Buried in the wilderness, the military exiles resigned themselves as they might to months of monotonous solitude; when, just after sunset on the eleventh of December, a tall youth came out of the forest on horseback.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 4.

The commissioners at Paris broke up their sessions, leaving as the monument of their toils four quarto volumes of allegations, arguments, and documentary proofs. [1] Out of the discussion rose also a swarm of fugitive publications in French, English, and Spanish; for the question of American boundaries had become European. There was one among them worth notice from its amusing absurdity. It is an elaborate disquisition, under the title of Roman politique, by an author faithful to the traditions of European diplomacy and inspired at the same time by the new philosophy of the school of Rousseau. He insists that the balance of power must be preserved in America as well as in Europe, because “Nature,” “the aggrandizement of the human soul,” and the “felicity of man” are unanimous in demanding it. The English colonies are more populous and wealthy than the French; therefore, the French should have more land, to keep the balance. Nature, the human soul, and the felicity of man require that France should own all the country beyond the Alleghanies and all Acadia but a strip of the south coast, according to the “sublime negotiations” of the French commissioners, of which the writer declares himself a “religious admirer.” [2]

[1. Mémoires des Commissaires de Sa Majesté Très Chrétienne et de ceux de Sa Majesté Brittanique. Paris, 1755. Several editions appeared.]

[2. Roman politique sur l’État présent des Affaires de l’Amérique (Amsterdam, 1756). For extracts from French Documents]

We know already that France had used means sharper than negotiation to vindicate her claim to the interior of the continent; had marched to the sources of the Ohio to entrench herself there and hold the passes of the West against all comers. It remains to see how she fared in her bold enterprise.

Towards the end of spring the vanguard of the expedition sent by Duquesne to occupy the Ohio landed at Presquisle, where Erie now stands. This route to the Ohio, far better than that which Céloron had followed, was a new discovery to the French; and Duquesne calls the harbor “the finest in nature.” Here they built a fort of squared chestnut logs, and when it was finished they cut a road of several leagues through the woods to Rivière aux Boeufs, now French Creek. At the farther end of this road they began another wooden fort and called it Fort Le Boeuf. Thence, when the water was high, they could descend French Creek to the Allegheny, and follow that stream to the main current of the Ohio.

It was heavy work to carry the cumbrous load of baggage across the portages. Much of it is said to have been superfluous, consisting of velvets, silks, and other useless and costly articles, sold to the King at enormous prices as necessaries of the expedition. [3] The weight of the task fell on the Canadians, who worked with cheerful hardihood, and did their part to admiration. Marin, commander of the expedition, a gruff, choleric old man of sixty-three, but full of force and capacity, spared himself so little that he was struck down with dysentery, and, refusing to be sent home to Montreal, was before long in a dying state. His place was taken by Péan, of whose private character there is little good to be said, but whose conduct as an officer was such that Duquesne calls him a prodigy of talents, resources, and zeal. [4] The subalterns deserve no such praise. They disliked the service and made no secret of their discontent. Rumors of it filled Montreal; and Duquesne wrote to Marin: “I am surprised that you have not told me of this change. Take note of the sullen and discouraged faces about you. This sort are worse than useless. Rid yourself of them at once; send them to Montreal, that I may make an example of them.” [5] Péan wrote at the end of September that Marin was in extremity; and the Governor, disturbed and alarmed, for he knew the value of the sturdy old officer, looked anxiously for a successor. He chose another veteran, Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, who had just returned from a journey of exploration towards the Rocky Mountains, [6] and whom Duquesne now ordered to the Ohio.

[3. Pouchot, Mémoires sur la dernière Guerre de l’Amérique Septentrionale, I. 8.]

[4. Duquesne au Ministre, 2 Nov. 1753; compare Mémoire pour Michel-Jean Hugues Péan.]

[5. Duquesne à Marin, 27 Août, 1753.]

[6. Mémoire ou Journal sommaire du Voyage de Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre.]

