It stood where the present fort stands, in the angle formed by the junction of the River Niagara with Lake Ontario and was held by about six hundred men, well supplied with provisions and munitions of war.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 26.

It is true that some delay was inevitable. The French had four armed vessels on the lake and this made it necessary to provide an equal or superior force to protect the troops on their way to Isle-aux-Noix. Captain Loring, the English naval commander, was therefore ordered to build a brigantine; and, this being thought insufficient, he was directed to add a kind of floating battery, moved by sweeps. Three weeks later, in consequence of farther information concerning the force of the French vessels, Amherst ordered an armed sloop to be put on the stocks; and this involved a long delay. The sawmill at Ticonderoga was to furnish planks for the intended navy; but, being overtasked in sawing timber for the new works at Crown Point, it was continually breaking down. Hence much time was lost and autumn was well advanced before Loring could launch his vessels.

[1: Amherst to Pitt, 22 Oct. 1759. This letter, which is in the form of a journal, covers twenty-one folio pages.]

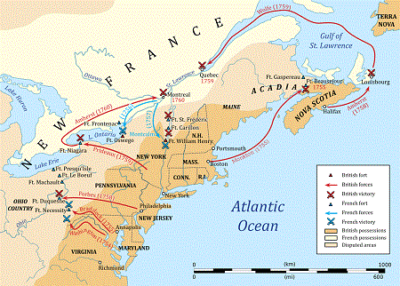

Meanwhile news had come from Prideaux and the Niagara expedition. That officer had been ordered to ascend the Mohawk with five thousand regulars and provincials, leave a strong garrison at Fort Stanwix, on the Great Carrying Place, establish posts at both ends of Lake Oneida, descend the Onondaga to Oswego, leave nearly half his force there under Colonel Haldimand and proceed with the rest to attack Niagara.[2] These orders he accomplished. Haldimand remained to reoccupy the spot that Montcalm had made desolate three years before; and, while preparing to build a fort, he barricaded his camp with pork and flour barrels, lest the enemy should make a dash upon him from their station at the head of the St. Lawrence Rapids. Such an attack was probable; for if the French could seize Oswego, the return of Prideaux from Niagara would be cut off and when his small stock of provisions had failed, he would be reduced to extremity. Saint-Luc de la Corne left the head of the Rapids early in July with a thousand French and Canadians and a body of Indians, who soon made their appearance among the stumps and bushes that surrounded the camp at Oswego. The priest Piquet was of the party; and five deserters declared that he solemnly blessed them and told them to give the English no quarter.[3] Some valuable time was lost in bestowing the benediction; yet Haldimand’s men were taken by surprise. Many of them were dispersed in the woods, cutting timber for the intended fort; and it might have gone hard with them had not some of La Corne’s Canadians become alarmed and rushed back to their boats, oversetting Father Piquet on the way.[4] These being rallied, the whole party ensconced itself in a tract of felled trees so far from the English that their fire did little harm. They continued it about two hours and resumed it the next morning; when, three cannon being brought to bear on them, they took to their boats and disappeared, having lost about thirty killed and wounded, including two officers and La Corne himself, who was shot in the thigh. The English loss was slight.

[2: Instructions of Amherst to Prideaux, 17 May, 1759. Prideaux to Haldimand, 30 June, 1759.]

[3: Journal of Colonel Amherst.]

[4: Pouchot, II. 130. Compare Mémoires sur le Canada, 1749-1760; N.Y. Col. Docs., VII. 395; and Letter from Oswego, in Boston Evening Post, No. 1,248.]

Prideaux safely reached Niagara and laid siege to it. It was a strong fort, lately rebuilt in regular form by an excellent officer, Captain Pouchot, of the battalion of Béarn, who commanded it. It stood where the present fort stands, in the angle formed by the junction of the River Niagara with Lake Ontario and was held by about six hundred men, well supplied with provisions and munitions of war.[5] Higher up the river, a mile and a half above the cataract, there was another fort, called Little Niagara, built of wood and commanded by the half-breed officer, Joncaire-Chabert, who with his brother, Joncaire-Clauzonne and a numerous clan of Indian relatives, had so long thwarted the efforts of Johnson to engage the Five Nations in the English cause. But recent English successes had had their effect. Joncaire’s influence was waning and Johnson was now in Prideaux’s camp with nine hundred Five Nation warriors pledged to fight the French. Joncaire, finding his fort untenable, burned it and came with his garrison and his Indian friends to reinforce Niagara.[6]

[5: Pouchot says 515, besides 60 men from Little Niagara; Vaudreuil gives a total of 589.]

[6: Pouchot, II. 52, 59. Procès de Bigot, Cadet, et autres, Mémoire pour Daniel de Joncaire-Chabert.]

Pouchot had another resource, on which he confidently relied. In obedience to an order from Vaudreuil, the French population of the Illinois, Detroit and other distant posts, joined with troops of Western Indians, had come down the Lakes to recover Pittsburg, undo the work of Forbes and restore French ascendency on the Ohio. Pittsburg had been in imminent danger; nor was it yet safe, though General Stanwix was sparing no effort to succor it.[7] These mixed bands of white men and red, bushrangers and savages, were now gathered, partly at Le Boeuf and Venango but chiefly at Presquisle, under command of Aubry, Ligneris, Marin and other partisan chiefs, the best in Canada. No sooner did Pouchot learn that the English were coming to attack him than he sent a messenger to summon them all to his aid.[8]

[7: Letters of Colonel Hugh Mercer, commanding at Pittsburg, January-June, 1759. Letters of Stanwix, May-July, 1759. Letter from Pittsburg, in Boston News Letter, No. 3,023. Narrative of John Ormsby.]

