This series has seven easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: The Vicar of Christ.

Introduction

A central theme of the Medieval Centuries was the conflicts between The Holy Roman Empire and The Papacy. Innocent III Pope Lifted the Papal power to its zenith. For the rest of the medieval centuries the Papacy declined in both power and prestige. Then the modern centuries began and with them The Reformation. Papal influence and prestige would grow as The Catholic Church expanded around the world but power would not. In the nineteenth century the Popes lost their core territory in Italy and were reduced to a strictly spiritual institution. With the loss of worldly power came an increase is spiritual prestige.

Now as to the situation that the new Pope Innocent III inherited.

While the imperial power was making head against the papal authority, Italy was overrun in parts by German subjects of the emperors, and in two expeditions (1194 and 1197) Henry VI recovered the Two Sicilies from the usurper Tancred of Lecce. In his dealings with the Sicilies Innocent therefore had to reckon with the German influence which played an important part in the new settlement of the kingdom. His triumphs in this field, as well as in his conflicts with Philip Augustus of France, Otto IV of Germany, and King John of England, and in the war which he made upon heretics, are set forth in the following article in their historical order, and the cumulative growth of his supremacy forms a subject of increasing interest to the end.

This selection is from The Empire and the Papacy, 918-1273 by Thomas F. Tout published in 1908. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Thomas F. Tout (1855-1919) was Professor of History at Owens College, Manchester who specialized in Medieval History.

Time: 1208

Place: Vatican

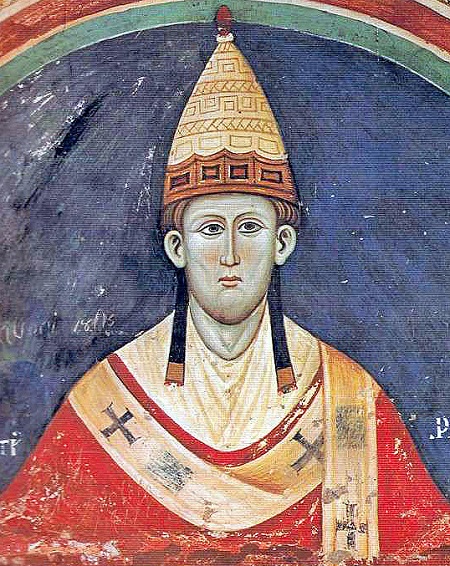

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

After the great emperors came the great Pope. Within four months of the death of Henry VI, Celestine III had been succeeded by Innocent III, under whom the visions of Gregory VII and Alexander III at last became accomplished facts, the papal authority attained its highest point of influence, and the empire, raised to such heights by Frederick Barbarossa and Henry VI, was reduced to a condition of dependence upon it.

The new Pope had been Lothaire of Segni, a member of the noble Roman house of Conti, who had studied law and theology at Paris and Bologna, and had at an early age won for himself a many-sided reputation as a jurist, a politician, and as a writer. The favor of his uncle, Clement III, had made him cardinal before he was thirty, but under Celestine III he kept in the background, disliked by the Pope, and himself suspicious of the timid and temporizing old man. But on Celestine’s death on January 8, 1198, Lothaire, though still only thirty-seven years of age, was at once hailed as his most fitting successor, as the strong man who could win for the Church all the advantages that she might hope to gain from the death of Henry VI. Nor did Innocent’s pontificate belie the promise of his early career.

Innocent III possessed a majestic and noble appearance, an unblemished private character, popular manners, a disposition prone to sudden fits of anger and melancholy, and a fierce and indomitable will. He brought to his exalted position the clearly formulated theories of the canonists as to the nature of the papal power, as well as the overweening ambition, the high courage, the keen intelligence and the perseverance and energy necessary to turn the theories of the schools into matters of every-day importance.

His enunciations of the papal doctrine put claims that Hildebrand himself had hardly ventured to advance, in the clearest and most definite light. The Pope was no mere successor of Peter, the vicegerent of man. “The Roman pontiff,” he wrote, “is the vicar, not of man, but of God himself.” “The Lord gave Peter the rule not only of the Universal Church, but also the rule of the whole world.” “The Lord Jesus Christ has set up one ruler over all things as his universal vicar, and as all things in heaven, earth, and hell bow the knee to Christ, so should all obey Christ’s vicar, that there be one flock and one shepherd.” “No king can reign rightly unless he devoutly serve Christ’s vicar.” “Princes have power in earth, priests have also power in heaven. Princes reign over the body, priests over the soul. As much as the soul is worthier than the body, so much worthier is the priesthood than the monarchy.” “The Sacerdotium is the sun, the Regnum the moon. Kings rule over their respective kingdoms, but Peter rules over the whole earth. The Sacerdotium came by divine creation, the Regnum by man’s cunning.”

In these unrestricted claims to rule over church and state alike we seem to be back again in the anarchy of the eleventh century. And it was not against the feeble feudal princes of the days of Hildebrand that Innocent III had to contend, but against strong national kings, like Philip of France and John of England. It is significant of the change of the times, that Innocent sees his chief antagonist, not so much in the empire as in the limited localized power of the national kings. When Richard of England had yielded before Henry VI, the national state gave way before the universal authority of the lord of the world. But Innocent claimed that he alone was lord of the world. The empire was but a German or Italian kingdom, ruling over its limited sphere. Only in the papacy was the old Roman tradition of universal monarchy rightly upheld.

Filled with these ambitions of universal monarchy, Innocent’s survey took in both the smallest and the greatest of European affairs. Primarily his work was that of an ecclesiastical statesman, and intrenched far upon the authority of the State. We shall see him restoring the papal authority in Rome and in the Patrimony,[53] building up the machinery of papal absolutism, protecting the infant King of Sicily, cherishing the municipal freedom of Italy, making and unmaking kings and emperors at his will, forcing the fiercest of the western sovereigns to acknowledge his feudal supremacy, and the greatest of the kings of France to reform his private life at his commands, giving his orders to the petty monarchs of Spain and Hungary, and promulgating the law of the Church Universal before the assembled prelates of Christendom in the Lateran Council.

Nevertheless, the many-sided Pontiff had not less near to his heart the spiritual and intellectual than the political direction of the universe. He had the utmost zeal for the extension of the kingdom of Christ. The affair of the crusade was, as we shall see, ever his most pressing care, and it was his bitterest grief that all his efforts to rouse the Christian world for the recovery of Jerusalem fell on deaf ears. He was strenuous in upholding orthodoxy against the daring heretics of Southern France. He was sympathetic and considerate to great religious teachers, like Francis and Dominic, from whose work he had the wisdom to anticipate the revival of the inner life of the Church. As many-sided as strong, and successful as he was strong, Innocent III represents it worthily and adequately.

Even before Innocent had attained the chair of Peter, the worst dangers that had so long beset the successors of Alexander III were over. After the death of Henry VI, the Sicilian and the German crowns were separated, and the strong anti-imperial reaction that burst out all over Italy against the oppressive ministers of Henry VI was allowed to run its full course. The danger was not so much of despotism as of anarchy, and Innocent, like Hildebrand, knew how to turn confusion to the advantage of hierarchy.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.