Then it was a rough clearing, encumbered with the stumps and refuse of the primeval forest, whose living hosts stood grimly around it, and spread, untouched by the axe, up the sides of the neighboring Saddleback Mountain.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 24.

Before breaking up camp in the morning, Rigaud called the Indian chiefs together and said to them: “My children, the time is near when we must get other meat than fresh pork, and we will all eat it together.” “Meat,” in Indian parlance, meant prisoners; and as these were valuable by reason of the ransoms paid for them, and as the Indians had suspected that the French meant to keep them all, they were well pleased with this figurative assurance of Rigaud that they should have their share.

Before breaking up camp in the morning, Rigaud called the Indian chiefs together and said to them: “My children, the time is near when we must get other meat than fresh pork, and we will all eat it together.” “Meat,” in Indian parlance, meant prisoners; and as these were valuable by reason of the ransoms paid for them, and as the Indians had suspected that the French meant to keep them all, they were well pleased with this figurative assurance of Rigaud that they should have their share.

[“Mes enfans, leur dis-je, le temps approche où il faut faire d’autre viande que le porc frais; au reste, nous la mangerons tous ensemble; ce mot les flatta dans la crainte qu’ils avoient qu’après la prise du fort nous ne nous réservâmes tous les prisonniers.” — Journal de Rigaud.]

The chaplain said mass, and the party marched in a brisk rain up the Williamstown valley, till after advancing about ten miles they encamped again. Fort Massachusetts was only three or four miles distant. Rigaud held a talk with the Abenaki chiefs who had acted as guides, and it was agreed that the party should stop in the woods near the fort, make scaling-ladders, battering-rams to burst the gates, and other things needful for a grand assault, to take place before daylight; but their plan came to nought through the impetuosity of the young Indians and Canadians, who were so excited at the first glimpse of the watch-tower of the fort that they dashed forward, as Rigaud says, “like lions.” Hence one might fairly expect to see the fort assaulted at once; but by the maxims of forest war this would have been reprehensible rashness, and nothing of the kind was attempted. The assailants spread to right and left, squatted behind stumps, and opened a distant and harmless fire, accompanied with unearthly yells and howlings.

Fort Massachusetts was a wooden enclosure formed, like the fort at Number Four, of beams laid one upon another, and interlocked at the angles. This wooden wall seems to have rested, not immediately upon the ground, but upon a foundation of stone, designated by Mr. Norton, the chaplain, as the “underpinning,” — a name usually given in New England to foundations of the kind. At the northwest corner was a blockhouse,[1] crowned with the watch-tower, the sight of which had prematurely kindled the martial fire of the Canadians and Indians. This wooden structure, at the apex of the blockhouse, served as a lookout, and also supplied means of throwing water to extinguish fire-arrows shot upon the roof. There were other buildings in the enclosure, especially a large log-house on the south side, which seems to have overlooked the outer wall, and was no doubt loop-holed for musketry. On the east side there was a well, furnished probably with one of those long well-sweeps universal in primitive New England. The garrison, when complete, consisted of fifty-one men under Captain Ephraim Williams, who has left his name to Williamstown and Williams College, of the latter of which he was the founder. He was born at Newton, near Boston; was a man vigorous in body and mind; better acquainted with the world than most of his countrymen, having followed the seas in his youth, and visited England, Spain, and Holland; frank and agreeable in manners, well fitted for such a command, and respected and loved by his men.[2] When the proposed invasion of Canada was preparing, he and some of his men went to take part in it, and had not yet returned. The fort was left in charge of a sergeant, John Hawks, of Deerfield, with men too few for the extent of the works, and a supply of ammunition nearly exhausted. Canada being then put on the defensive, the frontier forts were thought safe for a time. On the Saturday before Rigaud’s arrival, Hawks had sent Thomas Williams, the surgeon, brother of the absent captain, to Deerfield, with a detachment of fourteen men, to get a supply of powder and lead. This detachment reduced the entire force, including Hawks himself and Norton, the chaplain, to twenty-two men, half of whom were disabled with dysentery, from which few of the rest were wholly free.[3] There were also in the fort three women and five children.[4]

[1: The term “blockhouse” was loosely used, and was even sometimes applied to an entire fort when constructed of hewn logs, and not of palisades. The true blockhouse of the New England frontier was a solid wooden structure about twenty feet high, with a projecting upper story and loopholes above and below.]

[2: See the notice of Williams in Mass. Hist. Coll., viii. 47. He was killed in the bloody skirmish that preceded the Battle of Lake George in 1755. “Montcalm and Wolfe,” chap. ix.]

[3: “Lord’s day and Monday … the sickness was very distressing…. Eleven of our men were sick, and scarcely one of us in perfect health; almost every man was troubled with the griping and flux.” — Norton, The Redeemed Captive.]

[4: Rigaud erroneously makes the garrison a little larger. “La garnison se trouve de 24 hommes, entre lesquels il y avoit un ministre, 3 femmes, et 5 enfans.” The names and residence of all the men in the fort when the attack began are preserved. Hawks made his report to the provincial government under the title “An Account of the Company in his Majesty’s Service under the command of Serg^t. John Hawks … at Fort Massachusetts, August 20 [31, new style], 1746.” The roll is attested on oath “Before William Williams, Just. Pacis.” The number of men is 22, including Hawks and Norton. Each man brought his own gun. I am indebted to the kindness of Professor A. L. Perry for a copy of Hawks’s report, which is addressed to “the Honble. Spencer Phipps, Esq., Lieut. Gov^r. and Commander in Chief [and] the Hon^{ble}. his Majesty’s Council and House of Representatives in General Court assembled.”]

