The English spent some days in preparing their camp and reconnoitering the ground.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 8.

This was the state of affairs at Beauséjour while Shirley and Lawrence were planning its destruction. Lawrence had empowered his agent, Monckton, to draw without limit on two Boston merchants, Apthorp and Hancock. Shirley, as commander-in-chief of the province of Massachusetts, commissioned John Winslow to raise two thousand volunteers. Winslow was sprung from the early governors of Plymouth colony; but, though well-born, he was ill-educated, which did not prevent him from being both popular and influential. He had strong military inclinations, had led a company of his own raising in the luckless attack on Carthagena, had commanded the force sent in the preceding summer to occupy the Kennebec, and on various other occasions had left his Marshfield farm to serve his country. The men enlisted readily at his call, and were formed into a regiment, of which Shirley made himself the nominal colonel. It had two battalions, of which Winslow, as lieutenant-colonel, commanded the first, and George Scott the second, both under the orders of Monckton. Country villages far and near, from the western borders of the Connecticut to uttermost Cape Cod, lent soldiers to the new regiment. The muster-rolls preserve their names, vocations, birthplaces, and abode. Obadiah, Nehemiah, Jedediah, Jonathan, Ebenezer, Joshua, and the like Old Testament names abound upon the list. Some are set down as “farmers,” “yeomen,” or “husbandmen;” others as “shopkeepers,” others as “fishermen,” and many as “laborers;” while a great number were handicraftsmen of various trades, from blacksmiths to wig-makers. They mustered at Boston early in April, where clothing, haversacks, and blankets were served out to them at the charge of the King; and the crooked streets of the New England capital were filled with staring young rustics. On the next Saturday the following mandate went forth: “The men will behave very orderly on the Sabbath Day, and either stay on board their transports, or else go to church, and not stroll up and down the streets.” The transports, consisting of about forty sloops and schooners, lay at Long Wharf; and here on Monday a grand review took place, — to the gratification, no doubt, of a populace whose amusements were few. All was ready except the muskets, which were expected from England, but did not come. Hence the delay of a month, threatening to ruin the enterprise. When Shirley returned from Alexandria he found, to his disgust, that the transports still lay at the wharf where he had left them on his departure. [1] The muskets arrived at length, and the fleet sailed on the twenty-second of May. Three small frigates, the “Success,” the “Mermaid,” and the “Siren,” commanded by the ex-privateersman, Captain Rous, acted as convoy; and on the twenty-sixth the whole force safely reached Annapolis. Thence after some delay they sailed up the Bay of Fundy, and at sunset on the first of June anchored within five miles of the hill of Beauséjour.

[1: Shirley to Robinson, 20 June, 1755.]

At two o’clock on the next morning a party of Acadians from Chipody roused Vergor with the news. In great alarm, he sent a messenger to Louisbourg to beg for help and ordered all the fighting men of the neighborhood to repair to the fort. They counted in all between twelve and fifteen hundred; [2] but they had no appetite for war. The force of the invaders daunted them; and the hundred and sixty regulars who formed the garrison of Beauséjour were too few to revive their confidence. Those of them who had crossed from the English side dreaded what might ensue should they be caught in arms; and, to prepare an excuse beforehand, they begged Vergor to threaten them with punishment if they disobeyed his order. He willingly complied, promised to have them killed if they did not fight, and assured them at the same time that the English could never take the fort. [3] Three hundred of them thereupon joined the garrison, and the rest, hiding their families in the woods, prepared to wage guerilla war against the invaders.

[2: Mémoires sur le Canada, 1749-1760. An English document, State of the English and French Forts in Nova Scotia, says 1,200 to 1,400.]

[3: Mémoires sur le Canada, 1749-1760.]

Monckton, with all his force, landed unopposed, and encamped at night on the fields around Fort Lawrence, whence he could contemplate Fort Beauséjour at his ease. The regulars of the English garrison joined the New England men; and then, on the morning of the fourth, they marched to the attack. Their course lay along the south bank of the Missaguash to where it was crossed by a bridge called Pont-à-Buot. This bridge had been destroyed; and on the farther bank there was a large blockhouse and a breastwork of timber defended by four hundred regulars, Acadians, and Indians. They lay silent and unseen till the head of the column reached the opposite bank; then raised a yell and opened fire, causing some loss. Three field-pieces were brought up, the defenders were driven out, and a bridge was laid under a spattering fusillade from behind bushes, which continued till the English had crossed the stream. Without further opposition, they marched along the road to Beauséjour, and, turning to the right, encamped among the woody hills half a league from the fort. That night there was a grand illumination, for Vergor set fire to the church and all the houses outside the ramparts.

