The various fortifications, public and private, were garrisoned, sometimes by the owner and his neighbors, sometimes by men in pay of the Provincial Assembly.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 24.

The various fortifications, public and private, were garrisoned, sometimes by the owner and his neighbors, sometimes by men in pay of the Provincial Assembly. As was to be expected from a legislative body undertaking warlike operations, the work of defense was but indifferently conducted. John Stoddard, the village magnate of Northampton, was charged, among the rest of his multifarious employments, with the locating and construction of forts; Captain Ephraim Williams was assigned to the general command on the western frontier, with headquarters at Fort Shirley and afterwards at Fort Massachusetts; and Major Israel Williams, of Hatfield, was made commissary.

The various fortifications, public and private, were garrisoned, sometimes by the owner and his neighbors, sometimes by men in pay of the Provincial Assembly. As was to be expected from a legislative body undertaking warlike operations, the work of defense was but indifferently conducted. John Stoddard, the village magnate of Northampton, was charged, among the rest of his multifarious employments, with the locating and construction of forts; Captain Ephraim Williams was assigned to the general command on the western frontier, with headquarters at Fort Shirley and afterwards at Fort Massachusetts; and Major Israel Williams, of Hatfield, was made commissary.

At Northfield dwelt the Rev. Benjamin Doolittle, minister, apothecary, physician, and surgeon of the village; for he had studied medicine no less than theology. His parishioners thought that his cure of bodies encroached on his cure of souls and requested him to confine his attention to his spiritual charge; to which he replied that he could not afford it, his salary as minister being seventy-five pounds in irredeemable Massachusetts paper, while his medical and surgical practice brought him full four hundred a year. He offered to comply with the wishes of his flock if they would add that amount to his salary, — which they were not prepared to do, and the minister continued his heterogeneous labors as before.

As the position of his house on the village street seems to have been regarded as strategic, the town voted to fortify it with a blockhouse and a stockade, for the benefit both of the occupant and of all the villagers. This was accordingly done, at the cost of eighteen pounds, seven shillings, and sixpence for the blockhouse, and a farther charge for the stockade; and thenceforth Mr. Doolittle could write his sermons and mix his doses in peace. To his other callings he added that of historiographer. When, after a ministry of thirty-six years, the thrifty pastor was busied one day with hammer and nails in mending the fence of his yard, he suddenly dropped dead from a stroke of heart-disease, — to the grief of all Northfield; and his papers being searched, a record was found in his handwriting of the inroads of the enemy that had happened in his time on or near the Massachusetts border. Being rightly thought worthy of publication, it was printed at Boston in a dingy pamphlet, now extremely rare, and much prized by antiquarians.

[A short Narrative of Mischief done by the French and Indian Enemy, on the Western Frontiers of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay; from the Beginning of the French War, proclaimed by the King of France, March 15th, 1743-4; and by the King of Great Britain, March 29th, 1744, to August 2nd, 1748. Drawn up by the Rev. Mr. Doolittle, of Northfield, in the County of Hampshire; and found among his Manuscripts after his Death. And at the Desire of some is now Published, with some small Additions to render it more perfect. Boston; Printed and sold by S. Kneeland, in Queen Street. MDCCL.

The facts above given concerning Mr. Doolittle are drawn from the excellent History of Northfield by Temple and Sheldon, and the introduction to the Particular History of the Five Years’ French and Indian War, by S. G. Drake.]

Appended to it are the remarks of the author on the conduct of the war. He complains that plans are changed so often that none of them take effect; that terms of enlistment are so short that the commissary can hardly serve out provisions to the men before their time is expired; that neither bread, meat, shoes, nor blankets are kept on hand for an emergency, so that the enemy escape while the soldiers are getting ready to pursue them; that the pay of a drafted man is so small that twice as much would not hire a laborer to take care of his farm in his absence; and that untried and unfit persons are commissioned as officers: in all of which strictures there is no doubt much truth.

Mr. Doolittle’s rueful narrative treats mainly of miscellaneous murders and scalpings, interesting only to the sufferers and their friends; but he also chronicles briefly a formidable inroad that still holds a place in New England history.

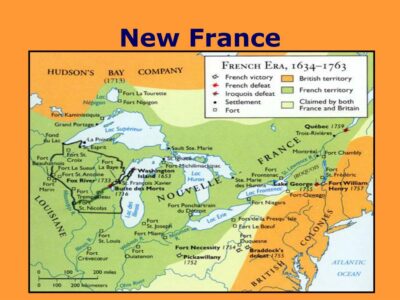

It may be remembered that Shirley had devised a plan for capturing Fort Frédéric, or Crown Point, built by the French at the narrows of Lake Champlain, and commanding ready access for war-parties to New York and New England.

The approach of D’Anville’s fleet had defeated the plan; but rumors of it had reached Canada, and excited great alarm. Large bodies of men were ordered to Lake Champlain to protect the threatened fort. The two brothers De Muy were already on the lake with a numerous party of Canadians and Indians, both Christian and heathen, and Rigaud de Vaudreuil, town-major of Three Rivers, was ordered to follow with a still larger force, repel any English attack, or, if none should be made, take the offensive and strike a blow at the English frontier. On the third of August, Rigaud[1] left Montreal with a fleet of canoes carrying what he calls his army, and on the twelfth he encamped on the east side of the lake, at the mouth of Otter Creek. There was rain, thunder, and a violent wind all night; but the storm ceased at daybreak, and, embarking again, they soon saw the octagonal stone tower of Fort Frédéric.

