A powerful ally presently came to his aid in the shape of Benjamin Franklin, then postmaster-general of Pennsylvania.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 7.

The plans against Crown Point and Beauséjour had already found the approval of the Home Government and the energetic support of all the New England colonies. Preparation for them was in full activity; and it was with great difficulty that Shirley had disengaged himself from these cares to attend the council at Alexandria. He and Dinwiddie stood in the front of opposition to French designs. As they both defended the royal prerogative and were strong advocates of taxation by Parliament, they have found scant justice from American writers. Yet the British colonies owed them a debt of gratitude, and the American States owe it still.

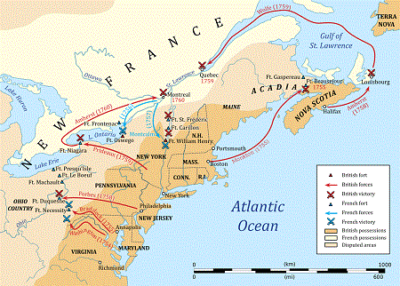

Braddock, laid his instructions before the Council, and Shirley found them entirely to his mind; while the General, on his part, fully approved the schemes of the Governor. The plan of the campaign was settled. The French were to be attacked at four points at once. The two British regiments lately arrived were to advance on Fort Duquesne; two new regiments, known as Shirley’s and Pepperell’s, just raised in the provinces, and taken into the King’s pay, were to reduce Niagara; a body of provincials from New England, New York, and New Jersey was to seize Crown Point; and another body of New England men to capture Beauséjour and bring Acadia to complete subjection. Braddock himself was to lead the expedition against Fort Duquesne. He asked Shirley, who, though a soldier only in theory, had held the rank of colonel since the last war, to charge himself with that against Niagara; and Shirley eagerly assented. The movement on Crown Point was intrusted to Colonel William Johnson, by reason of his influence over the Indians and his reputation for energy, capacity, and faithfulness. Lastly, the Acadian enterprise was assigned to Lieutenant-Colonel Monckton, a regular officer of merit.

To strike this fourfold blow in time of peace was a scheme worthy of Newcastle and of Cumberland. The pretext was that the positions to be attacked were all on British soil; that in occupying them the French had been guilty of invasion; and that to expel the invaders would be an act of self-defence. Yet in regard to two of these positions, the French, if they had no other right, might at least claim one of prescription. Crown Point had been twenty-four years in their undisturbed possession, while it was three quarters of a century since they first occupied Niagara; and, though New York claimed the ground, no serious attempt had been made to dislodge them.

Other matters now engaged the Council. Braddock, in accordance with his instructions, asked the governors to urge upon their several assemblies the establishment of a general fund for the service of the campaign; but the governors were all of opinion that the assemblies would refuse,— each being resolved to keep the control of its money in its own hands; and all present, with one voice, advised that the colonies should be compelled by Act of Parliament to contribute in due proportion to the support of the war. Braddock next asked if, in the judgment of the Council, it would not be well to send Colonel Johnson with full powers to treat with the Five Nations, who had been driven to the verge of an outbreak by the misconduct of the Dutch Indian commissioners at Albany. The measure was cordially approved, as was also another suggestion of the General, that vessels should be built at Oswego to command Lake Ontario. The Council then dissolved.

Shirley hastened back to New England, burdened with the preparation for three expeditions and the command of one of them. Johnson, who had been in the camp, though not in the Council, went back to Albany, provided with a commission as sole superintendent of Indian affairs, and charged, besides, with the enterprise against Crown Point; while an express was dispatched to Monckton at Halifax, with orders to set at once to his work of capturing Beauséjour.

[Minutes of a Council held at the Camp at Alexandria, in Virginia, April 14, 1755. Instructions to Major-General Braddock, 25 Nov. 1754. Secret Instructions to Major-General Braddock, same date. Napier to Braddock, written by Order of the Duke of Cumberland, 25 Nov. 1754, in Précis des Faits, Pièces justificatives, 168. Orme, Journal of Braddock’s Expedition. Instructions to Governor Shirley. Correspondence of Shirley. Correspondence of Braddock (Public Record Office). Johnson Papers. Dinwiddie Papers. Pennsylvania Archives, II.]

