In due time the prisoners reached Montreal, whence they were sent to Quebec; and in the course of the next year those who remained alive were exchanged and returned to New England.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 24.

The firing was renewed in the morning, but there was no attempt to open trenches by daylight. Two men were sent up into the watch-tower, and about eleven o’clock one of them, Thomas Knowlton, was shot through the head. The number of effectives was thus reduced to eight, including the chaplain. Up to this time the French and English witnesses are in tolerable accord; but now there is conflict of evidence. Rigaud says that when he was about to carry his plan of attack into execution, he saw a white flag hung out, and sent the elder De Muy, with Montigny and D’Auteuil, to hear what the English commandant — whose humble rank he nowhere mentions — had to say. On the other hand, Norton, the chaplain, says that about noon the French “desired to parley,” and that “we agreed to it.” He says farther that the sergeant, with himself and one or two others, met Rigaud outside the gate, and that the French commander promised “good quarter” to the besieged if they would surrender, with the alternative of an assault if they would not. This account is sustained by Hawks, who says that at twelve o’clock an Indian came forward with a flag of truce, and that he, Hawks, with two or three others, went to meet Rigaud, who then offered honorable terms of capitulation.[1] The sergeant promised an answer within two hours; and going back to the fort with his companions, examined their means of defense. He found that they had left but three or four pounds of gunpowder, and about as much lead. Hawks called a council of his effective men. Norton prayed for divine aid and guidance, and then they fell to considering the situation. “Had we all been in health or had there been only those eight of us that were in health, I believe every man would willingly have stood it out to the last. For my part, I should,” writes the manful chaplain. But besides the sick and wounded, there were three women and five children, who, if the fort were taken by assault, would no doubt be butchered by the Indians, but who might be saved by a capitulation. Hawks therefore resolved to make the best terms he could. He had defended his post against prodigious odds for twenty-eight hours. Rigaud promised that all in the fort should be treated with humanity as prisoners of war and exchanged at the first opportunity. He also promised that none of them should be given to the Indians, though he had lately assured his savage allies that they should have their share of the prisoners.

The firing was renewed in the morning, but there was no attempt to open trenches by daylight. Two men were sent up into the watch-tower, and about eleven o’clock one of them, Thomas Knowlton, was shot through the head. The number of effectives was thus reduced to eight, including the chaplain. Up to this time the French and English witnesses are in tolerable accord; but now there is conflict of evidence. Rigaud says that when he was about to carry his plan of attack into execution, he saw a white flag hung out, and sent the elder De Muy, with Montigny and D’Auteuil, to hear what the English commandant — whose humble rank he nowhere mentions — had to say. On the other hand, Norton, the chaplain, says that about noon the French “desired to parley,” and that “we agreed to it.” He says farther that the sergeant, with himself and one or two others, met Rigaud outside the gate, and that the French commander promised “good quarter” to the besieged if they would surrender, with the alternative of an assault if they would not. This account is sustained by Hawks, who says that at twelve o’clock an Indian came forward with a flag of truce, and that he, Hawks, with two or three others, went to meet Rigaud, who then offered honorable terms of capitulation.[1] The sergeant promised an answer within two hours; and going back to the fort with his companions, examined their means of defense. He found that they had left but three or four pounds of gunpowder, and about as much lead. Hawks called a council of his effective men. Norton prayed for divine aid and guidance, and then they fell to considering the situation. “Had we all been in health or had there been only those eight of us that were in health, I believe every man would willingly have stood it out to the last. For my part, I should,” writes the manful chaplain. But besides the sick and wounded, there were three women and five children, who, if the fort were taken by assault, would no doubt be butchered by the Indians, but who might be saved by a capitulation. Hawks therefore resolved to make the best terms he could. He had defended his post against prodigious odds for twenty-eight hours. Rigaud promised that all in the fort should be treated with humanity as prisoners of war and exchanged at the first opportunity. He also promised that none of them should be given to the Indians, though he had lately assured his savage allies that they should have their share of the prisoners.

[1: Journal of Sergeant Hawks, cited by William L. Stone, Life and Times of Sir William Johnson, i. 227. What seems conclusive is that the French permitted Norton to nail to a post of the fort a short account of its capture, in which it is plainly stated that the first advances were made by Rigaud.]

At three o’clock the principal French officers were admitted into the fort, and the French flag was raised over it. The Indians and Canadians were excluded; on which some of the Indians pulled out several of the stones that formed the foundation of the wall, crawled through, opened the gate, and let in the whole crew. They raised a yell when they saw the blood of Thomas Knowlton trickling from the watch-tower where he had been shot, then rushed up to where the corpse lay, brought it down, scalped it, and cut off the head and arms. The fort was then plundered, set on fire, and burned to the ground.

The prisoners were led to the French camp; and here the chaplain was presently accosted by one Doty, Rigaud’s interpreter, who begged him to persuade some of the prisoners to go with the Indians. Norton replied that it had been agreed that they should all remain with the French; and that to give up any of them to the Indians would be a breach of the capitulation. Doty then appealed to the men themselves, who all insisted on being left with the French, according to the terms stipulated. Some of them, however, were given to the Indians, who, after Rigaud’s promise to them, could have been pacified in no other way. His fault was in making a stipulation that he could not keep. Hawks and Norton, with all the women and children, remained in the French camp.

