form, of the Greek philosophy and the Greek lore acquired by the Saracenic conquerors, together with their acquisition of the provinces which Alexander had subjugated, nearly a thousand years before the armed disciples of Mahomet commenced their career in the East.

It is well known that Western Europe in the Middle Ages drew its philosophy, its arts, and its science principally from Arabian teachers. And thus, we see how the intellectual influence of ancient Greece, poured on the Eastern world by Alexander’s victories, and then brought back to bear on medieval Europe by the spread of the Saracenic powers, has exerted its action on the elements of modern civilization by this powerful though indirect channel, as well as by the more obvious effects of the remnants of classic civilization which survived in Italy, Gaul, Britain, and Spain, after the irruption of the Germanic nations.

These considerations invest the Macedonian triumphs in the East with never-dying interest, such as the most showy and sanguinary successes of mere “low ambition and the pride of kings,” however they may dazzle for a moment, can never retain with posterity. Whether the old Persian empire which Cyrus founded could have survived much longer than it did, even if Darius had been victorious at Arbela, may safely be disputed. That ancient dominion, like the Turkish at the present time, labored under every cause of decay and dissolution. The satraps, like the modern pachas, continually rebelled against the central power, and Egypt in particular was almost always in a state of insurrection against its nominal sovereign. There was no longer any effective central control, or any internal principle of unity fused through the huge mass of the empire and binding it together.

Persia was evidently about to fall but, had it not been for Alexander’s invasion of Asia, she would most probably have fallen beneath some other oriental power, as Media and Babylon had formerly fallen before herself, and as, in after-times, the Parthian supremacy gave way to the revived ascendency of Persia in the East, under the scepters of the Arsacidæ. A revolution that merely substituted one Eastern power for another would have been utterly barren and unprofitable to mankind.

Alexander’s victory at Arbela not only overthrew an oriental dynasty but established European rulers in its stead. It broke the monotony of the eastern world by the impression of western energy and superior civilization, even as England’s present mission is to break up the mental and moral stagnation of India and Cathay by pouring upon and through them the impulsive current of Anglo-Saxon commerce and conquest.

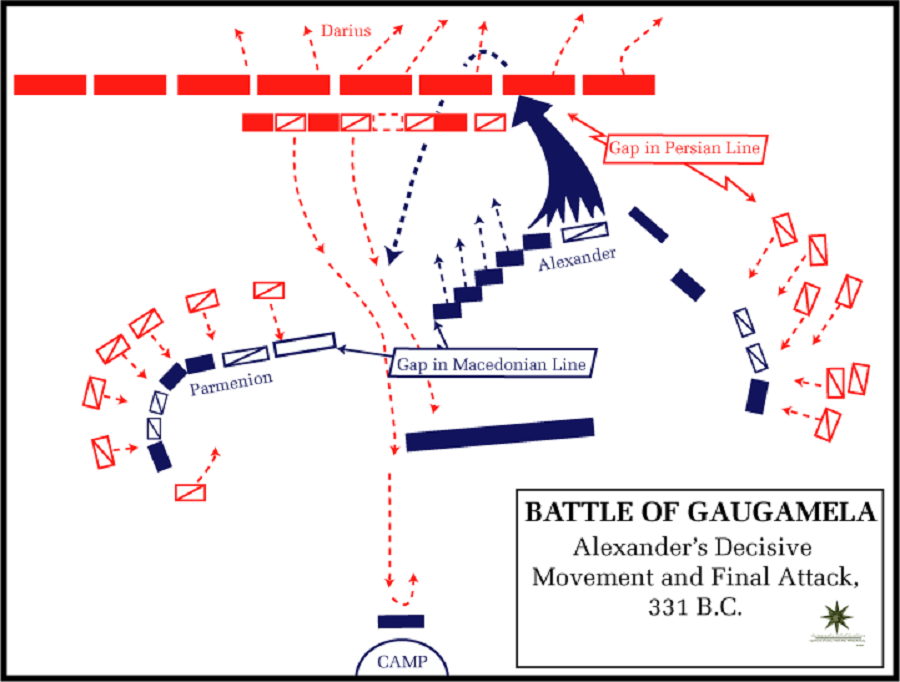

Arbela, the city which has furnished its name to the decisive battle which gave Asia to Alexander, lies more than twenty miles from the actual scene of conflict. The little village, then named Gaugamela, is close to the spot where the armies met, but has ceded the honor of naming the battle to its more euphonious neighbor. Gaugamela is situated in one of the wide plains that lie between the Tigris and the mountains of Kurdistan. A few undulating hillocks diversify the surface of this sandy tract; but the ground is generally level and admirably qualified for the evolutions of cavalry, and also calculated to give the larger of two armies the full advantage of numerical superiority.

The Persian King — who, before he came to the throne, had proved his personal valor as a soldier and his skill as a general — had wisely selected this region for the third and decisive encounter between his forces and the invader. The previous defeats of his troops, however severe they had been, were not looked on as irreparable. The Granicus had been fought by his generals rashly and without mutual concert; and, though Darius himself had commanded and been beaten at Issus, that defeat might be attributed to the disadvantageous nature of the ground, where, cooped up between the mountains, the river, and the sea, the numbers of the Persians confused and clogged alike the general’s skill and the soldiers’ prowess, and their very strength had been made their weakness. Here, on the broad plains of Kurdistan, there was scope for Asia’s largest host to array its lines, to wheel, to skirmish, to condense or expand its squadrons, to maneuver, and to charge at will. Should Alexander and his scanty band dare to plunge into that living sea of war, their destruction seemed inevitable.

Darius felt, however, the critical nature to himself as well as to his adversary of the coming encounter. He could not hope to retrieve the consequences of a third overthrow. The great cities of Mesopotamia and Upper Asia, the central provinces of the Persian empire, were certain to be at the mercy of the victor. Darius knew also the Asiatic character well enough to be aware how it yields to prestige of success and the apparent career of destiny. He felt that the diadem was now either to be firmly replaced on his own brow or to be irrevocably transferred to the head of his European conqueror. He, therefore, during the long interval left him after the battle of Issus, while Alexander was subjugating Syria and Egypt, assiduously busied himself in selecting the best troops which his vast empire supplied, and in training his varied forces to act together with some uniformity of discipline and system.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.