Washington’s letter had contained the astonishing announcement that Dunbar meant to abandon the frontier and march to Philadelphia.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 7.

Colonel James Innes, commanding at Fort Cumberland, where a crowd of invalids with soldiers’ wives and other women had been left when the expedition marched, heard of the defeat, only two days after it happened, from a wagoner who had fled from the field on horseback. He at once sent a note of six lines to Lord Fairfax: “I have this moment received the most melancholy news of the defeat of our troops, the General killed, and numbers of our officers; our whole artillery taken. In short, the account I have received is so very bad, that as, please God, I intend to make a stand here, ’tis highly necessary to raise the militia everywhere to defend the frontiers.” A boy whom he sent out on horseback met more fugitives and came back on the fourteenth with reports as vague and disheartening as the first. Innes sent them to Dinwiddie. [1] Some days after, Dunbar and his train arrived in miserable disorder, and Fort Cumberland was turned into a hospital for the shattered fragments of a routed and ruined army.

[1: Innes to Dinwiddie, 14 July, 1755.]

On the sixteenth a letter was brought in haste to one Buchanan at Carlisle, on the Pennsylvanian frontier:

Sir, — I thought it proper to let you know that I was in the battle where we were defeated. And we had about eleven hundred and fifty private men, besides officers and others. And we were attacked the ninth day about twelve o’clock, and held till about three in the afternoon, and then we were forced to retreat, when I suppose we might bring off about three hundred whole men, besides a vast many wounded. Most of our officers were either wounded or killed; General Braddock is wounded, but I hope not mortal; and Sir John Sinclair and many others, but I hope not mortal. All the train is cut off in a manner. Sir Peter Halket and his son, Captain Polson, Captain Gethan, Captain Rose, Captain Tatten killed, and many others. Captain Ord of the train is wounded, but I hope not mortal. We lost all our artillery entirely, and everything else.

To Mr. John Smith and Buchannon, and give it to the next post, and let him show this to Mr. George Gibson in Lancaster, and Mr. Bingham, at the sign of the Ship, and you’ll oblige,

Yours to command,

John Campbell, Messenger.”

[Colonial Records of Pa., VI. 481.]

The evil tidings quickly reached Philadelphia, where such confidence had prevailed that certain over-zealous persons had begun to collect money for fireworks to celebrate the victory. Two of these, brother physicians named Bond, came to Franklin and asked him to subscribe; but the sage looked doubtful. “Why, the devil!” said one of them, “you surely don’t suppose the fort will not be taken?” He reminded them that war is always uncertain; and the subscription was deferred. [2] The Governor laid the news of the disaster before his Council, telling them at the same time that his opponents in the Assembly would not believe it, and had insulted him in the street for giving it currency. [3]

[2: Autobiography of Franklin.]

[3: Colonial Records of Pa., VI. 480.]

Dinwiddie remained tranquil at Williamsburg, sure that all would go well. The brief note of Innes, forwarded by Lord Fairfax, first disturbed his dream of triumph; but on second thought he took comfort. “I am willing to think that account was from a deserter who, in a great panic, represented what his fears suggested. I wait with impatience for another express from Fort Cumberland, which I expect will greatly contradict the former.” The news got abroad, and the slaves showed signs of excitement. “The villany of the negroes on any emergency is what I always feared,” continues the Governor. “An example of one or two at first may prevent these creatures entering into combinations and wicked designs.” [4] And he wrote to Lord Halifax: “The negro slaves have been very audacious on the news of defeat on the Ohio. These poor creatures imagine the French will give them their freedom. We have too many here; but I hope we shall be able to keep them in proper subjection.” Suspense grew intolerable. “It’s monstrous they should be so tardy and dilatory in sending down any farther account.” He sent Major Colin Campbell for news; when, a day or two later, a courier brought him two letters, one from Orme, and the other from Washington, both written at Fort Cumberland on the eighteenth. The letter of Orme began thus: “My dear Governor, I am so extremely ill in bed with the wound I have received that I am under the necessity of employing my friend Captain Dobson as my scribe.” Then he told the wretched story of defeat and humiliation. “The officers were absolutely sacrificed by their unparalleled good behavior; advancing before their men sometimes in bodies, and sometimes separately, hoping by such an example to engage the soldiers to follow them; but to no purpose. Poor Shirley was shot through the head, Captain Morris very much wounded. Mr. Washington had two horses shot under him, and his clothes shot through in several places; behaving the whole time with the greatest courage and resolution.”

