“Do not, my lord,” said Frederick, “talk to me of magnanimity; a prince ought first to consult his own interests.”

Continuing Prussia Invades Silesia,

our selection from Lectures on Modern History by William Smyth published in 1840. The selection is presented in three easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Prussia Invades Silesia.

Time: 1740

Place: Silesia

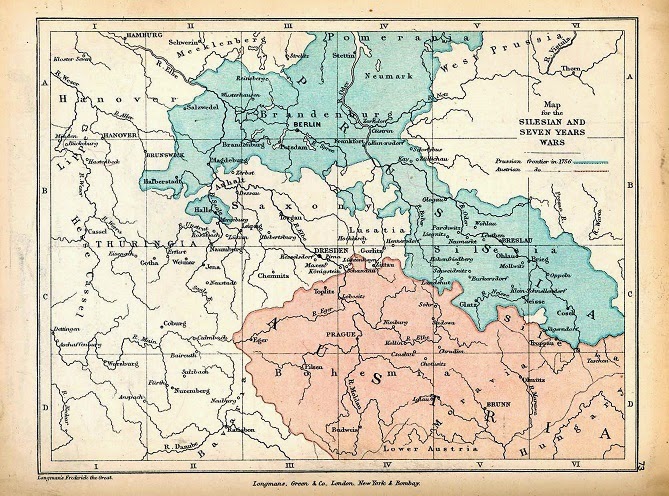

The feelings of the young Queen may be easily imagined, powerful in the qualities of her understanding, with all the high sensibilities which are often united to a commanding mind, and educated in all the lofty notions which have so uniformly characterized her illustrious house. She resisted; but her arms proved in the event unsuccessful. She was not prepared; and even if she had been, the combination was too wide and powerful against her. According to the plan of her enemies, more particularly of France (her greatest enemy), Bohemia and Upper Austria, spite of all her efforts, were likely to be assigned to the Elector of Bavaria; Moravia and Upper Silesia to the Elector of Saxony; Lower Silesia and the country of Glatz to the King of Prussia; Austria and Lombardy to Spain; and some compensation to be allotted to the King of Sardinia.

It was therefore, at last, necessary to detach the King of Prussia from the general combination by some important sacrifice. The sufferings, the agonies, of the poor Queen were extreme. Lord Hyndford, on the part of England as a mediating power, prevailed on the helpless Maria Theresa to abate something of her lofty spirit, and make some offers to the King. “At the beginning of the war,” said Frederick, “I might have been contented with this proposal, but not now. Shall I again give the Austrians battle, and drive them out of Silesia? You will then see that I shall receive other proposals. At present I must have four duchies, and not one. Do not, my lord,” said the King, “talk to me of magnanimity; a prince ought first to consult his own interests. I am not averse to peace; but I expect to have four duchies, and will have them.”

At a subsequent period the same scene was to be renewed, and Mr. Robinson, the English ambassador, who was very naturally captivated with the attractions and spirit of Maria Theresa, endeavored to rouse her to a sense of her danger. “Not only for political reasons,” replied the Queen, “but from conscience and honor, I will not consent to part with much in Silesia. No sooner is one enemy satisfied than another starts up; another, and then another, must be contented, and all at my expense.” “You must yield to the hard necessity of the times,” said Mr. Robinson. “What would I not give, except in Silesia?” replied the impatient Queen. “Let him take all we have in Gelderland; and if he is not to be gained by that sacrifice, others may. Let the King, your master, only speak to the Elector of Bavaria! Oh, the King, your master–let him only march! let him march only!”

But England could not be prevailed upon to declare war. The dangers of Maria Theresa became more and more imminent, and a consent to further offers was extorted from her. “I am afraid,” said Mr. Robinson, “some of these proposals will be rejected by the King.” “I wish he may reject them,” said the Queen. “Save Limburg, if possible, were it only for the quiet of my conscience. God knows how I shall answer for the cession, having sworn to the states of Brabant never to alienate any part of their country.”

Mr. Robinson, who was an enthusiast in the cause of the Queen, is understood to have made some idle experiment of his own eloquence on the King of Prussia; to have pleaded her cause in their next interview; to have spoken, not as if he was addressing a cold-hearted, bad man, but as if speaking in the House of Commons of his own country, in the assembly of a free people, with generosity in their feelings and uprightness and honor in their hearts. The King, in all the malignant security of triumphant power, in all the composed consciousness of great intellectual talents, affected to return him eloquence for eloquence; said his ancestors would rise out of their tombs to reproach him if he abandoned the rights that had been transmitted to him; that he could not live with reputation if he lightly abandoned an enterprise which had been the first act of his reign; that he would sooner be crushed with his whole army, etc. And then, descending from his oratorical elevation, declared that he would _now_ “not only have the four duchies, but all Lower Silesia, with the town of Breslau. If the Queen does not satisfy me in six weeks, I will have four duchies more. They who want peace will give me what I want. I am sick of ultimatums; I will hear no more of them. My part is taken; I again repeat my demand of all Lower Silesia. This is my final answer, and I will give no other.” He then abruptly broke off the conference, and left Mr. Robinson to his own reflections.

The situation of the young Queen now became truly deplorable. The King of Prussia was making himself the entire master of Silesia; two French armies poured over the countries of Germany; the Elector of Bavaria, joined by one of them, had pushed a body of troops within eight miles of Vienna, and the capital had been summoned to surrender. The King of Sardinia threatened hostilities; so did the Spanish army. The Electors of Saxony, Cologne, and Palatine joined the grand confederacy; and abandoned by all her allies but Great Britain, without treasure, without an army, and without ministers, she appealed, or rather fled for refuge and compassion, to her subjects in Hungary.

These subjects she had at her accession conciliated by taking the oath which had been abolished by her ancestor Leopold, the confirmation of their just rights, privileges, and approved customs. She had taken this oath at her accession, and she was now to reap the benefit of that sense of justice and real magnanimity which she had displayed, and which, it may fairly be pronounced, sovereigns and governments will always find it their interest, as well as their duty, to display, while the human heart is constituted, as it has always been, proud and eager to acknowledge with gratitude and affection the slightest condescensions of kings and princes, the slightest marks of attention and benevolence in those who are illustrious by their birth or elevated by their situation.

When Maria Theresa had first proposed to repair to these subjects, a suitor for their protection, the gray-headed politicians of her court had, it seems, assured her that she could not possibly succeed; that the Hungarians, when the Pragmatic Sanction had been proposed to them by her father, had declared that they were accustomed to be governed only by men; and that they would seize the opportunity of withdrawing from her rule, and from their allegiance to the house of Austria.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.