The site of Fort Massachusetts is now a meadow by the banks of the Hoosac. Then it was a rough clearing, encumbered with the stumps and refuse of the primeval forest, whose living hosts stood grimly around it, and spread, untouched by the axe, up the sides of the neighboring Saddleback Mountain. The position of the fort was bad, being commanded by high ground, from which, as the chaplain tells us, “the enemy could shoot over the north side into the middle of the parade,” — for which serious defect, John Stoddard, of Northampton, legist, capitalist, colonel of militia, and “Superintendent of Defense,” was probably answerable. These frontier forts were, however, often placed on low ground with a view to an abundant supply of water, fire being the most dreaded enemy in Indian warfare.

[When I visited the place as a college student, no trace of the fort was to be seen except a hollow, which may have been the remains of a cellar, and a thriving growth of horse-radish, — a relic of the garrison garden. My friend, Dr. D. D. Slade, has given an interesting account of the spot in the Magazine of American History for October, 1888.]

Sergeant Hawks, the provisional commander, was, according to tradition, a tall man with sunburnt features, erect, spare, very sinewy and strong, and of a bold and resolute temper. He had need to be so, for counting every man in the fort, lay and clerical, sick and well, he was beset by more than thirty times his own number; or, counting only his effective men, by more than sixty times, — and this at the lowest report of the attacking force. As there was nothing but a log fence between him and his enemy, it was clear that they could hew or burn a way through it or climb over it with no surprising effort of valor. Rigaud, as we have seen, had planned a general assault under cover of night, but had been thwarted by the precipitancy of the young Indians and Canadians. These now showed no inclination to depart from the cautious maxims of forest warfare. They made a terrific noise, but when they came within gunshot of the fort, it was by darting from stump to stump with a quick zigzag movement that made them more difficult to hit than birds on the wing. The best moment for a shot was when they reached a stump and stopped for an instant to duck and hide behind it. By seizing this fleeting opportunity, Hawks himself put a bullet into the breast of an Abenaki chief from St. Francis, — “which ended his days,” says the chaplain. In view of the nimbleness of the assailants, a charge of buckshot was found more to the purpose than a bullet. Besides the slain Abenaki, Rigaud reports sixteen Indians and Frenchman wounded,[5] — which, under the circumstances, was good execution for ten farmers and a minister; for Chaplain Norton loaded and fired with the rest. Rigaud himself was one of the wounded, having been hit in the arm and sent to the rear, as he stood giving orders on the rocky hill about forty rods from the fort. Probably it was a chance shot, since, though rifles were invented long before, they were not yet in general use, and the yeoman garrison were armed with nothing but their own smooth-bore hunting-pieces, not to be trusted at long range. The supply of ammunition had sunk so low that Hawks was forced to give the discouraging order not to fire except when necessary to keep the enemy in check, or when the chance of hitting him should be unusually good. Such of the sick men as were strong enough aided the defense by casting bullets and buckshot.

[5: “L’Ennemi me tua un abenakis et me blessa 16 hommes, tant Iroquois qu’Abenaquis, nipissings et françois.” — Journal de Rigaud.]

The outrageous noise lasted till towards nine in the evening, when the assailants greeted the fort with a general war-whoop and repeated it three or four times; then a line of sentinels was placed around it to prevent messengers from carrying the alarm to Albany or Deerfield. The evening was dark and cloudy. The lights of a camp could be seen by the river towards the southeast, and those of another near the swamp towards the west. There was a sound of axes, as if the enemy were making scaling-ladders for a night assault; but it was found that they were cutting fagots to burn the wall. Hawks ordered every tub and bucket to be filled with water, in preparation for the crisis. Two men, John Aldrich and Jonathan Bridgman, had been wounded, thus farther reducing the strength of the defenders. The chaplain says:

Of those that were in health, some were ordered to keep the watch, and some lay down and endeavored to get some rest, lying down in our clothes with our arms by us…. We got little or no rest; the enemy frequently raised us by their hideous outcries, as though they were about to attack us. The latter part of the night I kept the watch.”

Rigaud spent the night in preparing for a decisive attack, “being resolved to open trenches two hours before sunrise, and push them to the foot of the palisade, so as to place fagots against it, set them on fire, and deliver the fort a prey to the fury of the flames.”[6] It began to rain, and he determined to wait till morning. That the commander of seven hundred French and Indians should resort to such elaborate devices to subdue a sergeant, seven militiamen, and a minister, — for this was now the effective strength of the besieged, — was no small compliment to the spirit of the defense.

[6: “Je passay la nuit à conduire l’ouvrage auquel j’avois destiné le jour précédent, résolu à faire ouvrir la tranchée deux heures avant le lever du soleil, et de la pousser jusqu’au pied de la palissade, pour y placer les fascines, y appliquer l’artifice, et livrer le fort en proye à la fureur du feu.” — Journal de Rigaud. He mistakes in calling the log wall of the fort a palisade.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 24 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

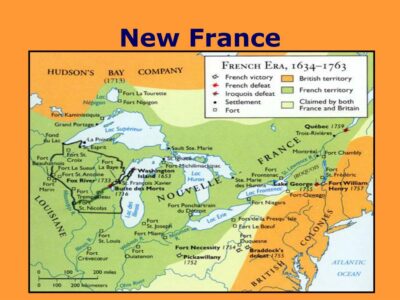

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.