This series has four easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Protestant Religious Influences on Bach.

Introduction

Bach is associated with the Baroque style of music but this series argues that he was much more. First, here’s a brief history of music before we begin Mr. Tipper.

Like the other arts and sciences, the story of music is that of a slow building up. Music “divinest of arts, exactest of sciences” — for music is both an art and a science — has developed from the crude two-or three-note scale melody, without semitones, to the elaborate, ornate lucubrations of the modern oratorio, opera, or symphony. From the beginning the “half-sister of Poetry” has been the handmaid of Religion. The ancients ascribed miraculous properties to music. Of the actual system of the Egyptians our information is very scant; but we learn from the monuments depicting the number and variety of their instruments that they had advanced from childish practice to orchestration and harmony. According to Plato, “In their possession are songs having the power to exalt and ennoble mankind.” The harp is undoubtedly of Egyptian origin.

The artistic standard of the music of the Greeks was far behind that of their observation and intelligence in other matters. Their theories on the combinations, of which they never made use, and analysis of their scales show much ingenuity, but their accounts are so vague that one cannot get any clear idea of what these were really like. When art is mature, people do not tell of city walls being overthrown, of savage animals being tamed — as run the stories of Orpheus and Amphion. One Greek there was, Pythagoras, who discerned the association between the distant music of the spheres with the seven notes of the scale. “He discovered the numerical relation of one tone to another.”[28] It was about the time of Pythagoras that a scheme of tetrachords which did not overlap was adopted.

In Persia and Arabia was obtained a perfect system of intonation. The Chinese system is minutely exact in theory, bombastic in fancy. The Hindus sedulously avoided applying mathematics to their scales. The development of the scale is shown in the construction of the ancient Greek scale, the modern Japanese, and the aboriginal Australian scale, and the phonographed tunes of some of the Red Indians of North America. Here a reference must be made to the scale of the Scotch bagpipe, a highly artificial product, without historical materials available to assist in unravelling its development. It comprises a whole diatonic series of notes, and modes may be selected therefrom.

But it is to Rome that we owe the seed of our modern methods of treatment. The Netherland school had been highly developed there by a long line of distinguished masters, who paved the way for the gifted Palestrina, who exalted polyphony to a secure eminence equal to that attained by the arts of painting and architecture. He brought forth a perception of the needs which music suffered, adding an earnestness and science to a profound quality of simpleness and grace. It was between 1561 and 1571 that his genius mellowed and his style took on those characteristics upon which was based the future music of the Catholic Church. It was while he was Maestro at the Vatican that he submitted to the Church the famed Missa Papæ Marcelli, which determined the future of church music.

This selection is from The Growth and Influence of Music in Relation to Civilization by Henry Tipper published in 1898.

Time: 1703 – 1750

Place: Germany

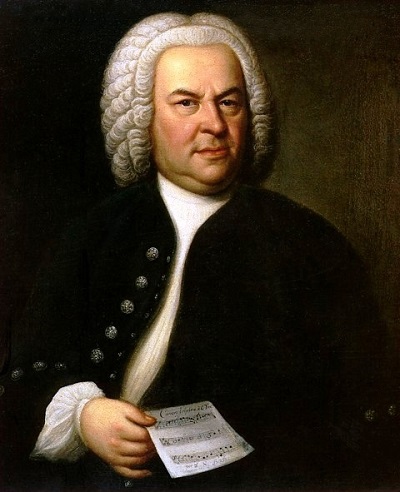

Public domain image from Wikipedia

The first tonal prophet and poet of the modern era, the era in which reason made tremendous protest against mere dogma, and the best religious instincts of human nature called imperatively for emancipation and for nearer individual contact with God, is Johann Sebastian Bach. We look dazzled at the brilliant victories of the Italian Renaissance, and amid tumultuous beauty run riot with imagination we hear the voice of Savonarola at the close of the period uttering his lamentations. The great Italian reformer saw and felt that in his own day and in his own country the glory and beauty of the movement had vanished in sensuality; that hardness of heart and indifference to primary human needs had diverted the waters of the Renaissance from their main fertilizing channel.