In regard to Braddock’s part of the campaign, there had been a serious error. If, instead of landing in Virginia and moving on Fort Duquesne by the long and circuitous route of Wills Creek, the two regiments had disembarked at Philadelphia and marched westward, the way would have been shortened, and would have lain through one of the richest and most populous districts on the continent, filled with supplies of every kind. In Virginia, on the other hand, and in the adjoining province of Maryland, wagons, horses, and forage were scarce. The enemies of the Administration ascribed this blunder to the influence of the Quaker merchant, John Hanbury, whom the Duke of Newcastle had consulted as a person familiar with American affairs. Hanbury, who was a prominent stockholder in the Ohio Company, and who traded largely in Virginia, saw it for his interest that the troops should pass that way; and is said to have brought the Duke to this opinion. [1] A writer of the time thinks that if they had landed in Pennsylvania, forty thousand pounds would have been saved in money, and six weeks in time. [2]

[1: Shebbeare’s Tracts, Letter I. Dr. Shebbeare was a political pamphleteer, pilloried by one ministry, and rewarded by the next. He certainly speaks of Hanbury, though he does not give his name. Compare Sargent, 107, 162.]

[2: Gentleman’s Magazine, Aug. 1755.]

Not only were supplies scarce, but the people showed such unwillingness to furnish them, and such apathy in aiding the expedition, that even Washington was provoked to declare that “they ought to be chastised.” [3] Many of them thought that the alarm about French encroachment was a device of designing politicians; and they did not awake to a full consciousness of the peril till it was forced upon them by a deluge of calamities, produced by the purblind folly of their own representatives, who, instead of frankly promoting the expedition, displayed a perverse and exasperating narrowness which chafed Braddock to fury. He praises the New England colonies, and echoes Dinwiddie’s declaration that they have shown a “fine martial spirit,” and he commends Virginia as having done far better than her neighbors; but for Pennsylvania he finds no words to express his wrath. [4] He knew nothing of the intestine war between proprietaries and people, and hence could see no palliation for a conduct which threatened to ruin both the expedition and the colony. Everything depended on speed, and speed was impossible; for stores and provisions were not ready, though notice to furnish them had been given months before. The quartermaster-general, Sir John Sinclair, “stormed like a lion rampant,” but with small effect. [5] Contracts broken or disavowed, want of horses, want of wagons, want of forage, want of wholesome food, or sufficient food of any kind, caused such delay that the report of it reached England, and drew from Walpole the comment that Braddock was in no hurry to be scalped. In reality he was maddened with impatience and vexation.

[3: Writings of Washington, II. 78. He speaks of the people of Pennsylvania.]

[4: Braddock to Robinson, 18 March, 19 April, 5 June, 1755, etc. On the attitude of Pennsylvania, Colonial Records of Pa., VI., passim.]

[5: Colonial Records of Pa., VI. 368.]

A powerful ally presently came to his aid in the shape of Benjamin Franklin, then postmaster-general of Pennsylvania. That sagacious personage,–the sublime of common-sense, about equal in his instincts and motives of character to the respectable average of the New England that produced him, but gifted with a versatile power of brain rarely matched on earth,–was then divided between his strong desire to repel a danger of which he saw the imminence, and his equally strong antagonism to the selfish claims of the Penns, proprietaries of Pennsylvania. This last motive had determined his attitude towards their representative, the Governor, and led him into an opposition as injurious to the military good name of the province as it was favorable to its political longings. In the present case there was no such conflict of inclinations; he could help Braddock without hurting Pennsylvania. He and his son had visited the camp, and found the General waiting restlessly for the report of the agents whom he had sent to collect wagons. “I stayed with him,” says Franklin, “several days, and dined with him daily. When I was about to depart, the returns of wagons to be obtained were brought in, by which it appeared that they amounted only to twenty-five, and not all of these were in serviceable condition.” On this the General and his officers declared that the expedition was at an end, and denounced the Ministry for sending them into a country void of the means of transportation. Franklin remarked that it was a pity they had not landed in Pennsylvania, where almost every farmer had his wagon. Braddock caught eagerly at his words, and begged that he would use his influence to enable the troops to move. Franklin went back to Pennsylvania, issued an address to the farmers appealing to their interest and their fears, and in a fortnight procured a hundred and fifty wagons, with a large number of horses. [6] Braddock, grateful to his benefactor, and enraged at everybody else, pronounced him “Almost the only instance of ability and honesty I have known in these provinces.” [7] More wagons and more horses gradually arrived, and at the eleventh hour the march began.

