The French had never reconciled themselves to the loss of Acadia, and were resolved, by diplomacy or force, to win it back again.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in Montcalm and Wolfe, Volume 7 of the French in Canada series. Continuing Chapter 4.

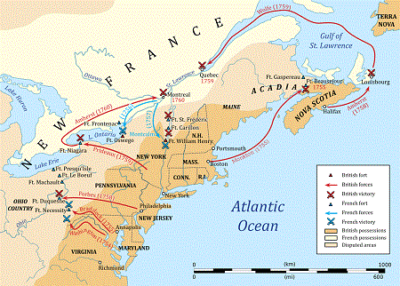

Before summer was over, the streets were laid out, and the building-lot of each settler was assigned to him; before winter closed, the whole were under shelter, the village was fenced with palisades and defended by redoubts of timber, and the battalions lately in garrison at Louisbourg manned the wooden ramparts. Succeeding years brought more emigrants, till in 1752 the population was above four thousand. Thus, was born into the world the city of Halifax. Along with the crumbling old fort and miserably disciplined garrison at Annapolis, besides six or seven small detached posts to watch the Indians and Acadians, it comprised the whole British force on the peninsula; for Canseau had been destroyed by the French.

The French had never reconciled themselves to the loss of Acadia, and were resolved, by diplomacy or force, to win it back again; but the building of Halifax showed that this was to be no easy task and filled them at the same time with alarm for the safety of Louisbourg. On one point, at least, they saw their policy clear. The Acadians, though those of them who were not above thirty-five had been born under the British flag, must be kept French at heart, and taught that they were still French subjects. In 1748 they numbered eighty-eight hundred and fifty communicants, or from twelve to thirteen thousand souls; but an emigration, of which the causes will soon appear, had reduced them in 1752 to but little more than nine thousand. [1] These were divided into six principal parishes, one of the largest being that of Annapolis. Other centres of population were Grand Pré, on the basin of Mines; Beaubassin, at the head of Chignecto Bay; Pisiquid, now Windsor; and Cobequid, now Truro. Their priests, who were missionaries controlled by the diocese of Quebec, acted also as their magistrates, ruling them for this world and the next. Bring subject to a French superior, and being, moreover, wholly French at heart, they formed in this British province a wheel within a wheel, the inner movement always opposing the outer.

[1. Description de l’Acadie, avec le Nom des Paroisses et le Nombre des Habitants, 1748. Mémoire à présenter à la Cour sur la Necessité de fixer les Limites de l’Acadie, par l’Abbé de l’Isle-Dieu, 1753 (1754?). Compare the estimates in Censuses of Canada (Ottawa, 1876.)]

Although, by the twelfth article of the treaty of Utrecht, France had solemnly declared the Acadians to be British subjects, the Government of Louis XV. intrigued continually to turn them from subjects into enemies. Before me is a mass of English documents on Acadian affairs from the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle to the catastrophe of 1755, and above a thousand pages of French official papers from the archives of Paris, memorials, reports, and secret correspondence, relating to the same matters. With the help of these and some collateral lights, it is not difficult to make a correct diagnosis of the political disease that ravaged this miserable country. Of a multitude of proofs, only a few can be given here; but these will suffice.

It was not that the Acadians had been ill-used by the English; the reverse was the case. They had been left in free exercise of their worship, as stipulated by treaty. It is true that, from time to time, there were loud complaints from French officials that religion was in danger, because certain priests had been rebuked, arrested, brought before the Council at Halifax, suspended from their functions, or required, on pain of banishment, to swear that they would do nothing against the interests of King George. Yet such action on the part of the provincial authorities seems, without a single exception, to have been the consequence of misconduct on the part of the priest, in opposing the Government and stirring his flock to disaffection. La Jonquière, the determined adversary of the English, reported to the bishop that they did not oppose the ecclesiastics in the exercise of their functions, and an order of Louis XV. admits that the Acadians have enjoyed liberty of religion. [2] In a long document addressed in 1750 to the Colonial Minister at Versailles, Roma, an officer at Louisbourg, testifies thus to the mildness of British rule, though he ascribes it to interested motives. “The fear that the Acadians have of the Indians is the controlling motive which makes them side with the French. The English, having in view the conquest of Canada, wished to give the French of that colony, in their conduct towards the Acadians, a striking example of the mildness of their government. Without raising the fortune of any of the inhabitants, they have supplied them for more than thirty-five years with the necessaries of life, often on credit and with an excess of confidence, without troubling their debtors, without pressing them, without wishing to force them to pay. They have left them an appearance of liberty so excessive that they have not intervened in their disputes or even punished their crimes. They have allowed them to refuse with insolence certain moderate rents payable in grain and lawfully due. They have passed over in silence the contemptuous refusal of the Acadians to take titles from them for the new lands which they chose to occupy.

