In the city itself every gate, except the Palace Gate, which gave access to the bridge, was closed and barricaded. A hundred and six cannon were mounted on the walls.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series.

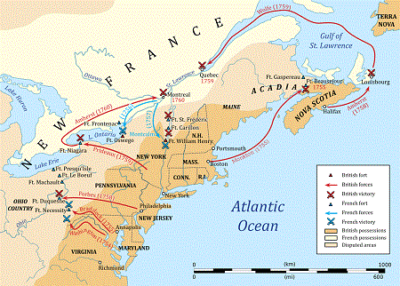

In early spring the chiefs of Canada met at Montreal to settle a plan of defense. What at first they most dreaded was an advance of the enemy by way of Lake Champlain. Bourlamaque, with three battalions, was ordered to take post at Ticonderoga, hold it if he could, or, if overborne by numbers, fall back to Isle-aux-Noix, at the outlet of the lake. La Corne was sent with a strong detachment to intrench himself at the head of the rapids of the St. Lawrence and oppose any hostile movement from Lake Ontario. Every able-bodied man in the colony and every boy who could fire a gun, was to be called to the field. Vaudreuil sent a circular letter to the militia captains of all the parishes, with orders to read it to the parishioners. It exhorted them to defend their religion, their wives, their children and their goods from the fury of the heretics; declared that he, the Governor, would never yield up Canada on any terms whatever; and ordered them to join the army at once, leaving none behind but the old, the sick, the women and the children.[1] The Bishop issued a pastoral mandate: “On every side, dearest brethren, the enemy is making immense preparations. His forces, at least six times more numerous than ours, are already in motion. Never was Canada in a state so critical and full of peril. Never were we so destitute, or threatened with an attack so fierce, so general and so obstinate. Now, in truth, we may say, more than ever before, that our only resource is in the powerful succor of our Lord. Then, dearest brethren, make every effort to deserve it. ‘Seek first the kingdom of God; and all these things shall be added unto you.'” And he reproves their sins, exhorts them to repentance and ordains processions, masses and prayers.[2]

[1: Mémoires sur le Canada, 1749-1760.]

[2: I am indebted for a copy of this mandate to the kindness of Abbé Bois. As printed by Knox, it is somewhat different, though the spirit is the same.]

Vaudreuil bustled and boasted. In May he wrote to the Minister:

The zeal with which I am animated for the service of the King will always make me surmount the greatest obstacles. I am taking the most proper measures to give the enemy a good reception whenever he may attack us. I keep in view the defense of Quebec. I have given orders in the parishes below to muster the inhabitants who are able to bear arms and place women, children, cattle and even hay and grain, in places of safety. Permit me, Monseigneur, to beg you to have the goodness to assure His Majesty that, to whatever hard extremity I may be reduced, my zeal will be equally ardent and indefatigable and that I shall do the impossible to prevent our enemies from making progress in any direction, or, at least, to make them pay extremely dear for it.”

[3: Vaudreuil au Ministre, 8 Mai, 1759.]

Then he writes again to say that Amherst with a great army will, as he learns, attack Ticonderoga; that Bradstreet, with six thousand men, will advance to Lake Ontario; and that six thousand more will march to the Ohio. “Whatever progress they may make,” he adds, “I am resolved to yield them nothing but hold my ground even to annihilation.” He promises to do his best to keep on good terms with Montcalm and ends with a warm eulogy of Bigot.

[4: Vaudreuil au Ministre, 20 [?] Mai, 1759.]

It was in the midst of all these preparations that Bougainville arrived from France with news that a great fleet was on its way to attack Quebec. The town was filled with consternation mixed with surprise, for the Canadians had believed that the dangerous navigation of the St. Lawrence would deter their enemies from the attempt. “Everybody,” writes one of them, “was stupefied at an enterprise that seemed so bold.” In a few days a crowd of sails was seen approaching. They were not enemies but friends. It was the fleet of the contractor Cadet, commanded by officer named Kanon and loaded with supplies for the colony. They anchored in the harbor, eighteen sail in all and their arrival spread universal joy. Admiral Durell had come too late to intercept them, catching but three stragglers that had lagged behind the rest. Still others succeeded in eluding him and before the first of June five more ships had come safely into port.

When the news brought by Bougainville reached Montreal, nearly the whole force of the colony, except the detachments of Bourlamaque and La Corne, was ordered to Quebec. Montcalm hastened thither and Vaudreuil followed. The Governor-General wrote to the Minister in his usual strain, as if all the hope of Canada rested in him. Such, he says, was his activity, that, though very busy, he reached Quebec only a day and a half after Montcalm; and, on arriving, learned from his scouts that English ships-of-war had already appeared at Isle-aux-Coudres. These were the squadron of Durell. “I expect,” Vaudreuil goes on, “to be sharply attacked and that our enemies will make their most powerful efforts to conquer this colony; but there is no ruse, no resource, no means which my zeal does not suggest to lay snares for them and finally, when the exigency demands it, to fight them with an ardor and even a fury, which exceeds the range of their ambitious designs. The troops, the Canadians and the Indians are not ignorant of the resolution I have taken and from which I shall not recoil under any circumstance whatever. The burghers of this city have already put their goods and furniture in places of safety. The old men, women and children hold themselves ready to leave town. My firmness is generally applauded. It has penetrated every heart; and each man says aloud: ‘Canada, our native land, shall bury us under its ruins before we surrender to the English!’ This is decidedly my own determination and I shall hold to it inviolably.” He launches into high praise of the contractor Cadet, whose zeal for the service of the King and the defense of the colony he declares to be triumphant over every difficulty. It is necessary, he adds, that ample supplies of all kinds should be sent out in the autumn, with the distribution of which Cadet offers to charge himself and to account for them at their first cost; but he does not say what prices his disinterested friend will compel the destitute Canadians to pay for them.