Meanwhile the effects of the expedition had already justified it. At first the Indians of the Ohio had shown a bold front. One of them, a chief whom the English called the Half-King, came to Fort Le Bœuf and ordered the French to leave the country; but was received by Marin with such contemptuous haughtiness that he went home shedding tears of rage and mortification. The Western tribes were daunted. The Miamis, but yesterday fast friends of the English, made humble submission to the French, and offered them two English scalps to signalize their repentance; while the Sacs, Pottawattamies, and Ojibwas were loud in professions of devotion. [7] Even the Iroquois, Delawares, and Shawanoes on the Alleghany had come to the French camp and offered their help in carrying the baggage. It needed but perseverance and success in the enterprise to win over every tribe from the mountains to the Mississippi. To accomplish this and to curb the English, Duquesne had planned a third fort, at the junction of French Creek with the Alleghany, or at some point lower down; then, leaving the three posts well garrisoned, Péan was to descend the Ohio with the whole remaining force, impose terror on the wavering tribes, and complete their conversion. Both plans were thwarted; the fort was not built, nor did Péan descend the Ohio. Fevers, lung diseases, and scurvy made such deadly havoc among troops and Canadians, that the dying Marin saw with bitterness that his work must be left half done. Three hundred of the best men were kept to garrison Forts Presquisle and Le Bœuf; and then, as winter approached, the rest were sent back to Montreal. When they arrived, the Governor was shocked at their altered looks. “I reviewed them, and could not help being touched by the pitiable state to which fatigues and exposures had reduced them. Past all doubt, if these emaciated figures had gone down the Ohio as intended, the river would have been strewn with corpses, and the evil-disposed savages would not have failed to attack the survivors, seeing that they were but spectres.” [8]

[7. Rapports de Conseils avec les Sauvages à Montreal, Juillet, 1753. Duquesne au Ministre, 31 Oct. 1753. Letter of Dr. Shuckburgh in N. Y. Col. Docs., VI. 806.]

[8. Duquesne au Ministre, 29 Nov. 1753. On this expedition, compare the letter of Duquesne in N. Y. Col. Docs., X. 255, and the deposition of Stephen Coffen, Ibid., VI. 835.]

Legardeur de Saint-Pierre arrived at the end of autumn, and made his quarters at Fort Le Boeuf. The surrounding forests had dropped their leaves, and in gray and patient desolation bided the coming winter. Chill rains drizzled over the gloomy “clearing,” and drenched the palisades and log-built barracks, raw from the axe. Buried in the wilderness, the military exiles resigned themselves as they might to months of monotonous solitude; when, just after sunset on the eleventh of December, a tall youth came out of the forest on horseback, attended by a companion much older and rougher than himself, and followed by several Indians and four or five white men with packhorses. Officers from the fort went out to meet the strangers; and, wading through mud and sodden snow, they entered at the gate. On the next day the young leader of the party, with the help of an interpreter, for he spoke no French, had an interview with the commandant, and gave him a letter from Governor Dinwiddie. Saint-Pierre and the officer next in rank, who knew a little English, took it to another room to study it at their ease; and in it, all unconsciously, they read a name destined to stand one of the noblest in the annals of mankind; for it introduced Major George Washington, Adjutant-General of the Virginia militia.

[Journal of Major Washington. Journal of Mr. Christopher Gist.]

Dinwiddie, jealously watchful of French aggression, had learned through traders and Indians that a strong detachment from Canada had entered the territories of the King of England, and built forts on Lake Erie and on a branch of the Ohio. He wrote to challenge the invasion and summon the invaders to withdraw; and he could find none so fit to bear his message as a young man of twenty-one. It was this rough Scotchman who launched Washington on his illustrious career.