[2. La Jonquière à l’Évêque de Québec, 14 Juin, 1750. Mémoire du Roy pour servir d’Instruction au Comte de Raymond, commandant pour Sa Majesté à l’Isle Royale [Cape Breton], 24 Avril, 1751.]

“We know very well,” pursues Roma, “the fruits of this conduct in the last war; and the English know it also. Judge then what will be the wrath and vengeance of this cruel nation.” The fruits to which Roma alludes were the hostilities, open or secret, committed by the Acadians against the English. He now ventures the prediction that the enraged conquerors will take their revenge by drafting all the young Acadians on board their ships of war, and there destroying them by slow starvation. He proved, however, a false prophet. The English Governor merely required the inhabitants to renew their oath of allegiance, without qualification or evasion.

It was twenty years since the Acadians had taken such an oath; and meanwhile a new generation had grown up. The old oath pledged them to fidelity and obedience; but they averred that Phillips, then governor of the province, had given them, at the same time, assurance that they should not be required to bear arms against either French or Indians. In fact, such service had not been demanded of them, and they would have lived in virtual neutrality, had not many of them broken their oaths and joined the French war-parties. For this reason Cornwallis thought it necessary that, in renewing the pledge, they should bind themselves to an allegiance as complete as that required of other British subjects. This spread general consternation. Deputies from the Acadian settlements appeared at Halifax, bringing a paper signed with the marks of a thousand persons. The following passage contains the pith of it. “The inhabitants in general, sir, over the whole extent of this country are resolved not to take the oath which your Excellency requires of us; but if your Excellency will grant us our old oath, with an exemption for ourselves and our heirs from taking up arms, we will accept it.” [3] The answer of Cornwallis was by no means so stern as it has been represented. [4] After the formal reception he talked in private with the deputies; and “they went home in good humor, promising great things.” [5]

[3. Public Documents of Nova Scotia, 173.]

[4. See Ibid., 174, where the answer is printed.]

[5. Cornwallis to the Board of Trade, 11 Sept. 1749.]

The refusal of the Acadians to take the required oath was not wholly spontaneous but was mainly due to influence from without. The French officials of Cape Breton and Isle St. Jean, now Prince Edward Island, exerted themselves to the utmost, chiefly through the agency of the priests, to excite the people to refuse any oath that should commit them fully to British allegiance. At the same time means were used to induce them to migrate to the neighboring islands under French rule, and efforts were also made to set on the Indians to attack the English. But the plans of the French will best appear in a dispatch sent by La Jonquière to the Colonial Minister in the autumn of 1749.

Monsieur Cornwallis issued an order on the tenth of the said month [August], to the effect that if the inhabitants will remain faithful subjects of the King of Great Britain, he will allow them priests and public exercise of their religion, with the understanding that no priest shall officiate without his permission or before taking an oath of fidelity to the King of Great Britain. Secondly, that the inhabitants shall not be exempted from defending their houses, their lands, and the Government. Thirdly, that they shall take an oath of fidelity to the King of Great Britain, on the twenty-sixth of this month, before officers sent them for that purpose.”

La Jonquière proceeds to say that on hearing these conditions the Acadians were filled with perplexity and alarm, and that he, the governor, had directed Boishébert, his chief officer on the Acadian frontier, to encourage them to leave their homes and seek asylum on French soil. He thus recounts the steps he has taken to harass the English of Halifax by means of their Indian neighbors. As peace had been declared, the operation was delicate; and when three of these Indians came to him from their missionary, Le Loutre, with letters on the subject, La Jonquière was discreetly reticent. “I did not care to give them any advice upon the matter, and confined myself to a promise that I would on no account abandon them; and I have provided for supplying them with everything, whether arms, ammunition, food, or other necessaries. It is to be desired that these savages should succeed in thwarting the designs of the English, and even their settlement at Halifax. They are bent on doing so; and if they can carry out their plans, it is certain that they will give the English great trouble, and so harass them that they will be a great obstacle in their path. These savages are to act alone; neither soldier nor French inhabitant is to join them; everything will be done of their own motion, and without showing that I had any knowledge of the matter. This is very essential; therefore, I have written to the Sieur de Boishébert to observe great prudence in his measures, and to act very secretly, in order that the English may not perceive that we are providing for the needs of the said savages.

