Young Bach had received no great instruction in the schools of composition.

Continuing Bach Lays the Foundation of Modern Music,

our selection from The Growth and Influence of Music in Relation to Civilization by Henry Tipper published in 1898. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Bach Lays the Foundation of Modern Music.

Time: 1703 – 1750

Place: Germany

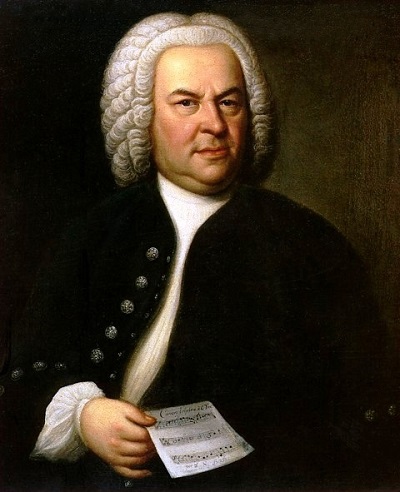

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Again, the traditions of the great reformer must have been imbibed by Sebastian Bach from infancy. Surrounding his native town lay a circle of wooded heights, from one of which arose the Wartburg, that illustrious shrine of the German nation whither in medieval and modern times her sons have repaired to exhibit and replenish their lamp of genius. There the minnesingers had gathered in contest a song; thither as a modern Elijah came the great monk, weary of soul, yet whose immortal genius unfolded the page of Sacred Writ; and down the wood-clad slope came issuing the melody of the Hebrew psalmist, translated into German speech and entering into German hearts, mingled with the narrative of the Redeemer’s passion lit by awful and solemn glory of Eternal Love. Who shall say that young Bach knew not of these things? Who will contend that, when his genius matured and ripened, the immortal tones in which the eternal passion was portrayed owed nothing to this sympathy of association, this spiritual life with the great reformer born two centuries before?

Yet once more. The Bach family was full of affection and sympathy one toward the other. Each year witnessed a reunion of the various members of the family scattered throughout Thuringia, and each came bearing the gift of music. As a child among the elders we can imagine how the young Sebastian revered his uncles, Johann Christopher and Michael Sebastian, in whom were conserved and developed the Lutheran tonal principles and traditions; how he somewhat feared the austere character of his elder brother, Johann Christopher, to whose charge he was entrusted upon the death of his father.

But we need not imagine how the soul of the young boy was filled with inexpressible yearning for the art of music. We know that it was so. His brother, who instructed him, gauged not the nature of the lad. Often and often did the boy’s wistful eyes and loving heart covet the possession of a manuscript book kept by his brother in strict reserve, containing a priceless collection of compositions by the great German masters and mediators. The boy extracted them from their resting-place, and we see the young tone-prophet striving to master the art-forms of Reinken, Buxtehude, Frescobaldi, Kerl, Froberger, and Pachelbel, endeavoring to wrest from them their style and inmost meaning by the light of the moon’s pale rays, which led, alas! in after-years to blindness.

What revelations came to the soul of the young musician we know not. But his genius thus directed knew no pause until it had won forever the freedom of the tonal art, until the last fetter of conventionality had been removed, until in all dignity and beauty music came forth, henceforth to comfort and solace the human heart. But of this anon. We trace the young boy to school; we see him a chorister in the choir of St. Michael’s, Lueneburg. Here he entered the gymnasium, studying Greek and Latin, organ-and violin-playing. Here, too, he exhausted the treasures of the musical library. But at Hamburg the great Reinken was giving a series of organ recitals. Thither young Bach repaired. At Celle he became acquainted with several suites and other compositions of celebrated French masters. In 1703 he became violinist in the Saxe-Weimar orchestra, and in the same year, aged eighteen, he was appointed organist at the new church at Arnstadt, where other members of his family had held similar positions. Thus already we have ample evidence both of intense activity and catholicity of taste, and now, a mere youth, he enters upon his life-work: the perfecting of church music, especially the chorale form, and the emancipation of the art from any influence whatsoever other than derives from contact with nature and emotion. If we ask what equipment he had for his task, we answer: enthusiasm, so deep, so tempered in all its qualities, that, though in a few years he became the ablest performer of his time upon the harpsichord and organ, yet never once is the term “virtuoso” associated in our thought with the purity of aspiration which characterized him. His enthusiasm was religious, deep-seated, his vision far and wide, and no temporary triumph, no sunlit cloud of fame, could satisfy the imperative needs of his inmost nature. And this nature was calm, with the calmness of strength and with that tender purity and homely virtue which characterized the surroundings of his boyhood.

This enthusiasm, this religious instinct, for what was noblest and best, led him early, as we have seen, to seek inspiration from the works of men who combined in their compositions all that the great previously existing schools had taught. Bach was never weary of learning if perchance he could attain a more lucid or more beautiful expression of his thought. We have, then, this enthusiasm, this capacity for at once discerning what was best. Add to it one more quality — the religious, in its best sense, which young Bach possessed to the uttermost, the feeling that his art was but the medium of expression for the deep things of God — and we have the equipment with which the young musician started on his quest.

Young Bach had received no great instruction in the schools of composition. That which he had he gathered with a catholicity of taste from all the renowned masters. Not one of his immediate ancestors had stirred beyond the confines of their simple home. Well for him was it so. No late meretricious Neapolitan tinsel could exist in the quiet, calm beauty of his Thuringian dwelling-place. Nature lay before him. “Come,” she said, “seek to understand me. I have treasures that ye know not of, treasures that can only be gathered by the pure in heart and patient in spirit. Here around you, in your quiet German home, are the elements of all your strength. Here there is no distraction. Riches shall not allure you. Honorable poverty shall minister to your purity”; and young Bach knew that the voice was true, and, heeding it, there came to him likewise an inner voice, relating spiritual things, even as the voice of Nature related natural things.

Comprehending, then, his character, we pass on. His work at this period was formal. He felt, but could not express. But at Lubeck the noble-hearted Buxtehude was endeavoring to bring home to the hearts of the people the mission of music. Bach went thither. Fascinated by the grand organ-playing of the Lubeck master, and listening with heart-felt love to those memorable concerts of which we have previously spoken, Bach forgot both time and engagements. When he returned to Arnstadt, the spirit of Buxtehude was upon him. Henceforth the quiet people of Arnstadt knew no rest. Variations, subtle, beautiful, a refined and fuller contrapuntal treatment, mingled with the chorale. The conservatism of Arnstadt received a severe shock — a dreadful experience, doubtless, to the quiet German town. Such genius could come to no good end, and so the consistory and Bach agreed to part.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.