The most beautiful lake in America lay before them; then more beautiful than now, in the wild charm of untrodden mountains and virgin forests.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 9.

[1: Papers of Colonel Israel Williams.]

[2: Massachusetts Archives.]

[3: Jonathan Caswell to John Caswell, 6 July, 1755.]

To Pomeroy and some of his brothers in arms it seemed that they were engaged in a kind of crusade against the myrmidons of Rome. “As you have at heart the Protestant cause,” he wrote to his friend Israel Williams, “so I ask an interest in your prayers that the Lord of Hosts would go forth with us and give us victory over our unreasonable, encroaching, barbarous, murdering enemies.”

Both Williams the surgeon and Williams the colonel chafed at the incessant delays. “The expedition goes on very much as a snail runs,” writes the former to his wife; “it seems we may possibly see Crown Point this time twelve months.” The Colonel was vexed because everything was out of joint in the department of transportation: wagoners mutinous for want of pay; ordnance stores, camp-kettles, and provisions left behind. “As to rum,” he complains, “it won’t hold out nine weeks. Things appear most melancholy to me.” Even as he was writing, a report came of the defeat of Braddock; and, shocked at the blow, his pen traced the words: “The Lord have mercy on poor New England!”

Johnson had sent four Mohawk scouts to Canada. They returned on the twenty-first of August with the report that the French were all astir with preparation, and that eight thousand men were coming to defend Crown Point. On this a council of war was called; and it was resolved to send to the several colonies for reinforcements. [4] Meanwhile the main body had moved up the river to the spot called the Great Carrying Place, where Lyman had begun a fortified storehouse, which his men called Fort Lyman, but which was afterwards named Fort Edward. Two Indian trails led from this point to the waters of Lake Champlain, one by way of Lake George, and the other by way of Wood Creek. There was doubt which course the army should take. A road was begun to Wood Creek; then it was countermanded, and a party was sent to explore the path to Lake George. “With submission to the general officers,” Surgeon Williams again writes, “I think it a very grand mistake that the business of reconnoitering was not done months agone.” It was resolved at last to march for Lake George; gangs of axe-men were sent to hew out the way; and on the twenty-sixth two thousand men were ordered to the lake, while Colonel Blanchard, of New Hampshire, remained with five hundred to finish and defend Fort Lyman.

[4: Minutes of Council of War, 22 Aug. 1755. Ephraim Williams to Benjamin Dwight, 22 Aug. 1755.]

The train of Dutch wagons, guarded by the homely soldiery, jolted slowly over the stumps and roots of the newly made road, and the regiments followed at their leisure. The hardships of the way were not without their consolations. The jovial Irishman who held the chief command made himself very agreeable to the New England officers. “We went on about four or five miles,” says Pomeroy in his Journal, “then stopped, ate pieces of broken bread and cheese, and drank some fresh lemon-punch and the best of wine with General Johnson and some of the field-officers.” It was the same on the next day. “Stopped about noon and dined with General Johnson by a small brook under a tree; ate a good dinner of cold boiled and roast venison; drank good fresh lemon-punch and wine.”

That afternoon they reached their destination, fourteen miles from Fort Lyman. The most beautiful lake in America lay before them; then more beautiful than now, in the wild charm of untrodden mountains and virgin forests. “I have given it the name of Lake George,” wrote Johnson to the Lords of Trade, “not only in honor of His Majesty, but to ascertain his undoubted dominion here.” His men made their camp on a piece of rough ground by the edge of the water, pitching their tents among the stumps of the newly felled trees. In their front was a forest of pitch-pine; on their right, a marsh, choked with alders and swamp-maples; on their left, the low hill where Fort George was afterwards built; and at their rear, the lake. Little was done to clear the forest in front, though it would give excellent cover to an enemy. Nor did Johnson take much pains to learn the movements of the French in the direction of Crown Point, though he sent scouts towards South Bay and Wood Creek. Everyday stores and bateaux, or flat boats, came on wagons from Fort Lyman; and preparation moved on with the leisure that had marked it from the first. About three hundred Mohawks came to the camp and were regarded by the New England men as nuisances. On Sunday the gray-haired Stephen Williams preached to these savage allies a long Calvinistic sermon, which must have sorely perplexed the interpreter whose business it was to turn it into Mohawk; and in the afternoon young Chaplain Newell, of Rhode Island, expounded to the New England men the somewhat untimely text, “Love your enemies.” On the next Sunday, September seventh, Williams preached again, this time to the whites from a text in Isaiah. It was a peaceful day, fair and warm, with a few light showers; yet not wholly a day of rest, for two hundred wagons came up from Fort Lyman, loaded with bateaux. After the sermon there was an alarm. An Indian scout came in about sunset and reported that he had found the trail of a body of men moving from South Bay towards Fort Lyman. Johnson called for a volunteer to carry a letter of warning to Colonel Blanchard, the commander. A wagoner named Adams offered himself for the perilous service, mounted, and galloped along the road with the letter. Sentries were posted, and the camp fell asleep.