The deep need of the epoch was social, not mental, sociality in its widest sense: the right of the individual; his inherent majesty, which the accident of birth should not be able to impair — this and this only was the natural outcome of the new birth which came to humanity; this and this only was the sequel which German profundity and integrity, not Italian brilliancy and carelessness, placed before the mind of Europe.

The Reformation, then, this Protestantism, is distinctive of the new era. It was a protest, not only religious, as the word is usually applied, but scientific. It is the basis in the modern Western world of those laws of criticism which have submitted, or will submit, everything to searching analytical investigation, and as in the case of the natural world, so in the moral and ethical, men, by the light of revealed truth, or by those higher instincts of nobility which emanate from the Eternal Love, seek to apply to the reformation of society those principles of love, justice, and recompense which each would wish applied individually to self.

As an inspirer of thought and man of action, the world has seen few such men as Luther. His genius, as it were, discovered and laid bare the inexhaustible treasures of the German language; his sympathy and genial humanity sent a thrill of song, poetical and tonal, throughout the fatherland. He was the great awakener of German emotion. To Luther, a man who cared not for song was without the pale of humanity. But his enthusiasm was practical. In the church, as we have seen, he gathered from all sources whatever was of the best, and gave it to the people. In the schools he advocated the cause of song. In the streets the people needed not advocacy. Wherever two or three gathered together, song was in the midst of them, and it is not too much to say that the Lutheran hymn was the saviour of German poetry and a font of German song. In the seventeenth century there was in Germany little poetry worthy of the name save that inspired by the devotional character of Luther’s genius. His heir and successor in the realm of tone was Sebastian Bach.

True, two centuries had elapsed between the death of the great reformer in morals and the birth of the great reformer in tone; but the work of the latter could not have been without the former. The chorale was introduced by Luther; it was perfected by Bach. To what other influence than the Lutheran can we attribute the growth of Bach? Are there any other resources of German art and thought which can account for the advent of the great musician? In art Duerer stood by the side of Luther. In him again we find a man. Thought, thought! help me to express my native thought. Teach me to express in my art the reality of Nature, its wonderful beauty, thrice beautiful to me an artist; the pathos of life, its realism, far apparently from the ideal, yet most precious to me as a man. This was the aim of Duerer, and he seems a man after the Lutheran mould.

The aim of Duerer may be found in some respects in Bach’s work, because both men were men of integrity, great and patient in soul. This, of course, is not to say that Bach was affected by Duerer, but is merely an endeavor to find what was noblest in Germany preceding Bach. One more allusion. In Bach’s art we trace the mystic; not shadowy outpourings of hysterical emotion, but beauties of eternal verities disclosed in vision — faint, it is true — to none save the noblest of mortals.

One such kindred spirit preceding Bach was Boehme, the father of German mysticism, the poor cobbler, whose soul lay far away in the regions of celestial love, and whose utterance is of the realities thereof. These three men, Luther, Duerer, Boehme, are those to whom the great musician Bach is akin, but he is truly the child of the former, and the father of the highest aspirations in instrumental music.

For confirmatory evidence we have only to trace the growth of the Bach family. The progenitor, Veit Bach, was born at Wechmar, near Gotha, in 1550, and, following his trade as a baker, settled, after considerable wanderings, near the Hungarian frontier. Veit Bach was a stanch Lutheran. Whether the Lutheran services had given him a love of music, or whether they had only quickened a constitutional sympathy, it is impossible to say. Certain it is that he was passionately fond of music, and, cast for a period among a population whose emotions found constant and ready utterance in tone, he brought back to Wechmar, whither he had returned on account of religious persecution, his beloved cythringa and the art of playing it. There is evidence that this knowledge afforded him consolation and enjoyment in the quiet monotony of his life. While the mill was working, Veit Bach was often playing; and doubtless the peculiar charm and rhythm of old Hungarian melodies, songs of the people, which he had learned from the wandering gypsies, recurred to him, as well as those grand devotional hymns on which he had been nourished from childhood. We have said that Veit Bach was a stanch Lutheran. From father to son through generations, the Lutheran doctrine, pure and undefiled, had been handed down, accompanied by the musical gift, until both, uniting in Sebastian Bach, born at Eisenach in 1685, served to glorify the Lutheran chorale and the art which perfected it.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.