For the last time, I exhort you to give these things your serious attention, for they will not escape from mine.”

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 17.

Canada was the prey of official jackals, — true lion’s providers, since they helped to prepare a way for the imperial beast, who, roused at last from his lethargy, was gathering his strength to seize her for his own. Honesty could not be expected from a body of men clothed with arbitrary and ill-defined powers, ruling with absolute sway an unfortunate people who had no voice in their own destinies and answerable only to an apathetic master three thousand miles away. Nor did the Canadian Church, though supreme, check the corruptions that sprang up and flourished under its eye. The Governor himself was charged with sharing the plunder; and though he was acquitted on his trial, it is certain that Bigot had him well in hand, that he was intimate with the chief robbers and that they found help in his weak compliances and willful blindness. He put his stepson, Le Verrier, in command at Michillimackinac, where, by fraud and the connivance of his stepfather, the young man made a fortune.[1] When the Colonial Minister berated the Intendant for maladministration, Vaudreuil became his advocate and wrote thus in his defense: “I cannot conceal from you, Monseigneur, how deeply M. Bigot feels the suspicions expressed in your letters to him. He does not deserve them, I am sure. He is full of zeal for the service of the King; but as he is rich, or passes as such and as he has merit, the ill-disposed are jealous and insinuate that he has prospered at the expense of His Majesty. I am certain that it is not true and that nobody is a better citizen than he, or has the King’s interest more at heart.”[2] For Cadet, the butcher’s son, the Governor asked a patent of nobility as a reward for his services.[3] When Péan went to France in 1758, Vaudreuil wrote to the Colonial Minister: “I have great confidence in him. He knows the colony and its needs. You can trust all he says. He will explain everything in the best manner. I shall be extremely sensible to any kindness you may show him and hope that when you know him you will like him as much as I do.”[4]

[1: Mémoires sur le Canada, 1749-1760.]

[2: Vaudreuil au Ministre, 15 Oct. 1759.]

[3: Ibid., 7 Nov. 1759.]

[4: Ibid., 6 Août, 1758.]

Administrative corruption was not the only bane of Canada. Her financial condition was desperate. The ordinary circulating medium consisted of what was known as card money and amounted to only a million of francs. This being insufficient, Bigot, like his predecessor Hocquart, issued promissory notes on his own authority and made them legal tender. They were for sums from one franc to a hundred and were called ordonnances. Their issue was blamed at Versailles as an encroachment on the royal prerogative, though they were recognized by the Ministry in view of the necessity of the case. Every autumn those who held them to any considerable amount might bring them to the colonial treasurer, who gave in return bills of exchange on the royal treasury in France. At first these bills were promptly paid; then delays took place and the notes depreciated; till in 1759 the Ministry, aghast at the amount, refused payment and the utmost dismay and confusion followed.

[Réflections sommaires sur le Commerce qui s’est fait en Canada. État présent du Canada. Compare Stevenson, Card Money of Canada, in Transactions of the Historical Society of Quebec, 1873-1875.]

The vast jarring, discordant mechanism of corruption grew incontrollable; it seized upon Bigot and dragged him, despite himself, into perils which his prudence would have shunned. He was becoming a victim to the rapacity of his own confederates, whom he dared not offend by refusing his connivance and his signature of frauds which became more and more recklessly audacious. He asked leave to retire from office, in the hope that his successor would bear the brunt of the ministerial displeasure. Péan had withdrawn already and with the fruits of his plunder bought land in France, where he thought himself safe. But though the Intendant had long been an object of distrust and had often been warned to mend his ways,[5] yet such was his energy, his executive power and his fertility of resource, that in the crisis of the war it was hard to dispense with him. Neither his abilities, however, nor his strong connections in France, nor an ally whom he had secured in the bureau of the Colonial Minister himself, could avail him much longer; and the letters from Versailles became appalling in rebuke and menace.

[5: Ordres du Roy et Dépêches des Ministres, 1751-1758.]

“The ship ‘Britannia,'” wrote the Minister, Berryer,

laden with goods such as are wanted in the colony, was captured by a privateer from St. Malo and brought into Quebec. You sold the whole cargo for eight hundred thousand francs. The purchasers made a profit of two millions. You bought back a part for the King at one million, or two hundred thousand more than the price which you sold the whole. With conduct like this it is no wonder that the expenses of the colony become insupportable. The amount of your drafts on the treasury is frightful. The fortunes of your subordinates throw suspicion on your administration.”

And in another letter on the same day:

How could it happen that the small-pox among the Indians cost the King a million francs? What does this expense mean? Who is answerable for it? Is it the officers who command the posts, or is it the storekeepers? You give me no particulars. What has become of the immense quantity of provisions sent to Canada last year? I am forced to conclude that the King’s stores are set down as consumed from the moment they arrive and then sold to His Majesty at exorbitant prices. Thus, the King buys stores in France and then buys them again in Canada. I no longer wonder at the immense fortunes made in the colony.”[6]

Some months later the Minister writes:

You pay bills without examination and then find an error in your accounts of three million six hundred thousand francs. In the letters from Canada I see nothing but incessant speculation in provisions and goods, which are sold to the King for ten times more than they cost in France. For the last time, I exhort you to give these things your serious attention, for they will not escape from mine.”[7]

[6: Le Ministre à Bigot, 19 Jan. 1759.]

[7: Ibid., 29 Août, 1759.]

