While Quebec was attacked, an attempt should be made to penetrate into Canada by way of Ticonderoga and Crown Point.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 25.

NOTE: Among the killed in this affair was Edward Botwood, sergeant in the grenadiers of the forty-seventh, or Lascelles’ regiment. “Ned Botwood” was well known among his comrades as a poet; and the following lines of his, written on the eve of the expedition to Quebec, continued to be favorites with the British troops during the War of the Revolution (see Historical Magazine, II., First Series, 164). It may be observed here that the war produced a considerable quantity of indifferent verse on both sides. On that of the English it took the shape of occasional ballads, such as “Bold General Wolfe,” printed on broadsides, or of patriotic effusions scattered through magazines and newspapers, while the French celebrated all their victories with songs.

HOT STUFF.

Air, — Lilies of France.

Come, each death-doing dog who dares venture his neck, Come, follow the hero that goes to Quebec; Jump aboard of the transports and loose every sail, Pay your debts at the tavern by giving leg-bail; And ye that love fighting shall soon have enough: Wolfe commands us, my boys; we shall give them Hot Stuff.

Up the River St. Lawrence our troops shall advance, To the Grenadiers’ March we will teach them to dance. Cape Breton we have taken and next we will try At their capital to give them another black eye. Vaudreuil ‘t is in vain you pretend to look gruff, — Those are coming who know how to give you Hot Stuff.

With powder in his periwig and snuff in his nose, Monsieur will run down our descent to oppose; And the Indians will come: but the light infantry Will soon oblige them to betake to a tree. From such rascals as these may we fear a rebuff? Advance, grenadiers and let fly your Hot Stuff!

When the forty-seventh regiment is dashing ashore, While bullets are whistling and cannons do roar, Says Montcalm: “Those are Shirley’s — I know the lappels.” “You lie,” says Ned Botwood, “we belong to Lascelles’! Tho’ our cloathing is changed, yet we scorn a powder-puff; So at you, ye b — — s, here’s give you Hot Stuff.” P/

On the repulse at Montmorenci, Wolfe to Pitt, 2 Sept. 1759. Vaudreuil au Ministre, 5 Oct. 1759. Panet, Journal du Siége. Johnstone, Dialogue in Hades. Journal tenu à l’Armée, etc. Journal of the Siege of Quebec, by a Gentleman in an eminent Station on the Spot. Mémoires sur le Canada, 1749-1760. Fraser, Journal of the Siege. Journal du Siége d’après un MS. déposé à la Bibliothêque Hartwell. Foligny, Journal mémoratif. Journal of Transactions at the Siege of Quebec, in Notes and Queries, XX. 164. John Johnson, Memoirs of the Siege of Quebec. Journal of an Expedition on the River St. Lawrence. An Authentic Account of the Expedition against Quebec, by a Volunteer on that Expedition. J. Gibson to Governor Lawrence, 1 Aug. 1759. Knox, I. 354. Mante, 244.

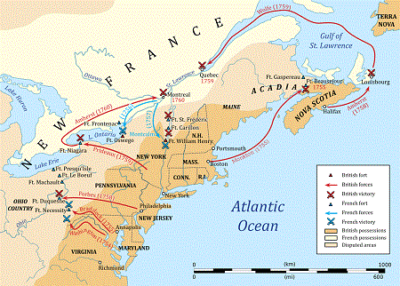

Pitt had directed that, while Quebec was attacked, an attempt should be made to penetrate into Canada by way of Ticonderoga and Crown Point. Thus, the two armies might unite in the heart of the colony or, at least, a powerful diversion might be effected in behalf of Wolfe. At the same time Oswego was to be re-established and the possession of Fort Duquesne, or Pittsburg, secured by reinforcements and supplies; while Amherst, the commander-in-chief, was further directed to pursue any other enterprise which in his opinion would weaken the enemy, without detriment to the main objects of the campaign.[1] He accordingly resolved to attempt the capture of Niagara. Brigadier Prideaux was charged with this stroke; Brigadier Stanwix was sent to conduct the operations for the relief of Pittsburg; and Amherst himself prepared to lead the grand central advance against Ticonderoga, Crown Point and Montreal.[2]

[1: Pitt to Amherst, 23 Jan., 10 March, 1759.]

[2: Amherst to Pitt, 19 June, 1759. Amherst to Stanwix, 6 May, 1759.]

Towards the end of June he reached that valley by the head of Lake George which for five years past had been the annual mustering-place of armies. Here were now gathered about eleven thousand men, half regulars and half provincials,[3] drilling every day, firing by platoons, firing at marks, practicing maneuvers in the woods; going out on scouting parties, bathing parties, fishing parties; gathering wild herbs to serve for greens, cutting brushwood and meadow hay to make hospital beds. The sick were ordered on certain mornings to repair to the surgeon’s tent, there, in prompt succession, to swallow such doses as he thought appropriate to their several ailments; and it was further ordered that “every fair day they that can walk be paraded together and marched down to the lake to wash their hands and faces.” Courts-martial were numerous; culprits were flogged at the head of each regiment in turn and occasionally one was shot. A frequent employment was the cutting of spruce tops to make spruce beer. This innocent beverage was reputed sovereign against scurvy; and such was the fame of its virtues that a copious supply of the West Indian molasses used in concocting it was thought indispensable to every army or garrison in the wilderness. Throughout this campaign it is repeatedly mentioned in general orders and the soldiers are promised that they shall have as much of it as they want at a halfpenny a quart.[4]

[3: Mante, 210.]

[4: Orderly Book of Commissary Wilson in the Expedition against Ticonderoga, 1759. Journal of Samuel Warner, a Massachusetts Soldier, 1759. General and Regimental Orders, Army of Major-General Amherst, 1759. Diary of Sergeant Merriman, of Ruggles’s Regiment, 1759. I owe to William L. Stone, Esq., the use of the last two curious documents.]

