Since Vaudreuil became chief of the colony he had nursed the plan of seizing Oswego, yet hesitated to attempt it.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 12.

That night his sleep was broken and his soul troubled by angry voices under his window, where one Colonel Glasier was berating, in unhallowed language, the captain of the guard; and here the chaplain’s Journal abruptly ends.

[I owe to my friend George S. Hale, Esq., the opportunity of examining the autograph Journal; it has since been printed in the Magazine of American History for March, 1882.]

A brother minister, bearing no likeness to the worthy Graham, appeared on the same spot some time after. This was Chaplain William Crawford, of Worcester, who, having neglected to bring money to the war, suffered much annoyance, aggravated by what he thought a want of due consideration for his person and office. His indignation finds vent in a letter to his townsman, Timothy Paine, member of the General Court: “No man can reasonably expect that I can with any propriety discharge the duty of a chaplain when I have nothing either to eat or drink, nor any conveniency to write a line other than to sit down upon a stump and put a piece of paper upon my knee. As for Mr. Weld [another chaplain], he is easy and silent whatever treatment he meets with, and I suppose they thought to find me the same easy and ductile person; but may the wide yawning earth devour me first! The state of the camp is just such as one at home would guess it to be, — nothing but a hurry and confusion of vice and wickedness, with a stygian atmosphere to breathe in.” [1] The vice and wickedness of which he complains appear to have consisted in a frequent infraction of the standing order against “Curseing and Swareing,” as well as of that which required attendance on daily prayers, and enjoined “the people to appear in a decent manner, clean and shaved,” at the two Sunday sermons. [2]

[1: The autograph letter is in Massachusetts Archives, LVI. no. 142. The same volume contains a letter from Colonel Frye, of Massachusetts, in which he speaks of the forlorn condition in which Chaplain Weld reached the camp. Of Chaplain Crawford, he says that he came decently clothed, but without bed or blanket, till he, Frye, lent them to him, and got Captain Learned to take him into his tent. Chaplains usually had a separate tent, or shared that of the colonel.]

[2: Letter and Order Books of Winslow.]

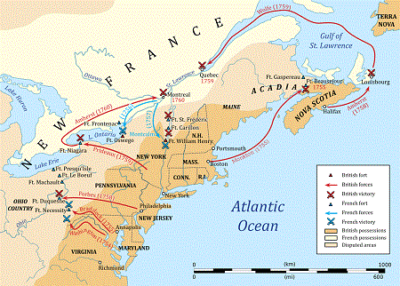

At the beginning of August Winslow wrote to the committees of the several provinces: “It looks as if it won’t be long before we are fit for a remove,” — that is, for an advance on Ticonderoga. On the twelfth Loudon sent Webb with the forty-fourth regiment and some of Bradstreet’s boatmen to reinforce Oswego. [3] They had been ready for a month; but confusion and misunderstanding arising from the change of command had prevented their departure. [4] Yet the utmost anxiety had prevailed for the safety of that important post, and on the twenty-eighth Surgeon Thomas Williams wrote: “Whether Oswego is yet ours is uncertain. Would hope it is, as the reverse would be such a terrible shock as the country never felt and may be a sad omen of what is coming upon poor sinful New England. Indeed we can’t expect anything but to be severely chastened till we are humbled for our pride and haughtiness.” [5]

[3: Loudon (to Fox?), 19 Aug. 1756.]

[4: Conduct of Major-General Shirley briefly stated. Shirley to Loudon, 4 Sept. 1756. Shirley to Fox, 16 Sept. 1756.]

[5: Thomas Williams to Colonel Israel Williams, 28 Aug. 1756.]

His foreboding proved true. Webb had scarcely reached the Great Carrying Place, when tidings of disaster fell upon him like a thunderbolt. The French had descended in force upon Oswego, taken it with all its garrison; and, as report ran, were advancing into the province, six thousand strong. Wood Creek had just been cleared, with great labor, of the trees that choked it. Webb ordered others to be felled and thrown into the stream to stop the progress of the enemy; then, with shameful precipitation, he burned the forts of the Carrying Place, and retreated down the Mohawk to German Flats. Loudon ordered Winslow to think no more of Ticonderoga, but to stay where he was and hold the French in check. All was astonishment and dismay at the sudden blow. “Oswego has changed masters, and I think we may justly fear that the whole of our country will soon follow, unless a merciful God prevent, and awake a sinful people to repentance and reformation.” Thus wrote Dr. Thomas Williams to his wife from the camp at Fort Edward. “Such a shocking affair has never found a place in English annals,” wrote the surgeon’s young relative, Colonel William Williams. “The loss is beyond account; but the dishonor done His Majesty’s arms is infinitely greater.” [6] It remains to see how the catastrophe befell.

[6: Colonel William Williams to Colonel Israel Williams, 30 Aug. 1756].

Since Vaudreuil became chief of the colony he had nursed the plan of seizing Oswego, yet hesitated to attempt it. Montcalm declares that he confirmed the Governor’s wavering purpose; but Montcalm himself had hesitated. In July, however, there came exaggerated reports that the English were moving upon Ticonderoga in greatly increased numbers; and both Vaudreuil and the General conceived that a feint against Oswego would draw off the strength of the assailants, and, if promptly and secretly executed, might even be turned successfully into a real attack. Vaudreuil thereupon recalled Montcalm from Ticonderoga. [7] Leaving the post in the keeping of Lévis and three thousand men, he embarked on Lake Champlain, rowed day and night, and reached Montreal on the nineteenth. Troops were arriving from Quebec, and Indians from the far west. A band of Menomonies from beyond Lake Michigan, naked, painted, plumed, greased, stamping, uttering sharp yelps, shaking feathered lances, brandishing tomahawks, danced the war-dance before the Governor, to the thumping of the Indian drum. Bougainville looked on astonished and thought of the Pyrrhic dance of the Greeks.