Washington set out for the trading station of the Ohio Company on Will’s Creek; and thence, at the middle of November, struck into the wilderness with Christopher Gist as a guide, Vanbraam, a Dutchman, as French interpreter, Davison, a trader, as Indian interpreter, and four woodsmen as servants. They went to the forks of the Ohio, and then down the river to Logstown, the Chiningué of Céloron de Bienville. There Washington had various parleys with the Indians; and thence, after vexatious delays, he continued his journey towards Fort Le Boeuf, accompanied by the friendly chief called the Half-King and by three of his tribesmen. For several days they followed the traders’ path, pelted with unceasing rain and snow, and came at last to the old Indian town of Venango, where French Creek enters the Alleghany. Here there was an English trading-house; but the French had seized it, raised their flag over it, and turned it into a military outpost. [9] Joncaire was in command, with two subalterns; and nothing could exceed their civility. They invited the strangers to supper; and, says Washington,

the wine, as they dosed themselves pretty plentifully with it, soon banished the restraint which at first appeared in their conversation, and gave a license to their tongues to reveal their sentiments more freely. They told me that it was their absolute design to take possession of the Ohio, and, by G—-, they would do it; for that although they were sensible the English could raise two men for their one, yet they knew their motions were too slow and dilatory to prevent any undertaking of theirs.” [10]

[9. Marin had sent sixty men in August to seize the house, which belonged to the trader Fraser. Dépêches de Duquesne. They carried off two men whom they found here. Letter of Fraser in Colonial Records of Pa., V. 659.]

[10. Journal of Washington, as printed at Williamsburg, just after his return.]

With all their civility, the French officers did their best to entice away Washington’s Indians; and it was with extreme difficulty that he could persuade them to go with him. Through marshes and swamps, forests choked with snow, and drenched with incessant rain, they toiled on for four days more, till the wooden walls of Fort Le Boeuf appeared at last, surrounded by fields studded thick with stumps, and half-encircled by the chill current of French Creek, along the banks of which lay more than two hundred canoes, ready to carry troops in the spring. Washington describes Legardeur de Saint-Pierre as “an elderly gentleman with much the air of a soldier.” The letter sent him by Dinwiddie expressed astonishment that his troops should build forts upon lands “so notoriously known to be the property of the Crown of Great Britain.” “I must desire you,” continued the letter, “to acquaint me by whose authority and instructions you have lately marched from Canada with an armed force and invaded the King of Great Britain’s territories. It becomes my duty to require your peaceable departure; and that you would forbear prosecuting a purpose so interruptive of the harmony and good understanding which His Majesty is desirous to continue and cultivate with the Most Christian King. I persuade myself you will receive and entertain Major Washington with the candor and politeness natural to your nation; and it will give me the greatest satisfaction if you return him with an answer suitable to my wishes for a very long and lasting peace between us.”

Saint-Pierre took three days to frame the answer. In it he said that he should send Dinwiddie’s letter to the Marquis Duquesne and wait his orders; and that meanwhile he should remain at his post, according to the commands of his general. “I made it my particular care,” so the letter closed, “to receive Mr. Washington with a distinction suitable to your dignity as well as his own quality and great merit.” [11] No form of courtesy had, in fact, been wanting. “He appeared to be extremely complaisant,” says Washington, “though he was exerting every artifice to set our Indians at variance with us. I saw that every stratagem was practiced to win the Half-King to their interest.” Neither gifts nor brandy were spared; and it was only by the utmost pains that Washington could prevent his red allies from staying at the fort, conquered by French blandishments.

[11. “La Distinction qui convient à votre Dignitté à sa Qualité et à son grand Mérite.” Copy of original letter sent by Dinwiddie to Governor Hamilton.]

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 5 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

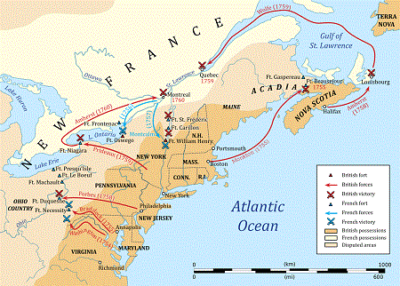

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.