[1: French writers always call him Rigaud, to distinguish him from his brother, Pierre Rigaud de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal, afterwards governor of Canada, who is usually mentioned as Vaudreuil.]

The party set up their tents and wigwams near the fort, and on the morning of the sixteenth the elder De Muy arrived with a reinforcement of sixty Frenchmen and a band of Indians. They had just returned from an incursion towards Albany, and reported that all was quiet in those parts, and that Fort Frédéric was in no danger. Now, to their great satisfaction, Rigaud and his

band saw themselves free to take the offensive. The question was, where to strike. The Indians held council after council, made speech after speech, and agreed on nothing. Rigaud gave them a wampum-belt, and told them that he meant to attack Corlaer, — that is, Schenectady; at which they seemed well pleased, and sang war-songs all night. In the morning they changed their minds and begged him to call the whole army to a council for debating the question. It appeared that some of them, especially the Iroquois converts of Caughnawaga, disapproved of attacking Schenectady, because some of their Mohawk relatives were always making visits there, and might be inadvertently killed by the wild western Indians of Rigaud’s party. Now all was doubt again, for as Indians are unstable as water, it was no easy task to hold them to any plan of action.

The Abenakis proposed a solution of the difficulty. They knew the New England border well, for many of them had lived upon it before the war, on terms of friendly intercourse with the settlers. They now drew upon the floor of the council-room a rough map of the country, on which was seen a certain river, and on its upper waters a fort which they recommended as a proper object of attack. The river was that eastern tributary of the Hudson which the French called the Kaskékouké, the Dutch the Schaticook, and the English the Hoosac. The fort was Fort Massachusetts, the most westerly of the three posts lately built to guard the frontier. “My father,” said the Abenaki spokesman to Rigaud, “it will be easy to take this fort, and make great havoc on the lands of the English. Deign to listen to your children and follow our advice.”[2] One Cadenaret, an Abenaki chief, had been killed near Fort Massachusetts in the last spring, and his tribesmen were keen to revenge him. Seeing his Indians pleased with the proposal to march for the Hoosac, Rigaud gladly accepted it; on which whoops, yelps, and war-songs filled the air. Hardly, however, was the party on its way when the Indians changed their minds again and wanted to attack Saratoga; but Rigaud told them that they had made their choice and must abide by it, to which they assented, and gave him no farther trouble.

[2: Journal de la Campagne de Rigaud de Vaudreuil en 1746 … présenté à Monseigneur le Comte de Maurepas, Ministre et Secrétaire d’État (written by Rigaud).]

On the twentieth of August they all embarked and paddled southward, passed the lonely promontory where Fort Ticonderoga was afterwards built, and held their course till the lake dwindled to a mere canal creeping through the weedy marsh then called the Drowned Lands. Here, nine summers later, passed the flotilla of Baron Dieskau, bound to defeat and ruin by the shores of Lake George. Rigaud stopped at a place known as East Bay, at the mouth of a stream that joins Wood Creek, just north of the present town of Whitehall. Here he left the younger De Muy, with thirty men, to guard the canoes. The rest of the party, guided by a brother of the slain Cadenaret, filed southward on foot along the base of Skene Mountain, that overlooks Whitehall. They counted about seven hundred men, of whom five hundred were French, and a little above two hundred were Indians.[3] Some other French reports put the whole number at eleven hundred, or even twelve hundred,[4] while several English accounts make it eight hundred or nine hundred. The Frenchmen of the party included both regulars and Canadians, with six regular officers and ten cadets, eighteen militia officers, two chaplains, — one for the whites and one for the Indians, — and a surgeon.[5]

[3: “Le 19, ayant fait passer l’armée en Revue qui se trouva de 700 hommes, scavoir 500 françois environ et 200 quelques sauvages.” — Journal de Rigaud.]

[4: See N. Y. Col. Docs., x. 103, 132.]

[5: Ibid., x. 35.]

After a march of four days, they encamped on the twenty-sixth by a stream which ran into the Hudson, and was no doubt the Batten Kill, known to the French as la rivière de Saratogue. Being nearly opposite Saratoga, where there was then a garrison, they changed their course, on the twenty-seventh, from south to southeast, the better to avoid scouting-parties, which might discover their trail and defeat their plan of surprise. Early on the next day they reached the Hoosac, far above its mouth; and now their march was easier, “for,” says Rigaud, “we got out of the woods and followed a large road that led up the river.” In fact, there seem to have been two roads, one on each side of the Hoosac; for the French were formed into two brigades, one of which, under the Sieur de la Valterie, filed along the right bank of the stream, and the other, under the Sieur de Sabrevois, along the left; while the Indians marched on the front, flanks, and rear. They passed deserted houses and farms belonging to Dutch settlers from the Hudson; for the Hoosac, in this part of its course, was in the province of New York.[6] They did not stop to burn barns and houses, but they killed poultry, hogs, a cow, and a horse, to supply themselves with meat. Before night they had passed the New York line, and they made their camp in or near the valley where Williamstown and Williams College now stand. Here they were joined by the Sieurs Beaubassin and La Force, who had gone forward, with eight Indians, to reconnoiter. Beaubassin had watched Fort Massachusetts from a distance and had seen a man go up into the watch-tower but could discover no other sign of alarm. Apparently, the fugitive Dutch farmers had not taken pains to warn the English garrison of the coming danger, for there was a coolness between the neighbors.

[6: These Dutch settlements on the Hoosac were made under what was called the “Hoosac Patent,” granted by Governor Dongan of New York in 1688. The settlements were not begun till nearly forty years after the grant was made. For evidence on this point I am indebted to Professor A. L. Perry, of Williams College.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 24 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.