Virginia and all the British colonies owed him much; for, though past sixty, he was the most watchful sentinel against French aggression and its most strenuous opponent.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 5.

After leaving Venango on his return, he found the horses so weak that, to arrive the sooner, he left them and their drivers in charge of Vanbraam and pushed forward on foot, accompanied by Gist alone. Each was wrapped to the throat in an Indian “matchcoat,” with a gun in his hand and a pack at his back. Passing an old Indian hamlet called Murdering Town, they had an adventure which threatened to make good the name. A French Indian, whom they met in the forest, fired at them, pretending that his gun had gone off by chance. They caught him, and Gist would have killed him; but Washington interposed, and they let him go. [1] Then, to escape pursuit from his tribesmen, they walked all night and all the next day. This brought them to the banks of the Alleghany. They hoped to have found it dead frozen; but it was all alive and turbulent, filled with ice sweeping down the current. They made a raft, shoved out into the stream, and were soon caught helplessly in the drifting ice. Washington, pushing hard with his setting-pole, was jerked into the freezing river; but caught a log of the raft, and dragged himself out. By no efforts could they reach the farther bank, or regain that which they had left; but they were driven against an island, where they landed, and left the raft to its fate. The night was excessively cold, and Gist’s feet and hands were badly frost-bitten. In the morning, the ice had set, and the river was a solid floor. They crossed it, and succeeded in reaching the house of the trader Fraser, on the Monongahela. It was the middle of January when Washington arrived at Williamsburg and made his report to Dinwiddie.

[1. Journal of Mr. Christopher Gist, in Mass. Hist. Coll., 3rd Series, V.]

Robert Dinwiddie was lieutenant-governor of Virginia, in place of the titular governor, Lord Albemarle, whose post was a sinecure. He had been clerk in a government office in the West Indies; then surveyor of customs in the “Old Dominion,” — a position in which he made himself cordially disliked; and when he rose to the governorship he carried his unpopularity with him. Yet Virginia and all the British colonies owed him much; for, though past sixty, he was the most watchful sentinel against French aggression and its most strenuous opponent. Scarcely had Marin’s vanguard appeared at Presquisle, when Dinwiddie warned the Home Government of the danger, and urged, what he had before urged in vain on the Virginian Assembly, the immediate building of forts on the Ohio. There came in reply a letter, signed by the King, authorizing him to build the forts at the cost of the Colony, and to repel force by force in case he was molested or obstructed. Moreover, the King wrote, “If you shall find that any number of persons shall presume to erect any fort or forts within the limits of our province of Virginia, you are first to require of them peaceably to depart; and if, notwithstanding your admonitions, they do still endeavor to carry out any such unlawful and unjustifiable designs, we do hereby strictly charge and command you to drive them off by force of arms.”

[Instructions to Our Trusty and Well-beloved Robert Dinwiddie, Esq., 28 Aug. 1753.]

The order was easily given; but to obey it needed men and money, and for these Dinwiddie was dependent on his Assembly, or House of Burgesses. He convoked them for the first of November, sending Washington at the same time with the summons to Saint-Pierre. The burgesses met. Dinwiddie exposed the danger, and asked for means to meet it. [2] They seemed more than willing to comply; but debates presently arose concerning the fee of a pistole, which the Governor had demanded on each patent of land issued by him. The amount was trifling, but the principle was doubtful. The aristocratic republic of Virginia was intensely jealous of the slightest encroachment on its rights by the Crown or its representative. The Governor defended the fee. The burgesses replied that “subjects cannot be deprived of the least part of their property without their consent,” declared the fee unlawful, and called on Dinwiddie to confess it to be so. He still defended it. They saw in his demand for supplies a means of bringing him to terms, and refused to grant money unless he would recede from his position. Dinwiddie rebuked them for “disregarding the designs of the French, and disputing the rights of the Crown”; and he “prorogued them in some anger.” [3]

[2. Address of Lieutenant-Governor Dinwiddie to the Council and Burgesses, 1 Nov. 1753.]

[3. Dinwiddie Papers.]

Thus, he was unable to obey the instructions of the King. As a temporary resource, he ventured to order a draft of two hundred men from the militia. Washington was to have command, with the trader, William Trent, as his lieutenant. His orders were to push with all speed to the forks of the Ohio, and there build a fort; “but in case any attempts are made to obstruct the works by any persons whatsoever, to restrain all such offenders, and, in case of resistance, to make prisoners of, or kill and destroy them.” [4] The Governor next sent messengers to the Catawbas, Cherokees, Chickasaws, and Iroquois of the Ohio, inviting them to take up the hatchet against the French, “who, under pretense of embracing you, mean to squeeze you to death.” Then he wrote urgent letters to the governors of Pennsylvania, the Carolinas, Maryland, and New Jersey, begging for contingents of men, to be at Wills Creek in March at the latest. But nothing could be done without money; and trusting for a change of heart on the part of the burgesses, he summoned them to meet again on the fourteenth of February. “If they come in good temper,” he wrote to Lord Fairfax, a nobleman settled in the colony, “I hope they will lay a fund to qualify me to send four or five hundred men more to the Ohio, which, with the assistance of our neighboring colonies, may make some figure.”

[4. Ibid. Instructions to Major George Washington, January, 1754.]

