This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Frederick the Great Versus Maria Theresa.

Introduction

When Maria Theresa inherited the Hapsburg throne, Frederick the King of Prussia attacked. His only reason was that she was a woman. This act set the mindset of German militarism for centuries until the end of the Nazi era in 1945.

This selection is from Lectures on Modern History by William Smyth published in 1840. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

William Smyth was a professor of modern history at Cambridge University from 1807 to 1847. He published a collection of his lectures from which this selection is from.

Time: 1740

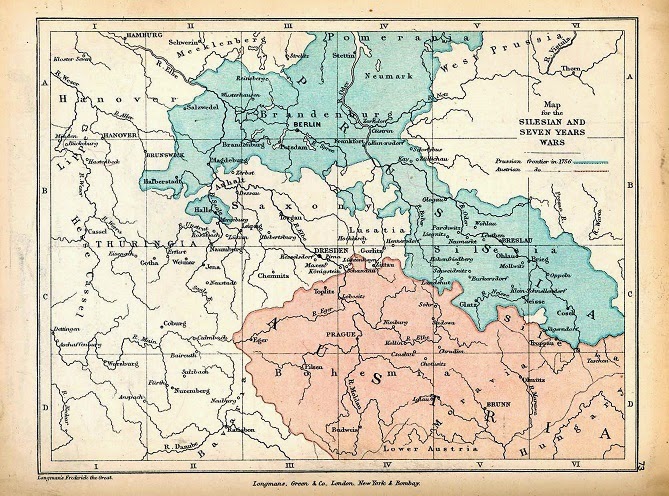

Place: Silesia

In 1740 Maria Theresa ascends the throne of her ancestors–possessed, it seems, of a commanding figure, great beauty, animation and sweetness of countenance, a pleasing tone of voice, fascinating manners, and uniting feminine grace with a strength of understanding and an intrepidity above her sex. But her treasury contained only one hundred thousand florins, and these claimed by the Empress Dowager; her army, exclusive of the troops in Italy and the Low Countries, did not amount to thirty thousand effective men; a scarcity of provisions and great discontent existed in the capital; rumors were circulated that the government was dissolved, that the Elector of Brunswick was hourly expected to take possession of the Austrian territories; apprehensions were entertained of the distant provinces–that the Hungarians, supported by the Turks, might revive the elective monarchy; different claimants on the Austrian succession were expected to arise; besides, the Elector of Bavaria, the Elector of Cologne, and the Elector Palatine were evidently hostile; the ministers themselves, while the Queen was herself without experience or knowledge of business, were timorous, desponding, irresolute, or worn out with age. To these ministers, says Mr. Robinson, in his dispatches to the English court, “the Turks seemed already in Hungary, the Hungarians themselves in arms, the Saxons in Bohemia, the Bavarians at the gates of Vienna, and France the soul of the whole.” The Elector of Bavaria, indeed, did not conceal his claims to the kingdom of Bohemia and the Austrian dominions; and, finally, while the Queen had scarcely taken possession of her throne, a new claimant appeared in the person of Frederick of Prussia, who acted with “such consummate address and secrecy”–as it is called by the historian–that is, with such unprincipled hypocrisy and cunning, that his designs were scarcely even suspected when his troops entered the Austrian dominions.

Silesia was the province which he resolved, in the present helpless situation of the young Queen, to wrest from the house of Austria. He revived some antiquated claims on parts of that duchy. The ancestors of Maria Theresa had not behaved handsomely to the ancestors of Frederick, and the young Queen was now to become a lesson to all princes and states of the real wisdom that always belongs to the honorable and scrupulous performance of all public engagements. Little or nothing, however, can be urged in favor of Frederick. Prescription must be allowed at length to justify possession in cases not very flagrant. The world cannot be perpetually disturbed by the squabbles and collisions of its rulers; and the justice of his cause was, indeed, as is evident from all the circumstances of the case, and his own writings, the last and the least of all the many futile reasons which he alleged for the invasion of the possessions of Maria Theresa, the heiress of the Austrian dominions, young, beautiful, and unoffending, but inexperienced and unprotected.

The common robber has sometimes the excuse of want; banditti, in a disorderly country, may pillage, and, when resisted, murder; but the crimes of men, even atrocious as these, are confined at least to a contracted space, and their consequences extend not beyond a limited period. It was not so with Frederick. The outrages of his ambition were to be followed up by an immediate war. He could never suppose that, even if he succeeded in getting possession of Silesia, the house of Austria could ever forget the insult and the injury that had thus been received; he could never suppose, though Maria Theresa might have no protection from his cruelty and injustice, that this illustrious house would never again have the power, in some way or other, to avenge their wrongs. One war, therefore, even if successful, was not to be the only consequence; succeeding wars were to be expected; long and inveterate jealousy and hatred were to follow; and he and his subjects were, for a long succession of years, to be put to the necessity of defending, by unnatural exertions, what had been acquired–if acquired–by his own unprincipled ferocity. Such were the consequences that were fairly to be expected. What, in fact, took place?

The seizure of this province of Silesia was first supported by a war, then by a revival of it, then by the dreadful Seven Years’ War. Near a million of men perished on the one side and on the other. Every measure and movement of the King’s administration flowed as a direct consequence from this original aggression: his military system, the necessity of rendering his kingdom one of the first-rate powers of Europe, and, in short, all the long train of his faults, his tyrannies, and his crimes. We will cast a momentary glance on the opening scenes of this contest between the two houses.

As a preparatory step to his invasion of Silesia, the King sent a message to the Austrian court. “I am come,” said the Prussian envoy to the husband of Maria Theresa, “with safety for the house of Austria in one hand, and the imperial crown for your royal highness in the other. The troops and money of my master are at the service of the Queen, and cannot fail of being acceptable at a time when she is in want of both, and can only depend on so considerable a prince as the King of Prussia and his allies, the maritime powers, and Russia. As the King, my master, from the situation of his dominions, will be exposed to great danger from this alliance, it is hoped that, as an indemnification, the Queen of Hungary will not offer him less than the whole duchy of Silesia.” “Nobody,” he added, “is more firm in his resolutions than the King of Prussia: he must and will enter Silesia; once entered, he must and will proceed; and if not secured by the immediate cession of that province, his troops and money will be offered to the electors of Saxony and Bavaria.” Such were the King’s notifications to Maria Theresa. Soon after, in a letter to the same Duke of Lorraine, the husband of Maria Theresa, “My heart,” says Frederick–for he wrote as if he conceived he had one–“My heart,” says Frederick, “has no share in the mischief which my hand is doing to your court.”

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.