The rear of the-army was well protected from insult. Fortified posts were built at intervals of three or four miles along the road to Fort Edward and especially at the station called Half-way Brook; while, for the whole distance, a broad belt of wood on both sides was cut down and burned, to deprive a skulking enemy of cover. Amherst was never long in one place without building a fort there. He now began one, which proved wholly needless, on that flat rocky hill where the English made their intrenched camp during the siege of Fort William Henry. Only one bastion of it was ever finished and this is still shown to tourists under the name of Fort George.

The army embarked on Saturday, the twenty-first of July. The Reverend Benjamin Pomeroy watched their departure in some concern and wrote on Monday to Abigail, his wife: “I could wish for more appearance of dependence on God than was observable among them; yet I hope God will grant deliverance unto Israel by them.” There was another military pageant, another long procession of boats and banners, among the mountains and islands of Lake George. Night found them near the outlet; and here they lay till morning, tossed unpleasantly on waves ruffled by a summer gale. At daylight they landed, beat back a French detachment and marched by the portage road to the saw-mill at the waterfall. There was little resistance. They occupied the heights and then advanced to the famous line of intrenchment against which the army of Abercromby had hurled itself in vain. These works had been completely reconstructed, partly of earth and partly of logs. Amherst’s followers were less numerous than those of his predecessor, while the French commander, Bourlamaque, had a force nearly equal to that of Montcalm in the summer before; yet he made no attempt to defend the intrenchment and the English, encamping along its front, found it an excellent shelter from the cannon of the fort beyond.

Amherst brought up his artillery and began approaches in form, when, on the night of the twenty-third, it was found that Bourlamaque had retired down Lake Champlain, leaving four hundred men under Hebecourt to defend the place as long as possible. This was in obedience to an order from Vaudreuil, requiring him on the approach of the English to abandon both Ticonderoga and Crown Point, retreat to the outlet of Lake Champlain, take post at Isle-aux-Noix and there defend himself to the last extremity;[5] a course unquestionably the best that could have been taken, since obstinacy in holding Ticonderoga might have involved the surrender of Bourlamaque’s whole force, while Isle-aux-Noix offered rare advantages for defense.

[5: Vaudreuil au Ministre, 8 Nov. 1759. Instructions pour M. de Bourlamaque, 20 Mai, 1759, signé Vaudreuil. Montcalm à Bourlamaque, 4 Juin, 1759.]

The fort fired briskly; a cannon-shot killed Colonel Townshend and a few soldiers were killed and wounded by grape and bursting shells; when, at dusk on the evening of the twenty-sixth, an unusual movement was seen among the garrison and, about ten o’clock, three deserters came in great excitement to the English camp. They reported that Hebecourt and his soldiers were escaping in their boats and that a match was burning in the magazine to blow Ticonderoga to atoms. Amherst offered a hundred guineas to any one of them who would point out the match, that it might be cut; but they shrank from the perilous venture. All was silent till eleven o’clock, when a broad, fierce glare burst on the night and a roaring explosion shook the promontory; then came a few breathless moments and then the fragments of Fort Ticonderoga fell with clatter and splash on the water and the land. It was but one bastion, however, that had been thus hurled skyward. The rest of the fort was little hurt, though the barracks and other combustible parts were set on fire and by the light the French flag was seen still waving on the rampart.[6] A sergeant of the light infantry, braving the risk of other explosions, went and brought it off. Thus did this redoubted stronghold of France fall at last into English hands, as in all likelihood it would have done a year sooner, if Amherst had commanded in Abercromby’s place; for, with the deliberation that marked all his proceedings, he would have sat down before Montcalm’s wooden wall and knocked it to splinters with his cannon.

[6: Journal of Colonel Amherst (brother of General Amherst). Vaudreuil au Ministre, 8 Nov. 1759. Amherst to Prideaux, 28 July, 1759. Amherst to Pitt, 27 July, 1759. Mante, 213. Knox, I., 397-403. Vaudreuil à Bourlamaque, 19 Juin, 1759.]

He now set about repairing the damaged works and making ready to advance on Crown Point; when on the first of August his scouts told him that the enemy had abandoned this place also and retreated northward down the lake.[728] Well pleased, he took possession of the deserted fort and, in the animation of success, thought for a moment of keeping the promise he had given to Pitt “to make an irruption into Canada with the utmost vigor and dispatch.”[7] Wolfe, his brother in arms and his friend, was battling with the impossible under the rocks of Quebec and every motive, public and private, impelled Amherst to push to his relief, not counting costs, or balancing risks too nicely. He was ready enough to spur on others, for he wrote to Gage: “We must all be alert and active day and night; if we all do our parts the French must fall;”[8] but, far from doing his, he set the army to building a new fort at Crown Point, telling them that it would “give plenty, peace and quiet to His Majesty’s subjects for ages to come.”[9] Then he began three small additional forts, as outworks to the first, sent two parties to explore the sources of the Hudson; one party to explore Otter Creek; another to explore South Bay, which was already well known; another to make a road across what is now the State of Vermont, from Crown Point to Charlestown, or “Number Four,” on the Connecticut; and another to widen and improve the old French road between Crown Point and Ticonderoga. His industry was untiring; a great deal of useful work was done: but the essential task of making a diversion to aid the army of Wolfe was needlessly postponed.

[7: Amherst to Pitt, 5 Aug. 1759.]

[8: Ibid., 19 June, 1759.]

[9: Amherst to Gage, 1 Aug. 1759.]

[10: General Orders, 13 Aug. 1759.]

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 26 by Francis Parkman

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.