The British waited until the Acadian farmers had brought in the harvest to surprise them, seize them, and imprison them.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 8.

Thus, ruffled in spirit, he embarked with his men and sailed down Chignecto Channel to the Bay of Fundy. Here, while they waited the turn of the tide to enter the Basin of Mines, the shores of Cumberland lay before them dim in the hot and hazy air, and the promontory of Cape Split, like some misshapen monster of primeval chaos, stretched its portentous length along the glimmering sea, with head of yawning rock, and ridgy back bristled with forests. Borne on the rushing flood, they soon drifted through the inlet, glided under the rival promontory of Cape Blomedon, passed the red sandstone cliffs of Lyon’s Cove, and descried the mouths of the rivers Canard and Des Habitants, where fertile marshes, diked against the tide, sustained a numerous and thriving population. Before them spread the boundless meadows of Grand Pré, waving with harvests or alive with grazing cattle; the green slopes behind were dotted with the simple dwellings of the Acadian farmers, and the spire of the village church rose against a background of woody hills. It was a peaceful, rural scene, soon to become one of the most wretched spots on earth. Winslow did not land for the present but held his course to the estuary of the River Pisiquid, since called the Avon. Here, where the town of Windsor now stands, there was a stockade called Fort Edward, where a garrison of regulars under Captain Alexander Murray kept watch over the surrounding settlements. The New England men pitched their tents on shore, while the sloops that had brought them slept on the soft bed of tawny mud left by the fallen tide.

Winslow found a warm reception, for Murray and his officers had been reduced too long to their own society not to welcome the coming of strangers. The two commanders conferred together. Both had been ordered by Lawrence to “clear the whole country of such bad subjects;” and the methods of doing so had been outlined for their guidance. Having come to some understanding with his brother officer concerning the duties imposed on both and begun an acquaintance which soon grew cordial on both sides, Winslow embarked again and retraced his course to Grand Pré, the station which the Governor had assigned him. “Am pleased,” he wrote to Lawrence, “with the place proposed by your Excellency for our reception [the village church]. I have sent for the elders to remove all sacred things, to prevent their being defiled by heretics.” The church was used as a storehouse and place of arms; the men pitched their tents between it and the graveyard; while Winslow took up his quarters in the house of the priest, where he could look from his window on a tranquil scene. Beyond the vast tract of grassland to which Grand Pré owed its name, spread the blue glistening breast of the Basin of Mines; beyond this again, the distant mountains of Cobequid basked in the summer sun; and nearer, on the left, Cape Blomedon reared its bluff head of rock and forest above the sleeping waves.

As the men of the settlement greatly outnumbered his own, Winslow set his followers to surrounding the camp with a stockade. Card-playing was forbidden, because it encouraged idleness, and pitching quoits in camp, because it spoiled the grass. Presently there came a letter from Lawrence expressing a fear that the fortifying of the camp might alarm the inhabitants. To which Winslow replied that the making of the stockade had not alarmed them in the least, since they took it as a proof that the detachment was to spend the winter with them; and he added, that as the harvest was not yet got in, he and Murray had agreed not to publish the Governor’s commands till the next Friday. He concludes: “Although it is a disagreeable part of duty we are put upon, I am sensible it is a necessary one, and shall endeavor strictly to obey your Excellency’s orders.”

On the thirtieth, Murray, whose post was not many miles distant, made him a visit. They agreed that Winslow should summon all the male inhabitants about Grand Pré to meet him at the church and hear the King’s orders, and that Murray should do the same for those around Fort Edward. Winslow then called in his three captains, — Adams, Hobbs, and Osgood, — made them swear secrecy, and laid before them his instructions and plans; which latter they approved. Murray then returned to his post, and on the next day sent Winslow a note containing the following: “I think the sooner we strike the stroke the better, therefore will be glad to see you here as soon as conveniently you can. I shall have the orders for assembling ready written for your approbation, only the day blank, and am hopeful everything will succeed according to our wishes. The gentlemen join me in our best compliments to you and the Doctor.”

On the next day, Sunday, Winslow and the Doctor, whose name was Whitworth, made the tour of the neighborhood, with an escort of fifty men, and found a great quantity of wheat still on the fields. On Tuesday Winslow “set out in a whale-boat with Dr. Whitworth and Adjutant Kennedy, to consult with Captain Murray in this critical conjuncture.” They agreed that three in the afternoon of Friday should be the time of assembling; then between them they drew up a summons to the inhabitants, and got one Beauchamp, a merchant, to “put it into French.” It ran as follows:

By John Winslow, Esquire, Lieutenant-Colonel and Commander of His Majesty’s troops at Grand Pré, Mines, River Canard, and places adjacent.

To the inhabitants of the districts above named, as well ancients as young men and lads.

Whereas His Excellency the Governor has instructed us of his last resolution respecting the matters proposed lately to the inhabitants, and has ordered us to communicate the same to the inhabitants in general in person, His Excellency being desirous that each of them should be fully satisfied of His Majesty’s intentions, which he has also ordered us to communicate to you, such as they have been given him.