[5: Vaudreuil au Ministre, 25 Sept. 1755].

[6: Livre d’Ordres, Août, Sept. 1755.]

The Indians allies were commanded by Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, the officer who had received Washington on his embassy to Fort Le Bœuf. These unmanageable warriors were a constant annoyance to Dieskau, being a species of humanity quite new to him. “They drive us crazy,” he says, “from morning till night. There is no end to their demands. They have already eaten five oxen and as many hogs, without counting the kegs of brandy they have drunk. In short, one needs the patience of an angel to get on with these devils; and yet one must always force himself to seem pleased with them.”

[Dieskau à Vaudreuil, 1 Sept. 1755.]

They would scarcely even go out as scouts. At last, however, on the fourth of September, a reconnoitering party came in with a scalp and an English prisoner caught near Fort Lyman. He was questioned under the threat of being given to the Indians for torture if he did not tell the truth but, nothing daunted, he invented a patriotic falsehood and, thinking to lure his captors into a trap, told them that the English army had fallen back to Albany, leaving five hundred men at Fort Lyman, which he represented as indefensible. Dieskau resolved on a rapid movement to seize the place. At noon of the same day, leaving a part of his force at Ticonderoga, he embarked the rest in canoes and advanced along the narrow prolongation of Lake Champlain that stretched southward through the wilderness to where the town of Whitehall now stands. He soon came to a point where the lake dwindled to a mere canal, while two mighty rocks, capped with stunted forests, faced each other from the opposing banks. Here he left an officer named Roquemaure with a detachment of troops, and again advanced along a belt of quiet water traced through the midst of a deep marsh, green at that season with sedge and water-weeds and known to the English as the Drowned Lands. Beyond, on either hand, crags feathered with birch and fir, or hills mantled with woods, looked down on the long procession of canoes. [7] As they neared the site of Whitehall, a passage opened on the right, the entrance to a sheet of lonely water slumbering in the shadow of woody mountains, and forming the lake then, as now, called South Bay. They advanced to its head, landed where a small stream enters it, left the canoes under a guard, and began their march through the forest. They counted in all two hundred and sixteen regulars of the battalions of Languedoc and La Reine, six hundred and eighty-four Canadians, and above six hundred Indians. [8] Every officer and man carried provisions for eight days in his knapsack. They encamped at night by a brook, and in the morning, after hearing Mass, marched again. The evening of the next day brought them near the road that led to Lake George. Fort Lyman was but three miles distant. A man on horseback galloped by; it was Adams, Johnson’s unfortunate messenger. The Indians shot him, and found the letter in his pocket. Soon after, ten or twelve wagons appeared in charge of mutinous drivers, who had left the English camp without orders. Several of them were shot, two were taken, and the rest ran off. The two captives declared that, contrary to the assertion of the prisoner at Ticonderoga, a large force lay encamped at the lake. The Indians now held a council, and presently gave out that they would not attack the fort, which they thought well supplied with cannon, but that they were willing to attack the camp at Lake George. Remonstrance was lost upon them. Dieskau was not young, but he was daring to rashness, and inflamed to emulation by the victory over Braddock. The enemy were reported greatly to outnumber him; but his Canadian advisers had assured him that the English colony militia were the worst troops on the face of the earth. “The more there are,” he said to the Canadians and Indians, “the more we shall kill;” and in the morning the order was given to march for the lake.

[7: I passed this way three weeks ago. There are some points where the scene is not much changed since Dieskau saw it.]

[8: Mémoire sur l’Affaire du 8 Septembre.]

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 9 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

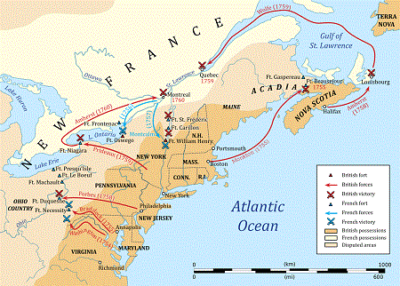

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.