It will be the missionaries who will manage all the negotiation, and direct the movements of the savages, who are in excellent hands, as the Reverend Father Germain and Monsieur l’Abbé Le Loutre are very capable of making the most of them and using them to the greatest advantage for our interests. They will manage their intrigue in such a way as not to appear in it.”

La Jonquière then recounts the good results which he expects from these measures: first, the English will be prevented from making any new settlements; secondly, we shall gradually get the Acadians out of their hands; and lastly, they will be so discouraged by constant Indian attacks that they will renounce their pretensions to the parts of the country belonging to the King of France. “I feel, Monseigneur,”–thus the Governor concludes his dispatch, — “all the delicacy of this negotiation; be assured that I will conduct it with such precaution that the English will not be able to say that my orders had any part in it.”

[La Jonquière au Ministre, 9 Oct. 1749.]

He kept his word, and so did the missionaries. The Indians gave great trouble on the outskirts of Halifax and murdered many harmless settlers; yet the English authorities did not at first suspect that they were hounded on by their priests, under the direction of the Governor of Canada, and with the privity of the Minister at Versailles. More than this; for, looking across the sea, we find royalty itself lending its august countenance to the machination. Among the letters read before the King in his cabinet in May, 1750, was one from Desherbiers, then commanding at Louisbourg, saying that he was advising the Acadians not to take the oath of allegiance to the King of England; another from Le Loutre, declaring that he and Father Germain were consulting together how to disgust the English with their enterprise of Halifax; and a third from the Intendant, Bigot, announcing that Le Loutre was using the Indians to harass the new settlement, and that he himself was sending them powder, lead, and merchandise, “to confirm them in their good designs.”

[Resumé des Lettres lues au Travail du Roy, Mai, 1750.]

From Montcalm and Wolfe, Chapter 4 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

A very large amount of unpublished material has been used in its preparation, consisting for the most part of documents copied from the archives and libraries of France and England, especially from the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, the Archives de la Guerre, and the Archives Nationales at Paris, and the Public Record Office and the British Museum at London. The papers copied for the present work in France alone exceed six thousand folio pages of manuscript, additional and supplementary to the “Paris Documents” procured for the State of New York under the agency of Mr. Brodhead. The copies made in England form ten volumes, besides many English documents consulted in the original manuscript. Great numbers of autograph letters, diaries, and other writings of persons engaged in the war have also been examined on this side of the Atlantic.

I owe to the kindness of the present Marquis de Montcalm the permission to copy all the letters written by his ancestor, General Montcalm, when in America, to members of his family in France. General Montcalm, from his first arrival in Canada to a few days before his death, also carried on an active correspondence with one of his chief officers, Bourlamaque, with whom he was on terms of intimacy. These autograph letters are now preserved in a private collection. I have examined them and obtained copies of the whole. They form an interesting complement to the official correspondence of the writer, and throw the most curious side-lights on the persons and events of the time.

Besides manuscripts, the printed matter in the form of books, pamphlets, contemporary newspapers, and other publications relating to the American part of the Seven Years’ War, is varied and abundant; and I believe I may safely say that nothing in it of much consequence has escaped me. The liberality of some of the older States of the Union, especially New York and Pennsylvania, in printing the voluminous records of their colonial history, has saved me a deal of tedious labor.

The whole of this published and unpublished mass of evidence has been read and collated with extreme care, and more than common pains have been taken to secure accuracy of statement. The study of books and papers, however, could not alone answer the purpose. The plan of the work was formed in early youth; and though various causes have long delayed its execution, it has always been kept in view. Meanwhile, I have visited and examined every spot where events of any importance in connection with the contest took place, and have observed with attention such scenes and persons as might help to illustrate those I meant to describe. In short, the subject has been studied as much from life and in the open air as at the library table.

BOSTON, Sept. 16, 1884.

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.