I write, Monsieur, to answer your last two letters, in which you tell me that instead of sixteen millions, your drafts on the treasury for 1758 will reach twenty-four millions and that this year they will rise to from thirty-one to thirty-three millions. It seems, then, that there are no bounds to the expenses of Canada. They double almost every year, while you seem to give yourself no concern except to get them paid. Do you suppose that I can advise the King to approve such an administration? or do you think that you can take the immense sum of thirty-three millions out of the royal treasury by merely assuring me that you have signed drafts for it? This, too, for expenses incurred irregularly, often needlessly, always wastefully; which make the fortune of everybody who has the least hand in them and about which you know so little that after reporting them at sixteen millions, you find two months after that they will reach twenty-four. You are accused of having given the furnishing of provisions to one man, who under the name of commissary-general, has set what prices he pleased; of buying for the King at second or third hand what you might have got from the producer at half the price; of having in this and other ways made the fortunes of persons connected with you; and of living in splendor in the midst of a public misery, which all the letters from the colony agree in ascribing to bad administration and in charging M. de Vaudreuil with weakness in not preventing.”

[Le Ministre à Bigotû, 29 Août, 1759 (second letter of this date).]

These drastic utterances seem to have been partly due to a letter written by Montcalm in cipher to the Maréchal de Belleisle, then minister of war. It painted the deplorable condition of Canada and exposed without reserve the peculations and robberies of those entrusted with its interests. “It seems,” said the General, “as if they were all hastening to make their fortunes before the loss of the colony; which many of them perhaps desire as a veil to their conduct.” He gives among other cases that of Le Mercier, chief of Canadian artillery, who had come to Canada as a private soldier twenty years before and had so prospered on fraudulent contracts that he would soon be worth nearly a million. “I have often,” continues Montcalm, “spoken of these expenditures to M. de Vaudreuil and M. Bigot; and each throws the blame on the other.”[8] And yet at the same time Vaudreuil was assuring the Minister that Bigot was without blame.

[8: Montcalm au Ministre de la Guerre, Lettre confidentielle, 12 Avril, 1759.]

Some two months before Montcalm wrote this letter, the Minister, Berryer, sent a dispatch to the Governor and Intendant which filled them with ire and mortification. It ordered them to do nothing without consulting the general of the French regulars, not only in matters of war but in all matters of administration touching the defense and preservation of the colony. A plainer proof of confidence on one hand and distrust on the other could not have been given.

[Le Ministre à Vaudreuil et Bigot, 20 Fév. 1759.]

One Querdisien-Tremais was sent from Bordeaux as an agent of Government to make investigation. He played the part of detective, wormed himself into the secrets of the confederates and after six months of patient inquisition traced out four distinct combinations for public plunder. Explicit orders were now given to Bigot, who, seeing no other escape, broke with Cadet and made him disgorge two millions of stolen money. The Commissary-General and his partners became so terrified that they afterwards gave up nearly seven millions more.[9] Stormy events followed and the culprits found shelter for a time amid the tumults of war. Peculation did not cease but a day of reckoning was at hand.

[9: Procès de Bigot, Cadet, et autres, Mémoirs pour François Bigot, 3’me partie.]

NOTE: The printed documents of the trial of Bigot and the other peculators include the defense of Bigot, of which the first part occupies 303 quarto pages and the second part 764. Among the other papers are the arguments for Péan, Varin, Saint-Blin, Boishébert, Martel, Joncaire-Chabert and several more, along with the elaborate Jugement rendue, the Requêtes du Procureur-Général, the Réponse aux Mémoires de M. Bigot et du Sieur Péan, etc., forming together five quarto volumes, all of which I have carefully examined. These are in the Library of Harvard University. There is another set, also of five volumes, in the Library of the Historical Society of Quebec, containing most of the papers just mentioned and, bound with them, various others in manuscript, among which are documents in defense of Vaudreuil (printed in part); Estèbe, Corpron, Penisseault, Maurin and Bréard. I have examined this collection also. The manuscript Ordres du Roy et Dépêches des Ministres, 1757-1760, as well as the letters of Vaudreuil, Bougainville, Daine, Doreil and Montcalm throw much light on the maladministration of the time; as do many contemporary documents, notably those entitled Mémoire sur les Fraudes commises dans la Colonie, État présent du Canada, and Mémoire sur le Canada (Archives Nationales). The remarkable anonymous work printed by the Historical Society of Quebec under the title Mémoires sur le Canada depuis 1749 jusqu’àé 1760, is full of curious matter concerning Bigot and his associates which squares well with other evidence. This is the source from which Smith, in his History of Canada (Quebec, 1815), drew most of his information on the subject. A manuscript which seems to be the original draft of this valuable document was preserved at the Bastile and, with other papers, was thrown into the street when that castle was destroyed. They were gathered up and afterwards bought by a Russian named Dubrowski, who carried them to St. Petersburg. Lord Dufferin, when minister there, procured a copy of the manuscript in question, which is now in the keeping of Abbé H. Verreau at Montreal, to whose kindness I owe the opportunity of examining it. In substance it differs little from the printed work, though the language and the arrangement often vary from it. The author, whoever he may have been, was deeply versed in Canadian affairs of the time and though often caustic, is generally trustworthy.

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 17 by Francis Parkman

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

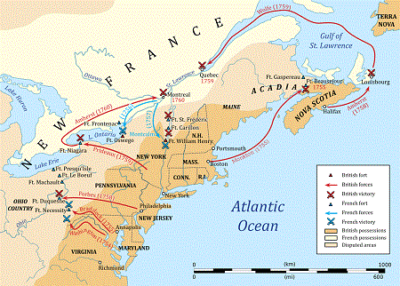

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.