[6: Franklin, Autobiography. Advertisement of B. Franklin for Wagons; Address to the Inhabitants of the Counties of York, Lancaster, and Cumberland, in Pennsylvania Archives, II. 294.]

[7: Braddock to Robinson, 5 June, 1755. The letters of Braddock here cited are the originals in the Public Record Office.]

On the tenth of May Braddock reached Wills Creek, where the whole force was now gathered, having marched thither by detachments along the banks of the Potomac. This old trading-station of the Ohio Company had been transformed into a military post and named Fort Cumberland. During the past winter the independent companies which had failed Washington in his need had been at work here to prepare a base of operations for Braddock. Their axes had been of more avail than their muskets. A broad wound had been cut in the bosom of the forest, and the murdered oaks and chestnuts turned into ramparts, barracks, and magazines. Fort Cumberland was an enclosure of logs set upright in the ground, pierced with loopholes, and armed with ten small cannon. It stood on a rising ground near the point where Wills Creek joined the Potomac, and the forest girded it like a mighty hedge, or rather like a paling of gaunt brown stems upholding a canopy of green. All around spread illimitable woods, wrapping hill, valley, and mountain. The spot was an oasis in a desert of leaves, — if the name oasis can be given to anything so rude and harsh. In this rugged area, or “clearing,” all Braddock’s force was now assembled, amounting, regulars, provincials, and sailors, to about twenty-two hundred men. The two regiments, Halket’s and Dunbar’s, had been completed by enlistment in Virginia to seven hundred men each. Of Virginians there were nine companies of fifty men, who found no favor in the eyes of Braddock or his officers. To Ensign Allen of Halket’s regiment was assigned the duty of “making them as much like soldiers as possible.” [8] — that is, of drilling them like regulars. The General had little hope of them, and informed Sir Thomas Robinson that “their slothful and languid disposition renders them very unfit for military service,”–a point on which he lived to change his mind. Thirty sailors, whom Commodore Keppel had lent him, were more to his liking, and were in fact of value in many ways. He had now about six hundred baggage-horses, besides those of the artillery, all weakening daily on their diet of leaves; for no grass was to be found. There was great show of discipline, and little real order. Braddock’s executive capacity seems to have been moderate, and his dogged, imperious temper, rasped by disappointments, was in constant irritation. “He looks upon the country, I believe,” writes Washington, “as void of honor or honesty. We have frequent disputes on this head, which are maintained with warmth on both sides, especially on his, as he is incapable of arguing without it, or giving up any point he asserts, be it ever so incompatible with reason or common sense.” [9] Braddock’s secretary, the younger Shirley, writing to his friend Governor Morris, spoke thus irreverently of his chief: “As the King said of a neighboring governor of yours [Sharpe], when proposed for the command of the American forces about a twelvemonth ago, and recommended as a very honest man, though not remarkably able, ‘a little more ability and a little less honesty upon the present occasion might serve our turn better.’ It is a joke to suppose that secondary officers can make amends for the defects of the first; the mainspring must be the mover. As to the others, I don’t think we have much to boast; some are insolent and ignorant, others capable, but rather aiming at showing their own abilities than making a proper use of them. I have a very great love for my friend Orme, and think it uncommonly fortunate for our leader that he is under the influence of so honest and capable a man; but I wish for the sake of the public he had some more experience of business, particularly in America. I am greatly disgusted at seeing an expedition (as it is called), so ill-concerted originally in England, so improperly conducted since in America.” [10]

[8: Orme, Journal.]

[9: Writings of Washington, II. 77.]

[10 Shirley the younger to Morris, 23 May, 1755, in Colonial Records of Pa., VI. 404.]

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 7 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.