[4: Dinwiddie to Colonel Charles Carter, 18 July, 1755.]

Washington wrote more briefly, saying that, as Orme was giving a full account of the affair, it was needless for him to repeat it. Like many others in the fight, he greatly underrated the force of the enemy, which he placed at three hundred, or about a third of the actual number,–a natural error, as most of the assailants were invisible. “Our poor Virginians behaved like men, and died like soldiers; for I believe that out of three companies that were there that day, scarce thirty were left alive. Captain Peronney and all his officers down to a corporal were killed. Captain Polson shared almost as hard a fate, for only one of his escaped. In short, the dastardly behavior of the English soldiers exposed all those who were inclined to do their duty to almost certain death. It is imagined (I believe with great justice, too) that two thirds of both killed and wounded received their shots from our own cowardly dogs of soldiers, who gathered themselves into a body, contrary to orders, ten and twelve deep, would then level, fire, and shoot down the men before them.”

[These extracts are taken from the two letters preserved in the Public Record Office, America and West Indies, LXXIV. LXXXII.]

To Orme, Dinwiddie replied:

I read your letter with tears in my eyes; but it gave me much pleasure to see your name at the bottom, and more so when I observed by the postscript that your wound is not dangerous. But pray, dear sir, is it not possible by a second attempt to retrieve the great loss we have sustained? I presume the General’s chariot is at the fort. In it you may come here, and my house is heartily at your command. Pray take care of your valuable health; keep your spirits up, and I doubt not of your recovery. My wife and girls join me in most sincere respects and joy at your being so well, and I always am, with great truth, dear friend, your affectionate humble servant.”

To Washington he is less effusive, though he had known him much longer. He begins, it is true, “Dear Washington,” and congratulates him on his escape; but soon grows formal, and asks: “Pray, sir, with the number of them remaining, is there no possibility of doing something on the other side of the mountains before the winter months? Surely you must mistake. Colonel Dunbar will not march to winter-quarters in the middle of summer, and leave the frontiers exposed to the invasions of the enemy! No; he is a better officer, and I have a different opinion of him. I sincerely wish you health and happiness, and am, with great respect, sir, your obedient, humble servant.”

Washington’s letter had contained the astonishing announcement that Dunbar meant to abandon the frontier and march to Philadelphia. Dinwiddie, much disturbed, at once wrote to that officer, though without betraying any knowledge of his intention. “Sir, the melancholy account of the defeat of our forces gave me a sensible and real concern”–on which he enlarges for a while; then suddenly changes style: “Dear Colonel, is there no method left to retrieve the dishonor done to the British arms? As you now command all the forces that remain, are you not able, after a proper refreshment of your men, to make a second attempt? You have four months now to come of the best weather of the year for such an expedition. What a fine field for honor will Colonel Dunbar have to confirm and establish his character as a brave officer.” Then, after suggesting plans of operation, and entering into much detail, the fervid Governor concludes: “It gives me great pleasure that under our great loss and misfortunes the command devolves on an officer of so great military judgment and established character. With my sincere respect and hearty wishes for success to all your proceedings, I am, worthy sir, your most obedient, humble servant.”

Exhortation and flattery were lost on Dunbar. Dinwiddie received from him in reply a short, dry note, dated on the first of August, and acquainting him that he should march for Philadelphia on the second. This, in fact, he did, leaving the fort to be defended by invalids and a few Virginians. “I acknowledge,” says Dinwiddie, “I was not brought up to arms; but I think common sense would have prevailed not to leave the frontiers exposed after having opened a road over the mountains to the Ohio, by which the enemy can the more easily invade us…. Your great colonel,” he writes to Orme, “is gone to a peaceful colony, and left our frontiers open…. The whole conduct of Colonel Dunbar appears to me monstrous…. To march off all the regulars, and leave the fort and frontiers to be defended by four hundred sick and wounded, and the poor remains of our provincial forces, appears to me absurd.”

[Dinwiddie’s view of Dunbar’s conduct is fully justified by the letters of Shirley, Governor Morris, and Dunbar himself.]

