Albert’s daughter Agnes, Queen of Hungary appears to have been seized with a perfectly demoniacal mania for blood and revenge.

Continuing First Swiss Struggle for Liberty,

our selection from The Model Republic; a History of the Rise and Progress of the Swiss People by F. Grenfell Baker published in 1805. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in First Swiss Struggle for Liberty.

Time: 1308

Place: Switzerland

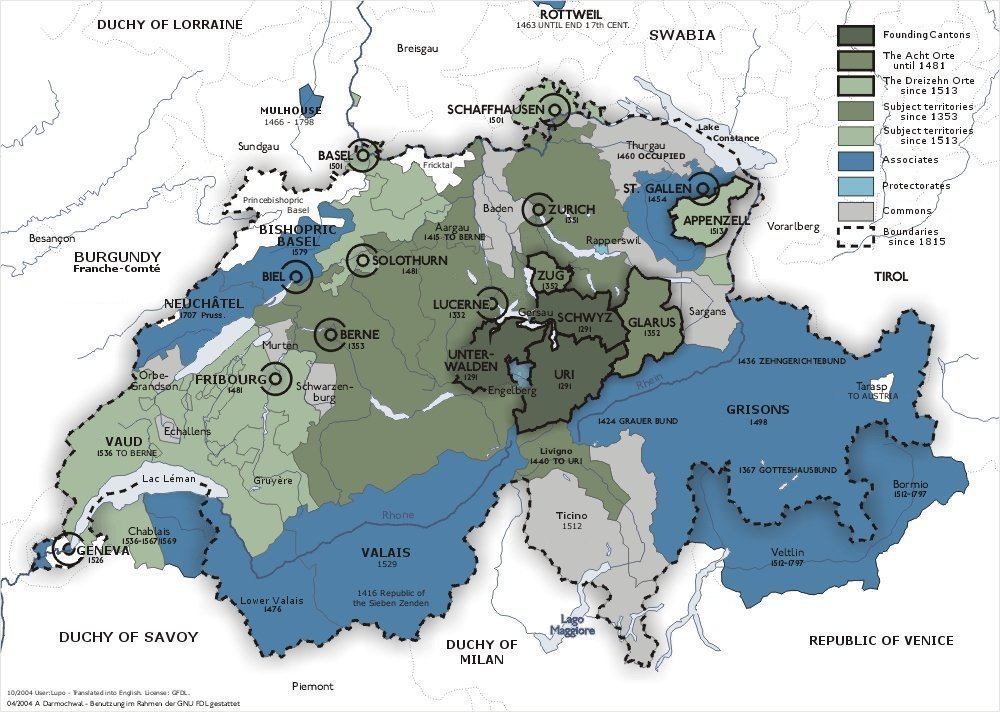

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia

In spite of this quarrel Albert allowed John and four of his fastest friends to occupy a place in his suite when he left Baden to visit his consort. Albert’s disregard of his nephew’s resentment was further shown when the party arrived on the bank of the Reuss, as he allowed him, with his friends, to accompany him in the boat in which he crossed the river. The passage was made in safety, but just as the Emperor was stepping on shore near the town of Windisch, John and three of his companions struck him down with their swords, and after inflicting a number of severe wounds left him for dead. The unhappy monarch expired a few minutes after in the arms of a passing peasant woman. All this bloody scene took place in full view of the Emperor’s train on the opposite side of the river, though no one apparently was able to render him assistance, probably from the absence of boats and the suddenness of the tragedy. The murderers succeeded in making good their escape, though two of them were afterward captured and executed, as were also a number of innocent people believed to be participators in the conspiracy. John himself was more fortunate, for, disguised as a monk, he managed for many years to hide his identity, and, after wandering in Tuscany unsuspected, eventually died in a monastery at Pisa.