The session began. Again, somewhat oddly, yet forcibly, the Governor set before the Assembly the peril of the situation and begged them to postpone less pressing questions to the exigency of the hour. [5] This time they listened; and voted ten thousand pounds in Virginia currency to defend the frontier. The grant was frugal, and they jealously placed its expenditure in the hands of a committee of their own. [6] Dinwiddie, writing to the Lords of Trade, pleads necessity as his excuse for submitting to their terms. “I am sorry,” he says, “to find them too much in a republican way of thinking.” What vexed him still more was their sending an agent to England to complain against him on the irrepressible question of the pistole fee; and he writes to his London friend, the merchant Hanbury:

I have had a great deal of trouble from the factious disputes and violent heats of a most impudent, troublesome party here in regard to that silly fee of a pistole. Surely every thinking man will make a distinction between a fee and a tax. Poor people! I pity their ignorance and narrow, ill-natured spirits. But, my friend, consider that I could by no means give up this fee without affronting the Board of Trade and the Council here who established it.”

His thoughts were not all of this harassing nature, and he ends his letter with the following petition:

Now sir, as His Majesty is pleased to make me a military officer, please send for Scott, my tailor, to make me a proper suit of regimentals, to be here by His Majesty’s birthday. I do not much like gayety in dress, but I conceive this necessary. I do not much care for lace on the coat, but a neat embroidered button-hole; though you do not deal that way, I know you have a good taste, that I may show my friend’s fancy in that suit of clothes; a good laced hat and two pair stockings, one silk, the other fine thread.” [7]

[5. Speech of Lieutenant-Governor Dinwiddie to the Council and Burgesses 14 Feb., 1754.]

[6. See the bill in Hening, Statutes of Virginia, VI. 417.]

[7. Dinwiddie to Hanbury, 12 March, 1754; Ibid., 10 May, 1754.]

If the Governor and his English sometimes provoke a smile, he deserves admiration for the energy with which he opposed the public enemy, under circumstances the most discouraging. He invited the Indians to meet him in council at Winchester, and, as bait to attract them, coupled the message with a promise of gifts. He sent circulars from the King to the neighboring governors, calling for supplies, and wrote letter upon letter to rouse them to effort. He wrote also to the more distant governors, Delancey of New York, and Shirley of Massachusetts, begging them to make what he called a “faint” against Canada, to prevent the French from sending so large a force to the Ohio. It was to the nearer colonies, from New Jersey to South Carolina, that he looked for direct aid; and their several governors were all more or less active to procure it; but as most of them had some standing dispute with their assemblies, they could get nothing except on terms with which they would not, and sometimes could not, comply. As the lands invaded by the French belonged to one of the two rival claimants, Virginia and Pennsylvania, the other colonies had no mind to vote money to defend them. Pennsylvania herself refused to move. Hamilton, her governor, could do nothing against the placid obstinacy of the Quaker non-combatants and the stolid obstinacy of the German farmers who chiefly made up his Assembly. North Carolina alone answered the appeal and gave money enough to raise three or four hundred men. Two independent companies maintained by the King in New York, and one in South Carolina, had received orders from England to march to the scene of action; and in these, with the scanty levies of his own and the adjacent province, lay Dinwiddie’s only hope. With men abundant and willing, there were no means to put them into the field, and no commander whom they would all obey.

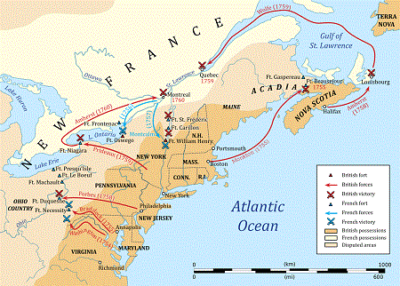

From the brick house at Williamsburg pompously called the Governor’s Palace, Dinwiddie dispatched letters, orders, couriers, to hasten the tardy reinforcements of North Carolina and New York, and push on the raw soldiers of the Old Dominion, who now numbered three hundred men. They were called the Virginia regiment; and Joshua Fry, an English gentleman, bred at Oxford, was made their colonel, with Washington as next in command. Fry was at Alexandria with half the so-called regiment, trying to get it into marching order; Washington, with the other half, had pushed forward to the Ohio Company’s storehouse at Wills Creek, which was to form a base of operations. His men were poor whites, brave, but hard to discipline; without tents, ill armed, and ragged as Falstaff’s recruits. Besides these, a band of backwoodsmen under Captain Trent had crossed the mountains in February to build a fort at the forks of the Ohio, where Pittsburg now stands, — a spot which Washington had examined when on his way to Fort Le Boeuf, and which he had reported as the best for the purpose. The hope was that Trent would fortify himself before the arrival of the French, and that Washington and Fry would join him in time to secure the position. Trent had begun the fort; but for some unexplained reason had gone back to Wills Creek, leaving Ensign Ward with forty men at work upon it. Their labors were suddenly interrupted. On the seventeenth of April a swarm of bateaux and canoes came down the Alleghany, bringing, according to Ward, more than a thousand Frenchmen, though in reality not much above five hundred, who landed, planted cannon against the incipient stockade, and summoned the ensign to surrender, on pain of what might ensue. [8] He complied and was allowed to depart with his men. Retracing his steps over the mountains, he reported his mishap to Washington; while the French demolished his unfinished fort, began a much larger and better one, and named it Fort Duquesne.

[8. See the summons in Précis des Faits, 101.]

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 5 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.