Today’s installment concludes Bach Lays the Foundation of Modern Music,

our selection from The Growth and Influence of Music in Relation to Civilization by Henry Tipper published in 1898.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Bach Lays the Foundation of Modern Music.

Time: 1703 – 1750

Place: Germany

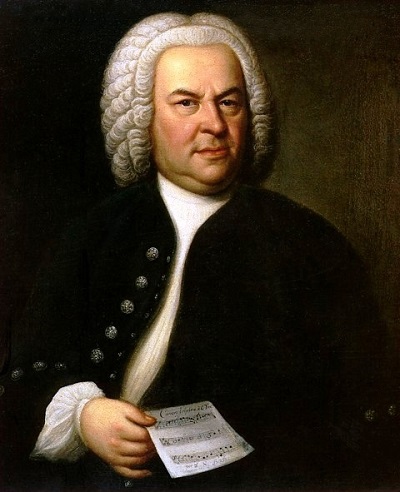

Public domain image from Wikipedia

But a new sphere of action here again opens to Bach. His master and friend, the Prince of Koethen, was distracted from the pursuit of music by his wife’s want of interest therein, and so Bach sorrowfully looks around him for a more congenial appointment. This he found at Leipsic, in 1723, as cantor to the school of St. Thomas. Leipsic, like Weimar, was celebrated for its intellectual life; but the various vexations which the great musician encountered from the action of the authorities reflects but little credit upon them. Bach’s labors here were simply Titanic. There were four churches at Leipsic, the principal being St. Nicholas and St. Thomas. Bach seems to have been responsible for the musical service at each. How innate and healthy was his genius may be inferred from the fact that for these musical services alone three hundred eighty cantatas seem to have been composed. Bach entered upon his labors at Leipzig at the age of thirty-eight, and continued therein until his death, in 1750. Let us examine briefly the nature of these labors, and endeavor to glean from them their characteristic principles.

When Bach came to Leipzig he came full of experience and power. As a youth he had devoted himself to the perfecting of church music. Untiringly, unceasingly, with steadfast love, he had brought the laws of counterpoint and fugue to mingle with the grace of melody and the genius of a noble imagination. At Koethen his poetic and artistic temperament roamed through the realms of nature, and brought us near to the understanding of their varied utterance. At Leipzig he finished the education of his life and his career as a tone-poet. He seeks again the shelter of the temple, but his genius has matured and ripened. He has examined the mysteries of life. His enthusiasm for the pure and good is stronger than ever, but life is still a mystery. Evil, pain, love deep as hell and high as heaven, the Titanic conflict of opposing principles, Nature and her decrees, sorrow, remorse, sweet, unaffected joy, and tranquil resignation — what mean they all? The answer, the solution, is on Calvary. There is no other solution. Intellect, deny it how it will, is baffled by the complex problem. The solution is of love through trouble and anguish. The Passion music of Bach rises to the sublime understanding of this grand mystery, and again the evolution of the old mystery and Passion-play consummates in a kindred mind. Again the triumph of faith is with the German. Luther frees the understanding from tyranny. Bach raises it to the region of genius and sympathy, and closes the labors of a thousand years of Christian tonal effort by his Passion music of the Redeemer. But while this is so, he initiated the modern period of tonal art, leaving, however, this Passion music as his noblest legacy, as if to warn men that no other solution of life exists.

But though Bach’s genius was thus supreme, it was not because he was undisturbed by the vexations of daily life. Rarely, if ever, has an artist equally great produced in such boundless profusion the highest works of genius, when engaged with men most frequently unable to understand his thought, and immersed in the arduous duties of teacher in an art noteworthy of producing fatigue and exhaustion of spirit. But his enthusiasm and strength were equal to the task. With grand integrity, and desire for the welfare of the congregations of the churches alluded to, he obtained from their respective ministers the texts of their discourses for the ensuing Sundays, and produced, apparently without effort, hundreds of cantatas to convey to the hearers the inner meaning of the words which fell from the preacher’s lips. These cantatas frequently opened with orchestral introduction followed by a chorus, usually very impressive, and imbued with the meaning of the text. The recitatives and solo airs would still further convey this meaning, while a chorale or hymn in four parts, with elaborate instrumental accompaniment, served to express the feelings of the whole congregation. To each instrument was assigned a separate part, and the whole accompaniment was separate from the singing.

But if Bach in the consummation of the chorale perfected Luther’s work in the realm of music, he in his Passion music finds worthy expression of a nation’s devotion. His genius, as it were, felt the spirit-life of the past. His soul vibrated to the yearnings of the unknown millions of his race who had passed away in the centuries preceding him, and whose consolation in their humble toil, in the various hardships of their lives, was the narrative of this Passion music of the Savior Christ. The rough, dramatic presentation accorded to this narrative gathered, as time went on, elements of beauty and traditional treatment around it. It was powerfully to affect the drama proper and oratorio, but in its direct and proper functions it was to inspire the first, and in some respects the greatest, of the great musicians of Germany to his utmost effort, to his most lofty flight of genius, as his winged spirit soared through the ages of the past toward the future ages yet to come.

This Passion music of St. Matthew is the noblest presentment of the characteristics of the German mind, and is unsurpassed in the realm of religious art. It is an unfolding of the German spirit, and evidences qualities the possession of which makes for national greatness.

As we have said, Bach is the great lyric poet of his nation, the first great German genius after the devastating horrors of war. Looming on the sight, or as contemporaries, are Handel, Leibnitz, Wolf, Klopstock, Lessing, and Winckelmann. The modern era, with its philosophy and revolution, has arrived. The domain of thought is enwidened, and the Middle Ages blend and fade in the historic vista of the past. But the modern era commences with these great affirmations in art and poetry. Bach takes the narrative of the Passion, and erects the Cross anew with sympathetic genius of art and love. Handel, as if he had caught Isaiah’s prophetic fire, gave to Europe its most beautiful and noble epic, the Messiah; and Klopstock, the first of the great line of Germany’s modern poets, devoted his genius and labor to the same subject. But with Bach and Handel no miserable conflicting elements of theology sully the conception of the Saviour Christ. These great artists rise to the universal and the true. The highest art is absolute and knows no appeal. It is in harmony with universal law, both spiritual and physical.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Bach Lays the Foundation of Modern Music by Henry Tipper from his book The Growth and Influence of Music in Relation to Civilization published in 1898. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Bach Lays the Foundation of Modern Music here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.