Great reliance had been placed by the Persian King on the effects of the scythe-bearing chariots.

Continuing Alexander the Great Wins Battle of Gaugamela,

our selection from Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Sir Edward S. Creasy published in 1851. The selection is presented in nine easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Alexander the Great Wins Battle of Gaugamela.

Time: 331 BC

Place: East of Mosul, Iraq

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

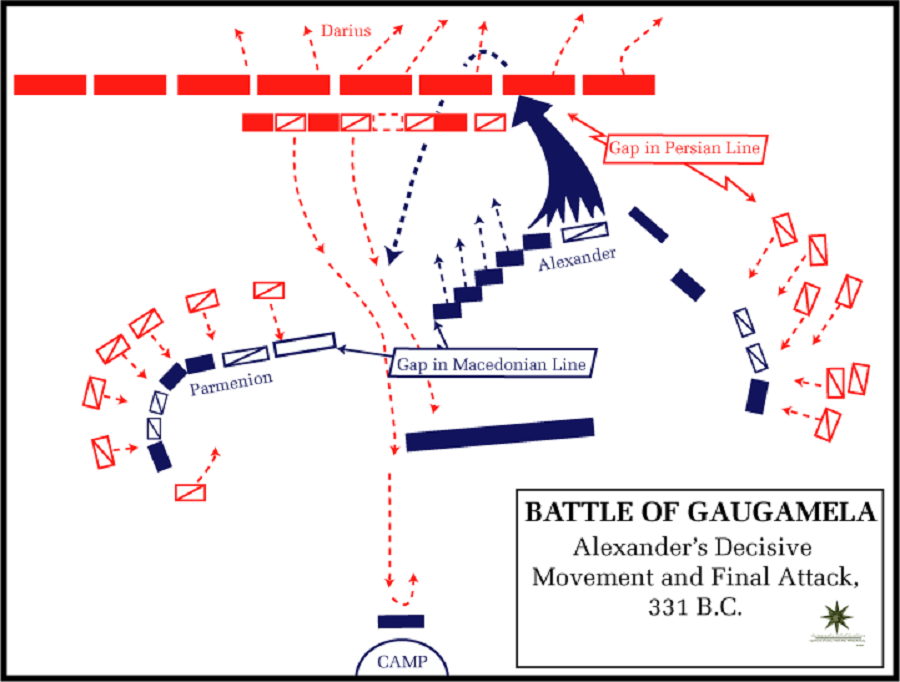

There was deep need of skill, as well as of valor, on Alexander’s side; few battlefields have witnessed more consummate generalship than was now displayed by the Macedonian King. There were no natural barriers by which he could protect his flanks; and not only was he certain to be overlapped on either wing by the vast lines of the Persian army, but there was imminent risk of their circling round him, and charging him in the rear, while he advanced against their center. He formed, therefore, a second, or reserve line, which was to wheel round, if required, or to detach troops to either flank, as the enemy’s movements might necessitate; thus, with their whole army ready at any moment to be thrown into one vast hollow square, the Macedonians advanced in two lines against the enemy, Alexander himself leading on the right wing, and the renowned phalanx forming the center, while Parmenio commanded on the left.

Such was the general nature of the disposition which Alexander made of his army. But we have in Arrian the details of the position of each brigade and regiment; and as we know that these details were taken from the journals of Macedonian generals, it is interesting to examine them, and to read the names and stations of King Alexander’s generals and colonels in this the greatest of his battles.

The eight regiments of the royal horse-guards formed the right of Alexander’s line. Their colonels were Clitus — whose regiment was on the extreme right, the post of peculiar danger — Glaucias, Ariston, Sopolis, Heraclides, Demetrias, Meleager, and Hegelochus. Philotas was general of the whole division. Then came the shield-bearing infantry: Nicanor was their general. Then came the phalanx in six brigades. Coenus’ brigade was on the right, and nearest to the shield-bearers; next to this stood the brigade of Perdiccas, then Meleager’s, then Polysperchon’s; and then the brigade of Amynias, but which was now commanded by Simmias, as Amynias had been sent to Macedonia to levy recruits. Then came the infantry of the left wing, under the command of Craterus.

Next to Craterus’ infantry were placed the cavalry regiments of the allies, with Eriguius for their general. The Thessalian cavalry, commanded by Philippus, were next, and held the extreme left of the whole army. The whole left wing was entrusted to the command of Parmenio, who had round his person the Pharsalian regiment of cavalry, which was the strongest and best of all the Thessalian horse regiments.

The center of the second line was occupied by a body of phalangite infantry, formed of companies which were drafted for this purpose from each of the brigades of their phalanx. The officers in command of this corps were ordered to be ready to face about if the enemy should succeed in gaining the rear of the army. On the right of this reserve of infantry, in the second line, and behind the royal horse-guards, Alexander placed half the Agrian light-armed infantry under Attalus, and with them Brison’s body of Macedonian archers and Cleander’s regiment of foot. He also placed in this part of his army Menidas’ squadron of cavalry and Aretes’ and Ariston’s light horse. Menidas was ordered to watch if the enemy’s cavalry tried to turn their flank, and, if they did so, to charge them before they wheeled completely round, and so take them in flank themselves.

A similar force was arranged on the left of the second line for the same purpose. The Thracian infantry of Sitalces were placed there, and Coeranus’ regiment of the cavalry of the Greek allies, and Agathon’s troops of the Odrysian irregular horse. The extreme left of the second line in this quarter was held by Andromachus’ cavalry. A division of Thracian infantry was left in guard of the camp. In advance of the right wing and centre was scattered a number of light-armed troops, of javelin-men and bowmen, with the intention of warding off the charge of the armed chariots.

[Kleber’s arrangement of his troops at the battle of Heliopolis, where, with ten thousand Europeans, he had to encounter eighty thousand Asiatics in an open plain, is worth comparing with Alexander’s tactics at Arbela. See Thiers’ Histoire du Consulat.]

Conspicuous by the brilliancy of his armor, and by the chosen band of officers who were round his person, Alexander took his own station, as his custom was, in the right wing, at the head of his cavalry; and when all the arrangements for the battle were complete, and his generals were fully instructed how to act in each probable emergency, he began to lead his men toward the enemy.

It was ever his custom to expose his life freely in battle, and to emulate the personal prowess of his great ancestor, Achilles. Perhaps, in the bold enterprise of conquering Persia, it was politic for Alexander to raise his army’s daring to the utmost by the example of his own heroic valor; and, in his subsequent campaigns, the love of the excitement, of “the raptures of the strife,” may have made him, like Murat, continue from choice a custom which he commenced from duty. But he never suffered the ardor of the soldier to make him lose the coolness of the general.

Great reliance had been placed by the Persian King on the effects of the scythe-bearing chariots. It was designed to launch these against the Macedonian phalanx, and to follow them up by a heavy charge of cavalry, which, it was hoped, would find the ranks of the spearmen disordered by the rush of the chariots, and easily destroy this most formidable part of Alexander’s force. In front, therefore, of the Persian center, where Darius took his station, and which it was supposed that the phalanx would attack, the ground had been carefully levelled and smoothed, so as to allow the chariots to charge over it with their full sweep and speed.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.