[8: Pouchot, II. 46.]

The siege was begun in form, though the English engineers were so incompetent that the trenches, as first laid out, were scoured by the fire of the place and had to be made anew.[9] At last the batteries opened fire. A shell from a coehorn burst prematurely, just as it left the mouth of the piece and a fragment striking Prideaux on the head, killed him instantly. Johnson took command in his place and made up in energy what he lacked in skill. In two or three weeks the fort was in extremity. The rampart was breached, more than a hundred of the garrison were killed or disabled and the rest were exhausted with want of sleep. Pouchot watched anxiously for the promised succors; and on the morning of the twenty-fourth of July a distant firing told him that they were at hand.

[9: Rutherford to Haldimand, 14 July, 1759. Prideaux was extremely disgusted. Prideaux to Haldimand, 13 July, 1759. Allan Macleane, of the Highlanders, calls the engineers “fools and blockheads, G — d d — n them.” Macleane to Haldimand, 21 July, 1759.]

Aubry and Ligneris, with their motley following, had left Presquisle a few days before, to the number, according to Vaudreuil, of eleven hundred French and two hundred Indians.[10] Among them was a body of colony troops; but the Frenchmen of the party were chiefly traders and bushrangers from the West, connecting links between civilization and savagery; some of them indeed were mere white Indians, imbued with the ideas and morals of the wigwam, wearing hunting-shirts of smoked deer-skin embroidered with quills of the Canada porcupine, painting their faces black and red, tying eagle feathers in their long hair, or plastering it on their temples with a compound of vermilion and glue. They were excellent woodsmen, skillful hunters and perhaps the best bush-fighters in all Canada.

[10: “Il n’y avoit que 1,100 François et 200 sauvages.” Vaudreuil au Ministre, 30 Oct. 1759. Johnson says “1,200 men, with a number of Indians.” Johnson to Amherst, 25 July, 1759. Portneuf, commanding at Presquisle, wrote to Pouchot that there were 1,600 French and 1,200 Indians. Pouchot, II. 94. A letter from Aubry to Pouchot put the whole at 2,500, half of them Indians. Historical Magazine, V., Second Series, 199.]

When Pouchot heard the firing, he went with a wounded artillery officer to the bastion next the river; and as the forest had been cut away for a great distance, they could see more than a mile and a half along the shore. There, by glimpses among trees and bushes, they descried bodies of men, now advancing and now retreating; Indians in rapid movement and the smoke of guns, the sound of which reached their ears in heavy volleys, or a sharp and angry rattle. Meanwhile the English cannon had ceased their fire and the silent trenches seemed deserted, as if their occupants were gone to meet the advancing foe. There was a call in the fort for volunteers to sally and destroy the works; but no sooner did they show themselves along the covered way than the seemingly abandoned trenches were thronged with men and bayonets and the attempt was given up. The distant firing lasted half an hour, then ceased and Pouchot remained in suspense; till, at two in the afternoon, a friendly Onondaga, who had passed unnoticed through the English lines, came to him with the announcement that the French and their allies had been routed and cut to pieces. Pouchot would not believe him.

Nevertheless, his tale was true. Johnson, besides his Indians, had with him about twenty-three hundred men, whom he was forced to divide into three separate bodies, — one to guard the bateaux, one to guard the trenches and one to fight Aubry and his band. This last body consisted of the provincial light infantry and the pickets, two companies of grenadiers and a hundred and fifty men of the forty-sixth regiment, all under command of Colonel Massey.[11] They took post behind an abattis at a place called La Belle Famille and the Five Nation warriors placed themselves on their flanks. These savages had shown signs of disaffection; and when the enemy approached, they opened a parley with the French Indians, which, however, soon ended and both sides raised the war-whoop. The fight was brisk for a while; but at last Aubry’s men broke away in a panic. The French officers seem to have made desperate efforts to retrieve the day, for nearly all of them were killed or captured; while their followers, after heavy loss, fled to their canoes and boats above the cataract, hastened back to Lake Erie, burned Presquisle, Le Boeuf and Venango and, joined by the garrisons of those forts, retreated to Detroit, leaving the whole region of the upper Ohio in undisputed possession of the English.

[11: Johnson to Amherst, 25 July, 1759. Knox, II. 135. Captain Delancey to — — , 25 July, 1759. This writer commanded the light infantry in the fight.]

At four o’clock on the day of the battle, after a furious cannonade on both sides, a trumpet sounded from the trenches and an officer approached the fort with a summons to surrender. He brought also a paper containing the names of the captive French officers, though some of them were spelled in a way that defied recognition. Pouchot, feigning incredulity, sent an officer of his own to the English camp, who soon saw unanswerable proof of the disaster; for here, under a shelter of leaves and boughs near the tent of Johnson, sat Ligneris, severely wounded, with Aubry, Villiers, Montigny, Marin and their companions in misfortune, — in all, sixteen officers, four cadets and a surgeon.

[12: Johnson gives the names in his private Diary, printed in Stone, Life of Johnson, II. 394. Compare Pouchot, II. 105, 106. Letter from Niagara, in Boston Evening Post, No. 1,250. Vaudreuil au Ministre, 30 Oct. 1759.]

Pouchot had now no choice but surrender. By the terms of the capitulation, the garrison were to be sent prisoners to New York, though honors of war were granted them in acknowledgment of their courageous conduct. There was a special stipulation that they should be protected from the Indians, of whom they stood in the greatest terror, lest the massacre of Fort William Henry should be avenged upon them. Johnson restrained his dangerous allies and, though the fort was pillaged, no blood was shed.

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 26 by Francis Parkman

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.