[7: Vaudreuil au Ministre, 12 Août, 1756. Montcalm à sa Femme, 20 Juillet, 1756.]

Montcalm and he left Montreal on the twenty-first and reached Fort Frontenac in eight days. Rigaud, brother of the Governor, had gone thither some time before, and crossed with seven hundred Canadians to the south side of the lake, where Villiers was encamped at Niaouré Bay, now Sackett’s Harbor, with such of his detachment as war and disease had spared. Rigaud relieved him and took command of the united bands. With their aid the engineer, Descombles, reconnoitered the English forts, and came back with the report that success was certain. [8] It was but a confirmation of what had already been learned from deserters and prisoners, who declared that the main fort was but a loopholed wall held by six or seven hundred men, ill fed, discontented, and mutinous. [9] Others said that they had been driven to desert by the want of good food, and that within a year twelve hundred men had died of disease at Oswego. [10]

[8: Vaudreuil au Ministre, 4 Août, 1756. Vaudreuil à Bourlamaque, — Juin, 1756.]

[9: Bougainville, Journal.]

[10: Vaudreuil au Ministre, 10 Juillet, 1756. Résumé des Nouvelles du Canada, Sept. 1756.]

The battalions of La Sarre, Guienne, and Béarn, with the colony regulars, a body of Canadians, and about two hundred and fifty Indians, were destined for the enterprise. The whole force was a little above three thousand, abundantly supplied with artillery. La Sarre and Guienne were already at Fort Frontenac. Béarn was at Niagara, whence it arrived in a few days, much buffeted by the storms of Lake Ontario. On the fourth of August all was ready. Montcalm embarked at night with the first division, crossed in darkness to Wolf Island, lay there hidden all day, and embarking again in the evening, joined Rigaud at Niaouré Bay at seven o’clock in the morning of the sixth. The second division followed, with provisions, hospital train, and eighty artillery boats; and on the eighth all were united at the bay. On the ninth Rigaud, covered by the universal forest, marched in advance to protect the landing of the troops. Montcalm followed with the first division; and, coasting the shore in bateaux, landed at midnight of the tenth within half a league of the first English fort. Four cannon were planted in battery upon the strand and the men bivouacked by their boats. So skillful were the assailants and so careless the assailed that the English knew nothing of their danger, till in the morning, a reconnoitering canoe discovered the invaders. Two armed vessels soon came to cannonade them; but their light guns were no match for the heavy artillery of the French, and they were forced to keep the offing.

Descombles, the engineer, went before dawn to reconnoiter the fort, with several other officers and a party of Indians. While he was thus employed, one of these savages, hungry for scalps, took him in the gloom for an Englishman, and shot him dead. Captain Pouchot, of the battalion of Béarn, replaced him; and the attack was pushed vigorously. The Canadians and Indians, swarming through the forest, fired all day on the fort under cover of the trees. The second division came up with twenty-two more cannon; and at night the first parallel was marked out at a hundred and eighty yards from the rampart. Stumps were grubbed up, fallen trunks shoved aside, and a trench dug, sheltered by fascines, gabions, and a strong abattis.

Fort Ontario, counted as the best of the three forts at Oswego, stood on a high plateau at the east or right side of the river where it entered the lake. It was in the shape of a star and was formed of trunks of trees set upright in the ground, hewn flat on two sides, and closely fitted together, — an excellent defense against musketry or swivels, but worthless against cannon. The garrison, three hundred and seventy in all, were the remnant of Pepperell’s regiment, joined to raw recruits lately sent up to fill the places of the sick and dead. They had eight small cannon and a mortar, with which on the next day, Friday, the thirteenth, they kept up a brisk fire till towards night; when, after growing more rapid for a time, it ceased, and the fort showed no sign of life. Not a cannon had yet opened on them from the trenches; but it was certain that with the French artillery once in action, their wooden rampart would be shivered to splinters. Hence it was that Colonel Mercer, commandant at Oswego, thinking it better to lose the fort than to lose both fort and garrison, signaled to them from across the river to abandon their position and join him on the other side. Boats were sent to bring them off; and they passed over unmolested, after spiking their cannon and firing off their ammunition or throwing it into the well.

The fate of Oswego was now sealed. The principal work, called Old Oswego, or Fort Pepperell, stood at the mouth of the river on the west side, nearly opposite Fort Ontario, and less than five hundred yards distant from it. The trading-house, which formed the center of the place, was built of rough stone laid in clay, and the wall which enclosed it was of the same materials; both would crumble in an instant at the touch of a twelve-pound shot. Towards the west and south they had been protected by an outer line of earthworks, mounted with cannon, and forming an entrenched camp; while the side towards Fort Ontario was left wholly exposed, in the rash confidence that this work, standing on the opposite heights, would guard against attack from that quarter. On a hill, a fourth of a mile beyond Old Oswego, stood the unfinished stockade called New Oswego, Fort George, or, by reason of its worthlessness, Fort Rascal. It had served as a cattle pen before the French appeared but was now occupied by a hundred and fifty Jersey provincials. Old Oswego with its outwork was held by Shirley’s regiment, chiefly invalids and raw recruits, to whom were now joined the garrison of Fort Ontario and a number of sailors, boatmen, and laborers.

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 12 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.