To the cold and relentless ambition of Frederick, to a prince whose heart had withered at thirty, an appeal like this had been made in vain.

Today’s installment concludes Prussia Invades Silesia,

our selection from Lectures on Modern History by William Smyth published in 1840. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Prussia Invades Silesia.

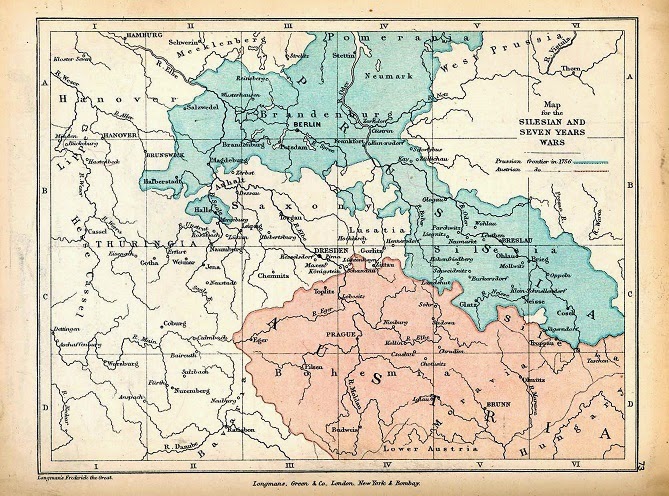

Time: 1740

Place: Silesia

Maria Theresa, young and generous and high-spirited herself, had confidence in human virtue. She repaired to Hungary; she summoned the states of the Diet; she entered the hall, clad in deep mourning; habited herself in the Hungarian dress; placed the crown of St. Stephen on her head, the cimeter at her side; showed her subjects that she could herself cherish and venerate whatever was dear and venerable in their sight; separated not herself in her sympathies and opinions from those whose sympathies and opinions she was to awaken and direct, traversed the apartment with a slow and majestic step, ascended the tribune whence the sovereigns had been accustomed to harangue the states, committed to her chancellor the detail of her distressed situation, and then herself addressed them in the language which was familiar to them, the immortal language of Rome, which was not now for the first time to be employed against the enterprises of injustice and the wrongs of the oppressor.

To the cold and relentless ambition of Frederick, to a prince whose heart had withered at thirty, an appeal like this had been made in vain; but not so to the freeborn warriors, who saw no possessions to be coveted like the conscious enjoyment of honorable and generous feelings–no fame, no glory like the character of the protectors of the helpless and the avengers of the innocent. Youth, beauty, and distress obtained that triumph, which, for the honor of the one sex, it is to be hoped will never be denied to the merits and afflictions of the other. A thousand swords leaped from their scabbards and attested the unbought generosity and courage of untutored nature. “_Moriamur pro rege nostro_, Maria Theresa!” was the voice that resounded through the hall (“We will die for our sovereign, Maria Theresa!”). The Queen, who had hitherto preserved a calm and dignified deportment, burst into tears—I tell but the facts of history. Tears started to the eyes of Maria Theresa, when standing before her heroic defenders–those tears which no misfortunes, no suffering, would have drawn from her in the presence of her enemies and oppressors. “Moriamur pro rege nostro, Maria Theresa!” was again and again heard. The voice, the shout, the acclamation that reëchoed around her, and enthusiasm and frenzy in her cause, were the necessary effect of this union of every dignified sensibility which the heart can acknowledge and the understanding honor.

It is not always that in history we can pursue the train of events, and find our moral feelings gratified as we proceed; but in general we may. Philip II overpowered not the Low Countries, nor Louis, Holland; and even on this occasion of the distress and danger of Maria Theresa we may find an important, though not a perfect and complete, triumph. The resolutions of the Hungarian Diet were supported by the nation; Croats, Pandours, Slavonians, flocked to the royal standard, and they struck terror into the disciplined armies of Germany and France. The genius of the great General Kevenhuller was called into action by the Queen; Vienna was put into a state of defense; divisions began to rise among the Queen’s enemies; a sacrifice was at last made to Frederick–he was bought off by the cession of Lower Silesia and Breslau; and the Queen and her generals, thus obtaining a respite from this able and enterprising robber, were enabled to direct, and successfully direct, their efforts against the remaining hosts of plunderers that had assailed her. France, that with perfidy and atrocity had summoned every surrounding power to the destruction of the house of Austria, in the moment of the helplessness and inexperience of the new sovereign—France was at least, if Frederick was not, defeated, disappointed, and disgraced.

The interest that belongs to a character like that of Maria Theresa, of strong feelings and great abilities, never leaves the narrative, of which she is the heroine. The student cannot expect that he should always approve the conduct or the sentiments that but too naturally flowed from qualities like these, when found in a princess like Maria Theresa–a princess placed in situations so fitted to betray her into violence and even rancor–a princess who had been a first-rate sovereign of Europe at four-and-twenty, and who had never been admitted to that moral discipline to which ordinary mortals, who act in the presence of their equals, are so happily subjected. That the loss of Silesia should never be forgotten–the King of Prussia never forgiven–that his total destruction would have been the highest gratification to her, cannot be objects of surprise. The mixed character of human nature seldom affords, when all its propensities are drawn out by circumstances, any proper theme for the entire and unqualified praises of a moralist; but everything is pardoned to Maria Theresa, when she is compared, as she must constantly be, with her great rival, Frederick. Errors and faults we can overlook when they are those of our common nature; intractability, impetuosity, lofty pride, superstition, even bigotry, an impatience of wrongs, furious and implacable–all these, the faults of Maria Theresa, may be forgiven, may at least be understood. But Frederick had no merits save courage and ability; these, great as they are, cannot reconcile us to a character with which we can have no sympathy–of which the beginning, the middle, and the end, the foundation and the essence, were entire, unceasing, inextinguishable, concentrated selfishness.

I do not detain my hearers with any further reference to Maria Theresa. She long occupies the pages of history–the interesting and captivating princess–the able and still attractive Queen–the respected and venerable matron, grown prudent by long familiarity with the uncertainty of fortune, and sinking into decline amid the praises and blessings of her subjects.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Prussia Invades Silesia by William Smyth from his book Lectures on Modern History published in 1840. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.