Today’s installment concludes First Swiss Struggle for Liberty,

our selection from The Model Republic; a History of the Rise and Progress of the Swiss People by F. Grenfell Baker published in 1805. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in First Swiss Struggle for Liberty.

Time: 1308

Place: Switzerland

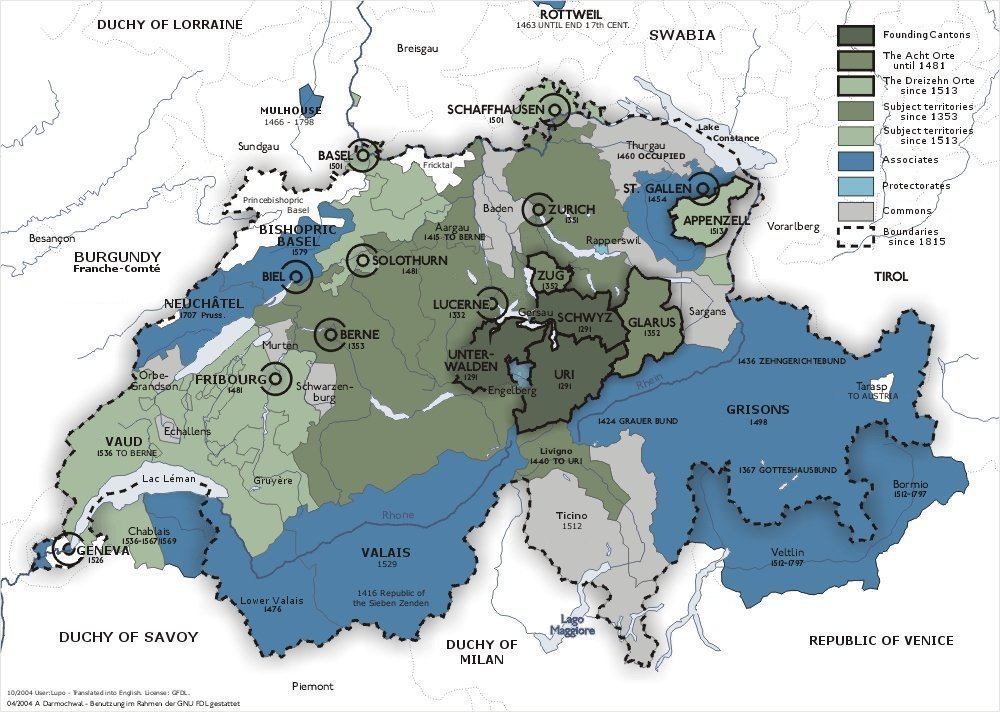

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia

Rapidly collecting his forces, Leopold soon found himself at the head of fifteen thousand or twenty thousand well-armed men, including a large body of heavily equipped cavalry. These latter were then looked upon as the main strength of an army. Most of the ancient nobility of Hapsburg, Kyburg, and Lenzburg rallied to his banners, besides many of the lesser nobles and a contingent from Zurich, the citizens of which, deserting their natural allies, had formed a treaty with Austria. Against this formidable array the men of Schwyz, Uri, and Unterwalden were only able to muster some fourteen hundred men, who, however, made up for their want of weapons and discipline by the geographical advantages of the country, by their patriotism, unity, and determined bravery.

Nothing now seemed to intervene between the Swiss and imminent destruction, when, viewing with a compassion, most rare in those days, the impending fate of the heroic mountaineers, the powerful Count of Toggenborg tried to negotiate a peace with the Duke. Leopold’s terms, however, were so humiliating and evidently so insincere that nothing came of these proposals.

On November 3, 1315, Leopold’s army reached Baden, where a council was held to determine upon the details of the campaign, a campaign having for its object, as the Duke openly declared, “the extirpation of the whole race of the people of Waldstaette.” The difficulties of the enterprise now began to show themselves, as several of Leopold’s followers, being well acquainted with the nature of the country and the characters of the inhabitants, pointed out that both would offer a determined resistance. Finally, relying upon their numbers and superior arms, it was settled to march on Schwyz, through the Sattel Pass by Morgarten, making Zug the base of operations; and while a false attack should be threatened on the side of Arth, Unterwalden should be attacked from Lucerne, as well as by a large force under the Count of Strasburg by way of the Bruenig. Leopold himself was to lead the main army and enter Schwyz through the pass. Had these operations remained secret, or been carried out successfully, the course of Swiss history would probably have been very different from what it was; but fortunately for the cause of freedom, the Austrian plans became known in time, and failed signally when put to the test. According to ancient chronicles, as the Confederates were hurrying to repel the feint from Arth, a friendly Austrian baron, named Henry of Huenenberg, shot an arrow amid them bearing the message, “Guard Morgarten on the eve of St. Othmar.” Be this as it may, the Swiss collected their little band on the Sattel, between which mountain and the eastern shore of the Lake of Egeri is situated the ever-memorable Pass of Morgarten. Here, on the night of November 14th, they collected a number of loose bowlders and tree-trunks, and then, having offered up prayers for the preservation of their country, they awaited with resolution the coming struggle.

With the first dawn of morning the Austrian army — the first that ever entered the country — made its appearance in the pass, headed by Duke Leopold and his formidable cavalry. Suddenly, when the whole narrow defile was blocked with horse and foot, thousands of heavy stones and trees were hurled among them from the neighboring heights, where the peasant band, forming the Swiss force, lay concealed. The suddenness and vigor of this unexpected attack quickly threw the first ranks of the invaders into confusion, and caused a panic to seize the horses, many of which in their fright turned and trampled down the men behind. Rapidly the panic increased as the showers of missiles came tearing down, and soon the whole army was in a state of wild terror and confusion — a condition greatly assisted by the slippery nature of the ground. Then, with wild shouts, and brandishing their iron-studded clubs and their formidable halberts and scythes, down the mountain-side rushed, with the fury of their native avalanche, the heroic Confederates; and falling on their foes literally slew them by thousands. Many hundreds of the Austrians perished in the lake, the men of Zurich alone making a stand, and falling each where he fought. Few succeeded in effecting their escape from what was little less than a general butchery.

On that memorable day all the flower of Austria’s nobility lay dead within the country they had hoped so easily to conquer. The Duke, with a handful of followers, alone survived, and even these were forced to undergo many perils before they eventually arrived in safety at Winterthur. Neither were the other attacks, under the Count of Strasburg and the forces from Lucerne, more successful for the invaders. Both armies were repulsed with enormous loss by the men of Unterwalden, who gave no quarter, many of their opponents being their own countrymen from the estates of the abbey of Interlaken. After these signal victories the Swiss, according to ancient custom, offered up a solemn thanksgiving to almighty God for their success and the overthrow of their enemies; and then, having laden themselves with the spoils of the dead, they returned to their humble occupations, whence the defense of their country and their lives had called them away. Among the Swiss, Morgarten has always taken the first place in the long record of heroic victories that since 1315 has made the fame of Swiss arms second to none in Europe. This victory at once brought the Waldstaette out of their long obscurity, and placed them in the front rank as powerful and respected states in Switzerland.

Leopold, on his return to Austria, was so satisfied with the ability of the “audacious rustics” to defend themselves that he made no further attempt to enter their country.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on First Swiss Struggle for Liberty by F. Grenfell Baker from his book The Model Republic; a History of the Rise and Progress of the Swiss People published in 1805. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on First Swiss Struggle for Liberty here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.