He found some comfort from the burgesses, who gave him forty thousand pounds, and would, he thinks, have given a hundred thousand if another attempt against Fort Duquesne had been set afoot. Shirley, too, whom the death of Braddock had made commander-in-chief, approved the Governor’s plan of renewing offensive operations, and instructed Dunbar to that effect; ordering him, however, should they prove impracticable, to march for Albany in aid of the Niagara expedition. [5] The order found him safe in Philadelphia. Here he lingered for a while; then marched to join the northern army, moving at a pace which made it certain that he could not arrive in time to be of the least use.

[5: Orders for Colonel Thomas Dunbar, 12 Aug. 1755. These supersede a previous order of August 6, by which Shirley had directed Dunbar to march northward at once.]

Thus, the frontier was left unguarded; and soon, as Dinwiddie had foreseen, there burst upon it a storm of blood and fire.

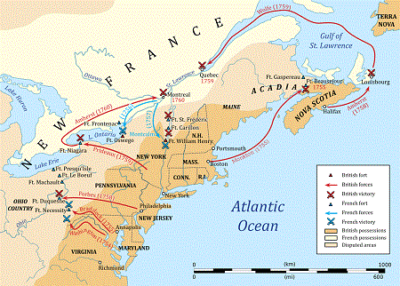

By the plan which the Duke of Cumberland had ordained and Braddock had announced in the Council at Alexandria, four blows were to be struck at once to force back the French boundaries, lop off the dependencies of Canada, and reduce her from a vast territory to a petty province. The first stroke had failed and had shattered the hand of the striker; it remains to see what fortune awaited the others.

It was long since a project of purging Acadia of French influence had germinated in the fertile mind of Shirley. We have seen in a former chapter the condition of that afflicted province. Several thousands of its inhabitants, wrought upon by intriguing agents of the French Government; taught by their priests that fidelity to King Louis was inseparable from fidelity to God, and that to swear allegiance to the British Crown was eternal perdition; threatened with plunder and death at the hands of the savages whom the ferocious missionary, Le Loutre, held over them in terror, — had abandoned, sometimes willingly, but oftener under constraint, the fields which they and their fathers had tilled, and crossing the boundary line of the Missaguash, had placed themselves under the French flag planted on the hill of Beauséjour.[6] Here, or in the neighborhood, many of them had remained, wretched and half starved; while others had been transported to Cape Breton, Isle St. Jean, or the coasts of the Gulf, — not so far, however, that they could not on occasion be used to aid in an invasion of British Acadia. [7] Those of their countrymen who still lived under the British flag were chiefly the inhabitants of the district of Mines and of the valley of the River Annapolis, who, with other less important settlements, numbered a little more than nine thousand souls. We have shown already, by the evidence of the French themselves, that neither they nor their emigrant countrymen had been oppressed or molested in matters temporal or spiritual, but that the English authorities, recognizing their value as an industrious population, had labored to reconcile them to a change of rulers which on the whole was to their advantage. It has been shown also how, with a heartless perfidy and a reckless disregard of their welfare and safety, the French Government and its agents labored to keep them hostile to the Crown of which it had acknowledged them to be subjects. The result was, that though they did not, like their emigrant countrymen, abandon their homes, they remained in a state of restless disaffection, refused to supply English garrisons with provisions, except at most exorbitant rates, smuggled their produce to the French across the line, gave them aid and intelligence, and sometimes, disguised as Indians, robbed and murdered English settlers. By the new-fangled construction of the treaty of Utrecht which the French boundary commissioners had devised, [8] more than half the Acadian peninsula, including nearly all the cultivated land and nearly all the population of French descent, was claimed as belonging to France, though England had held possession of it more than forty years. Hence, according to the political ethics adopted at the time by both nations, it would be lawful for France to reclaim it by force. England, on her part, it will be remembered, claimed vast tracts beyond the isthmus; and, on the same pretext, held that she might rightfully seize them and capture Beauséjour, with the other French garrisons that guarded them.

[6: See ante, Chapter IV.]

[7: Rameau (La France aux Colonies, I. 63), estimates the total emigration from 1748 to 1755 at 8,600 souls,–which number seems much too large. This writer, though vehemently anti-English, gives the following passage from a letter of a high French official: “que les Acadiens émigrés et en grande misère comptaient se retirer à Québec et demander des terres, mais il conviendrait mieux qu’ils restent où ils sont, afin d’avoir le voisinage de l’Acadie bien peuplé et défriché, pour approvisionner l’Isle Royale [Cape Breton] et tomber en cas de guerre sur l’Acadie.” Rameau, I. 133.]

[8: Supra, p. 123.]

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 8 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.