Albert’s daughter Agnes, Queen of Hungary, “a woman unacquainted with the milder feelings of piety, but addicted to a certain sort of devotional habits and practices by no means inconsistent with implacable vindictiveness,” fearfully avenged his murder. This woman appears to have been seized with a perfectly demoniacal mania for blood and revenge. Aided by those in authority, who feared lest a widespread conspiracy had been formed, she seized, on the slightest suspicion, hundreds of innocent victims and put them to death with all the ferocity of a famished beast. Members of nearly a hundred noble families, and at least a thousand persons of lower rank, of every age and of both sexes, fell beneath her savage vengeance. She is said to have further whetted her appetite for horrors by wading, at Fahrwangen, in the blood of sixty-three innocent knights, exclaiming the while, “This day we bathe in May-dew.” But at last, after several months, even the implacable bloodthirstiness of the Hungarian Queen was satisfied, and the massacre ceased. Over the spot where Albert met his death Agnes built a monastery; she named it Koenigsfelden and enriched it with the spoils of her victims. Here she took up her abode for the remainder of her life, and for nearly fifty years practiced the most rigid asceticism, and here, by the side of her parents, she was eventually buried. Koenigsfelden stood on the road from Basel to Baden and Zurich, and within sight of the castle of Hapsburg, the cradle of the house of Austria.

Strenuous efforts were made by Albert’s widow to obtain the succession to the imperial throne for her son, Frederick, Duke of Austria, but the choice of the prince-electors, headed by the Archbishop of Mainz, fell on Count Henry of Luxemburg, a liberal-minded and generous noble, who was accordingly crowned, under the title of Henry VII. During the short reign of this monarch he proved himself a wise and generous friend to the Swiss, whose privileges he confirmed. He made no effort to reimpose local governors on the people of the Waldstaette, but, on the contrary, confirmed the charters of Schwyz and Uri, granted one to Unterwalden, and acknowledged jurisdiction. After Henry’s death, in 1313, civil war once more divided the empire through the rival contentions of Ludwig (Louis) of Bavaria and Albert’s son, Frederick of Austria. In this contest the powerful monastery of Einsiedeln sided with the Austrian candidate, and through its influence induced the Bishop of Constance to place the large portion of Switzerland supporting the Bavarian cause under a sentence of excommunication.

Between Einsiedeln and the Waldstaette there had long existed a feeling of bitter hostility, the canons resenting the independent spirit displayed by the peasants, and the latter remembering the many acts of arbitrary oppression they and their ancestors had suffered at the instance of the abbey. Indeed, actual hostilities were only prevented by the friendly, though interested, mediation of the citizens of Zurich, who were most anxious to preserve tranquillity in the territories of both, in order to allow their trade with Italy over the St. Gothard being carried on. They also favored peace, because since the Hapsburgs had refused permission to the peasants to enter Lucerne, these had been in the habit of bringing their cattle and dairy produce through Einsiedeln to the monks of Zurich. The action of the monks, however, in bringing about the serious sentence of excommunication so roused the spirit of the mountaineers that, headed by their Landammann, Werner Stauffacher, they attacked and captured the abbey, ransacked the whole building from cellar to altar, and carried off the monks captive to the town of Schwyz. This daring and sacrilegious act led Frederick — the hereditary avoyer of the abbey — to place the Waldstaette under the further punishment of the “ban of the empire.” Both these sentences were alike fruitless in bringing the peasants to submission to the house of Austria. Shortly after, on Ludwig ascending the throne, the “ban” was removed by the new monarch, and, with the aid of the Archbishop of Mainz, the Metropolitan of Constance in 1315, the excommunication was also revoked.

The triumph of Ludwig’s claims over those of Frederick began that long series of deadly conflicts between the Swiss and the house of Austria that led the two nations for so many years to regard each other as natural and implacable enemies. At this time Austria was governed by Duke Leopold, a man of arrogant, passionate temper, of unscrupulous ambition, and brutal cruelty, according to the Swiss chronicles, but who, from other accounts, does not appear specially to have deserved this character. His hatred of the Swiss was greatly increased by their action in opposing his brother, Frederick, in the late contest. No sooner, indeed, were the troubles of that contest over than he prepared to wreak his vengeance, and once for all crush the power and independence of the Forest States, and, as he declared, “trample the audacious rustics under his feet.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.