We have seen how patiently, how toilsomely, Music has broken one by one the fetters of conventionality; how she has grown in strength and beauty, anticipating the moment of her final deliverance.

Continuing Bach Lays the Foundation of Modern Music,

our selection from The Growth and Influence of Music in Relation to Civilization by Henry Tipper published in 1898. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Bach Lays the Foundation of Modern Music.

Time: 1703 – 1750

Place: Germany

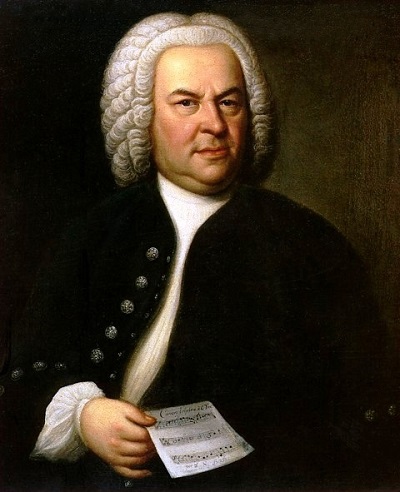

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Bach had married in October, 1707. In 1708, while at Muehlhausen, his first considerable work, composed for the municipal elector, appeared. His election at Saxe-Weimar was undoubtedly owing to his playing before the Duke Wilhelm Ernst, and we can imagine with what pleasure the young musician, conscious of great power, looked forward to the intellectual and cultured life for which Weimar was renowned. In the course of a few years Bach was appointed orchestral and concert director to the Duke.

The liberal atmosphere of Weimar, the appreciation of men whose opinion was of worth, could but stimulate the mental faculties and widen the range of thought, and there is a breadth of conception and majesty in Bach at this period unknown before. With the assiduity of genius he labored for the realization of his ideal. Palestrina, Lotti, and Caldara were laid under contribution. The master transcribed the works of these composers with his own hands, and arranged the violin concertos of Vivaldi for the harpsichord and organ. It is ever with the greatest artists. They assimulate all the forms of kindred art, yet never sacrifice their individuality. The means enabling them to express their inmost soul must be found, but their soul will alone dictate the form which its expression will assume.

But Bach is approaching the close of the first period of his career. An invitation has been given him (1717) to become conductor of the orchestra at the court of Leopold of Anhalt-Koethen, a prince remarkable for his benevolence and cultured attainments. Here his duties were comparatively slight and his leisure abundant. Hitherto he had been engaged, as it were, in the temple service. At Weimar he had developed into a great tone-poet of sacred song. With refined strength and exquisite perception he had gathered up the related parts of song, weaving them into a unity of impassioned and majestic utterance.

But the great poet must have a wider experience. He must enter, as it were, into the great deeps of sacred emotion in things natural; he must perceive in the universe a deeper, a more majestic beauty even than in the temple. Then he will become a great prophet among his fellows, and illumine for all time the pathway of life, giving strength to the weak, consolation to the weary, and song to the blithe and pure of heart. This is what Bach became in tone. His attention at Koethen was directed mainly to instrumental music.

We have previously remarked upon the endeavors which certain German masters made to bring home to their countrymen an appreciation of instrumental music. How long the seed lay germinating in Bach’s mind we know not. A new idea had taken possession of him, or, rather, he contemplated the application of the principle of his former labors in polyphony to instrumental music pure and simple.

At Koethen he supplemented his labors at Weimar. At Leipsic, whither we shall presently follow him, he brought them to completion.

But we are anticipating. We have seen how patiently, how toilsomely, Music has broken one by one the fetters of conventionality; how she has grown in strength and beauty, anticipating the moment of her final deliverance. It has come at last. With the patience and impatience of genius Bach strikes in twain the last fetter of conventionality. He has realized his quest. The boy who, far away in future thought, studied the art-forms of his great predecessors and contemporaries in the lowly chamber or by the light of the silent moon, has found his beloved, the Tonal Muse. She stands free before him to serve his will — his will purified by conception and incessant effort — and he will lead her in her new-found freedom and place her in the path of progress.

Bach’s compositions at this time include the early part of one of the greatest of his works, the Wohltemperirte Clavier. In this work — the second part of which was composed at Leipsic — Bach attained the full mastery of form. The strivings and efforts of the great Netherland masters found completion in this work of Bach. In it are compressed the labors of centuries. The works of the masters, Okeghem, Dufay, Josquin des Pres, and others, are but prophecies in tone, announcing a realization of their ideal in the centuries yet to come, that ideal which they felt so particularly, yet could not express. The Wohltemperirte Clavier then marks the first great climax of musical art.

The evolution was certain, and it consummated in a kindred mind. The deepest expression of human feeling, the agony of the dire distress and conflict of life, the calm majesty of faith which enables the soul to overcome every obstacle, its pathetic appeal to God for rest and comfort, the strength of victory, are possible in music, are expressed in music as no other art can express them, because of Bach.

True to his trust, he extracted all that was best in the works of his predecessors and, vivifying it by his genius, created forms of expression which the greatest that have followed him have utilized and extolled.

But, as we have said, the great poet must perceive in things natural, in the beauty of the universe around him, in the sacred feelings of human emotion, a sacredness as worthy and as earnest, though less concentrated in character, as that which exists in the more direct function of religious worship. To the great poet, however he works, all things are sacred. He it is who reveals the heaven that lies around us. He opens the portals of Nature, and we enter in to find strength and consolation.

Bach does all this in the masterly work we are considering. Not to the Italian, but to the German, did Nature at length disclose her choicest method of expression, and this because the German had ever lived in close contact with her. In all Bach’s works at this period the work of emancipation goes forward. Take, for instance, the Brandenburg concertos leading to the combination of the present orchestra.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.