[Winslow, Journal and Letter Book. Mémoires sur le Canada, 1749-1760. Letters from officers on the spot in Boston Evening Post and Boston News Letter. Journal of Surgeon John Thomas.]

Captain Rous, on board his ship in the harbor, watched the bombardment with great interest. Having occasion to write to Winslow, he closed his letter in a facetious strain. “I often hear of your success in plunder, particularly a coach. [4] I hope you have some fine horses for it, at least four, to draw it, that it may be said a New England colonel [rode in] his coach and four in Nova Scotia. If you have any good saddle-horses in your stable, I should be obliged to you for one to ride round the ship’s deck on for exercise, for I am not likely to have any other.”

[4: “11 June. Capt. Adams went with a Company of Raingers, and Returned at 11 Clock with a Coach and Sum other Plunder.” Journal of John Thomas.]

Within the fort there was little promise of a strong defense. Le Loutre, it is true, was to be seen in his shirt-sleeves, with a pipe in his mouth, directing the Acadians in their work of strengthening the fortifications. [5] They, on their part, thought more of escape than of fighting. Some of them vainly begged to be allowed to go home; others went off without leave, — which was not difficult, as only one side of the place was attacked. Even among the officers there were some in whom interest was stronger than honor, and who would rather rob the King than die for him. The general discouragement was redoubled when, on the fourteenth, a letter came from the commandant of Louisbourg to say that he could send no help, as British ships blocked the way. On the morning of the sixteenth, a mischance befell, recorded in these words in the diary of Surgeon John Thomas: “One of our large shells fell through what they called their bomb-proof, where a number of their officers were sitting, killed six of them dead, and one Ensign Hay, which the Indians had took prisoner a few days agone and carried to the fort.” The party was at breakfast when the unwelcome visitor burst in. Just opposite was a second bomb-proof, where was Vergor himself, with Le Loutre, another priest, and several officers, who felt that they might at any time share the same fate. The effect was immediate. The English, who had not yet got a single cannon into position, saw to their surprise a white flag raised on the rampart. Some officers of the garrison protested against surrender; and Le Loutre, who thought that he had everything to fear at the hands of the victors, exclaimed that it was better to be buried under the ruins of the fort than to give it up; but all was in vain, and the valiant Vannes was sent out to propose terms of capitulation. They were rejected, and others offered, to the following effect: the garrison to march out with the honors of war and to be sent to Louisbourg at the charge of the King of England, but not to bear arms in America for the space of six months. The Acadians to be pardoned the part they had just borne in the defense, “seeing that they had been compelled to take arms on pain of death.” Confusion reigned all day at Beauséjour. The Acadians went home loaded with plunder. The French officers were so busy in drinking and pillaging that they could hardly be got away to sign the capitulation. At the appointed hour, seven in the evening, Scott marched in with a body of provincials, raised the British flag on the ramparts, and saluted it by a general discharge of the French cannon, while Vergor as a last act of hospitality gave a supper to the officers. [6]

[5: Journal of Pichon, cited by Beamish Murdoch.]

[6: On the capture of Beauséjour, Mémoires sur le Canada, 1749-1760; Pichon, Cape Breton, 318; Journal of Pichon, cited by Murdoch; and the English accounts already mentioned.]

Le Loutre was not to be found; he had escaped in disguise with his box of papers, and fled to Baye Verte to join his brother missionary, Manach. Thence he made his way to Quebec, where the Bishop received him with reproaches. He soon embarked for France; but the English captured him on the way, and kept him eight years in Elizabeth Castle, on the Island of Jersey. Here on one occasion a soldier on guard made a dash at the father, tried to stab him with his bayonet, and was prevented with great difficulty. He declared that, when he was with his regiment in Acadia, he had fallen into the hands of Le Loutre, and narrowly escaped being scalped alive, the missionary having doomed him to this fate, and with his own hand drawn a knife round his head as a beginning of the operation. The man swore so fiercely that he would have his revenge, that the officer in command transferred him to another post.

[Knox, Campaigns in North America, I. 114, note. Knox, who was stationed in Nova Scotia, says that Le Loutre left behind him “a most remarkable character for inhumanity.”]

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 8 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

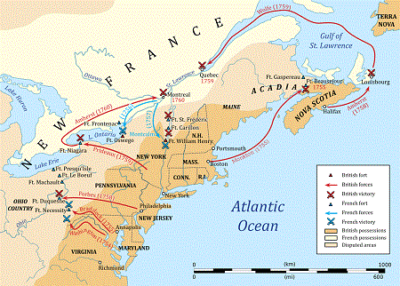

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.