We therefore order and strictly enjoin by these presents to all the inhabitants, as well of the above-named districts as of all the other districts, both old men and young men, as well as all the lads of ten years of age, to attend at the church in Grand Pré on Friday, the fifth instant, at three of the clock in the afternoon, that we may impart what we are ordered to communicate to them; declaring that no excuse will be admitted on any pretense whatsoever, on pain of forfeiting goods and chattels in default.

Given at Grand Pré, the second of September, in the twenty-ninth year of His Majesty’s reign, a.d. 1755.”

A similar summons was drawn up in the name of Murray for the inhabitants of the district of Fort Edward.

Captain Adams made a reconnaissance of the rivers Canard and Des Habitants, and reported “a fine country and full of inhabitants, a beautiful church, and abundance of the goods of the world.” Another reconnaissance by Captains Hobbs and Osgood among the settlements behind Grand Pré brought reports equally favorable. On the fourth, another letter came from Murray: “All the people quiet, and very busy at their harvest; if this day keeps fair, all will be in here in their barns. I hope to-morrow will crown all our wishes.” The Acadians, like the bees, were to gather a harvest for others to enjoy. The summons was sent out that afternoon. Powder and ball were served to the men, and all were ordered to keep within the lines.

On the next day the inhabitants appeared at the hour appointed, to the number of four hundred and eighteen men. Winslow ordered a table to be set in the middle of the church and placed on it his instructions and the address he had prepared. Here he took his stand in his laced uniform, with one or two subalterns from the regulars at Fort Edward, and such of the Massachusetts officers as were not on guard duty; strong, sinewy figures, bearing, no doubt, more or less distinctly, the peculiar stamp with which toil, trade, and Puritanism had imprinted the features of New England. Their commander was not of the prevailing type. He was fifty-three years of age, with double chin, smooth forehead, arched eyebrows, close powdered wig, and round, rubicund face, from which the weight of an odious duty had probably banished the smirk of self-satisfaction that dwelt there at other times. [1] Nevertheless, he had manly and estimable qualities. The congregation of peasants, clad in rough homespun, turned their sunburned faces upon him, anxious and intent; and Winslow “delivered them by interpreters the King’s orders in the following words,” which, retouched in orthography and syntax, ran thus:

Gentlemen, — I have received from His Excellency, Governor Lawrence, the King’s instructions, which I have in my hand. By his orders you are called together to hear His Majesty’s final resolution concerning the French inhabitants of this his province of Nova Scotia, who for almost half a century have had more indulgence granted them than any of his subjects in any part of his dominions. What use you have made of it you yourselves best know.

The duty I am now upon, though necessary, is very disagreeable to my natural make and temper, as I know it must be grievous to you, who are of the same species. But it is not my business to animadvert on the orders I have received, but to obey them; and therefore without hesitation I shall deliver to you His Majesty’s instructions and commands, which are that your lands and tenements and cattle and live-stock of all kinds are forfeited to the Crown, with all your other effects, except money and household goods, and that you yourselves are to be removed from this his province.

The peremptory orders of His Majesty are that all the French inhabitants of these districts be removed; and through His Majesty’s goodness I am directed to allow you the liberty of carrying with you your money and as many of your household goods as you can take without overloading the vessels you go in. I shall do everything in my power that all these goods be secured to you, and that you be not molested in carrying them away, and also that whole families shall go in the same vessel; so that this removal, which I am sensible must give you a great deal of trouble, may be made as easy as His Majesty’s service will admit; and I hope that in whatever part of the world your lot may fall, you may be faithful subjects, and a peaceable and happy people.

I must also inform you that it is His Majesty’s pleasure that you remain in security under the inspection and direction of the troops that I have the honor to command.”

[1: See his portrait, at the rooms of the Massachusetts Historical Society.]

He then declared them prisoners of the King. “They were greatly struck,” he says, “at this determination, though I believe they did not imagine that they were actually to be removed.” After delivering the address, he returned to his quarters at the priest’s house, whither he was followed by some of the elder prisoners, who begged leave to tell their families what had happened, “since they were fearful that the surprise of their detention would quite overcome them.” Winslow consulted with his officers, and it was arranged that the Acadians should choose twenty of their number each day to revisit their homes, the rest being held answerable for their return.

A letter, dated some days before, now came from Major Handfield at Annapolis, saying that he had tried to secure the men of that neighborhood, but that many of them had escaped to the woods. Murray’s report from Fort Edward came soon after and was more favorable: “I have succeeded finely, and have got a hundred and eighty-three men into my possession.” To which Winslow replies: “I have the favor of yours of this day, and rejoice at your success, and also for the smiles that have attended the party here.” But he adds mournfully: “Things are now very heavy on my heart and hands.” The prisoners were lodged in the church, and notice was sent to their families to bring them food. “Thus,” says the Diary of the commander, “ended the memorable fifth of September, a day of great fatigue and trouble.”

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 8 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

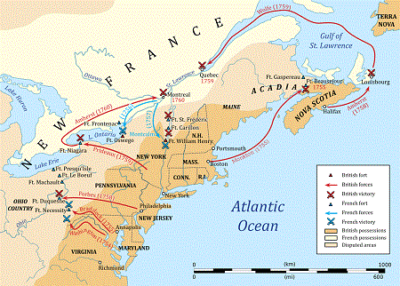

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.