[5: Vaudreuil au Ministre, 28 Mai, 1759.]

Five battalions from France, nearly all the colony troops and the militia from every part of Canada poured into Quebec, along with a thousand or more Indians, who, at the call of Vaudreuil, came to lend their scalping-knives to the defense. Such was the ardor of the people that boys of fifteen and men of eighty were to be seen in the camp. Isle-aux-Coudres and Isle d’Orléans were ordered to be evacuated and an excited crowd on the rock of Quebec watched hourly for the approaching fleet. Days passed and weeks passed, yet it did not appear. Meanwhile Vaudreuil held council after council to settle a plan of defense, They were strange scenes: a crowd of officers of every rank, mixed pell-mell in a small room, pushing, shouting, elbowing each other, interrupting each other; till Montcalm in despair, took each aside after the meeting was over and made him give his opinion in writing.

[6: Journal du Siége de Québec déposé à la Bibliothêque de Hartwell, en Angleterre. (Printed at Quebec, 1836.)]

He himself had at first proposed to encamp the army on the plains of Abraham and the meadows of the St. Charles, making that river his line of defense;[7] but he changed his plan and, with the concurrence of Vaudreuil, resolved to post his whole force on the St. Lawrence below the city, with his right resting on the St. Charles and his left on the Montmorenci. Here, accordingly, the troops and militia were stationed as they arrived. Early in June, standing at the northeastern brink of the rock of Quebec, one could have seen the whole position at a glance. On the curving shore from the St. Charles to the rocky gorge of the Montmorenci, a distance of seven or eight miles, the whitewashed dwellings of the parish of Beauport stretched down the road in a double chain and the fields on both sides were studded with tents, huts and Indian wigwams. Along the borders of the St. Lawrence, as far as the eye could distinguish them, gangs of men were throwing up redoubts, batteries and lines of intrenchment. About midway between the two extremities of the encampment ran the little river of Beauport; and on the rising ground just beyond it stood a large stone house, round which the tents were thickly clustered; for here Montcalm had made his headquarters.

[7: Livre d’Ordres, Disposition pour s’opposer à la Descente.]

A boom of logs chained together was drawn across the mouth of the St. Charles, which was further guarded by two hulks mounted with cannon. The bridge of boats that crossed the stream nearly a mile above, formed the chief communication between the city and the camp. Its head towards Beauport was protected by a strong and extensive earthwork; and the banks of the stream on the Quebec side were also intrenched, to form a second line of defense in case the position at Beauport should be forced.

In the city itself every gate, except the Palace Gate, which gave access to the bridge, was closed and barricaded. A hundred and six cannon were mounted on the walls.[8] A floating battery of twelve heavy pieces, a number of gunboats, eight fireships and several firerafts formed the river defenses. The largest merchantmen of Kanon’s fleet were sacrificed to make the fireships; and the rest, along with the frigates that came with them, were sent for safety up the St. Lawrence beyond the River Richelieu, whence about a thousand of their sailors returned to man the batteries and gunboats.

[8: This number was found after the siege. Knox, II. 151. Some French writers make it much greater.]

In the camps along the Beauport shore were about fourteen thousand men, besides Indians. The regulars held the center; the militia of Quebec and Three Rivers were on the right and those of Montreal on the left. In Quebec itself there was a garrison of between one and two thousand men under the Chevalier de Ramesay. Thus, the whole number, including Indians, amounted to more than sixteen thousand and though the Canadians who formed the greater part of it were of little use in the open field, they could be trusted to fight well behind intrenchments. Against this force, posted behind defensive works, on positions almost impregnable by nature, Wolfe brought less than nine thousand men available for operations on land. The steep and lofty heights that lined the river made the cannon of the ships for the most part useless, while the exigencies of the naval service forbade employing the sailors on shore. In two or three instances only, throughout the siege, small squads of them landed to aid in moving and working cannon; and the actual fighting fell to the troops alone.

Vaudreuil and Bigot took up their quarters with the army. The Governor-General had delegated the command of the land-forces to Montcalm, whom, in his own words, he authorized “to give orders everywhere, provisionally.” His relations with him were more than ever anomalous and critical; for while Vaudreuil, in virtue of his office, had a right to supreme command, Montcalm, now a lieutenant-general, held a military grade far above him; and the Governor, while always writing himself down in his dispatches as the head and front of every movement, had too little self-confidence not to leave the actual command in the hands of his rival.

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 25 by Francis Parkman

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.