Hearing that men were expected from Deerfield to take the places of the sick, Rigaud sent sixty Indians to cut them off. They lay in wait for the English reinforcement, which consisted of nineteen men, gave them a close fire, shot down fifteen of them, and captured the rest.[2] This or another party of Rigaud’s Indians pushed as far as Deerfield and tried to waylay the farmers as they went to their work on a Monday morning. The Indians hid in a growth of alder-bushes along the edge of a meadow where men were making hay, accompanied by some children. One Ebenezer Hawks, shooting partridges, came so near the ambushed warriors that they could not resist the temptation of killing and scalping him. This alarmed the haymakers and the children, who ran for their lives towards a mill on a brook that entered Deerfield River, fiercely pursued by about fifty Indians, who caught and scalped a boy named Amsden. Three men, Allen, Sadler, and Gillet, got under the bank of the river and fired on the pursuers. Allen and Gillet were soon killed, but Sadler escaped unhurt to an island. Three children of Allen — Eunice, Samuel, and Caleb — were also chased by the Indians, who knocked down Eunice with a tomahawk, but were in too much haste to stop and scalp her, and she lived to a good old age. Her brother Samuel was caught and dragged off, but Caleb ran into a field of tall maize, and escaped.

[2: One French account says that the Indians failed to meet the English party. N. Y. Col. Docs. x. 35.]

The firing was heard in the village, and a few armed men, under Lieutenant Clesson, hastened to the rescue; but when they reached the spot the Indians were gone, carrying the boy Samuel Allen with them and leaving two of their own number dead. Clesson, with such men as he had, followed their trail up Deerfield River, but could not overtake the light-footed savages.

Meanwhile, the prisoners at Fort Massachusetts spent the first night, well guarded, in the French and Indian camps. In the morning, Norton, accompanied by a Frenchman and several Indians, was permitted to nail to one of the charred posts of the fort a note to tell what had happened to him and his companions.[3] The victors then marched back as they had come, along the Hoosac road. They moved slowly, encumbered as they were by the sick and wounded. Rigaud gave the Indians presents, to induce them to treat their prisoners with humanity. Norton was in charge of De Muy, and after walking four miles sat down with him to rest in Williamstown valley. There was a yell from the Indians in the rear. “I trembled,” writes Norton, “thinking they had murdered some of our people, but was filled with admiration when I saw all our prisoners come up with us, and John Aldrich carried on the back of his Indian master.” Aldrich had been shot in the foot and could not walk. “We set out again and had gone but a little way before we came up with Josiah Reed.” Reed was extremely ill and could go no farther. Norton thought that the Indians would kill him, instead of which one of them carried him on his back. They were said to have killed him soon after, but there is good reason to think that he died of disease. “I saw John Perry’s wife,” pursues the chaplain; “she complained that she was almost ready to give out.” The Indians threatened her, but Hawks spoke in her behalf to Rigaud, who remonstrated with them, and they afterwards treated her well. The wife of another soldier, John Smead, was near her time, and had lingered behind. The French showed her great kindness. “Some of them made a seat for her to sit upon, and brought her to the camp, where, about ten o’clock, she was graciously delivered of a daughter, and was remarkably well…. Friday: this morning I baptized John Smead’s child. He called its name Captivity.” The French made a litter of poles, spread over it a deerskin and a bearskin, on which they placed the mother and child, and so carried them forward. Three days after, there was a heavy rain, and the mother was completely drenched, but suffered no harm, though “Miriam, the wife of Moses Scott, hereby catched a grievous cold.” John Perry was relieved of his pack, so that he might help his wife and carry her when her strength failed. Several horses were found at the farms along the way, and the sick Benjamin Simons and the wounded John Aldrich were allowed to use two of them. Rarely, indeed, in these dismal border-raids were prisoners treated so humanely; and the credit seems chiefly due to the efforts of Rigaud and his officers. The hardships of the march were shared by the victors, some of whom were sorely wounded; and four Indians died within a few days.

[3: The note was as follows: “August 20 [31, new style], 1746. These are to inform you that yesterday, about 9 of the clock, we were besieged by, as they say, seven hundred French and Indians. They have wounded two men and killed one Knowlton. The General de Vaudreuil desired capitulations, and we were so distressed that we complied with his terms. We are the French’s prisoners, and have it under the general’s hand that every man, woman, and child shall be exchanged for French prisoners.”]

“I divided my army between the two sides of the Kaskékouké” (Hoosac), says Rigaud, “and ordered them to do what I had not permitted to be done before we reached Fort Massachusetts. Every house was set on fire, and numbers of domestic animals of all sorts were killed. French and Indians vied with each other in pillage, and I made them enter the [valleys of all the] little streams that flow into the Kaskékouké and lay waste everything there…. Wherever we went we made the same havoc, laid waste both sides of the river, through twelve leagues of fertile country, burned houses, barns, stables, and even a meeting-house, — in all, above two hundred establishments, — killed all the cattle, and ruined all the crops. Such, Monseigneur, was the damage I did our enemies during the eight or nine days I was in their country.”[4] As the Dutch settlers had escaped, there was no resistance.

[4: Journal de Rigaud.]

The French and their allies left the Hoosac at the point where they had reached it, and retraced their steps northward through the forest, where there was an old Indian trail. Recrossing the Batten Kill, or “River of Saratoga,” and some branches of Wood Creek, they reached the place where they had left their canoes and found them safe. Rigaud says: “I gave leave to the Indians, at their request, to continue their fighting and ravaging, in small parties, towards Albany, Schenectady, Deerfield, Saratoga, or wherever they pleased, and I even gave them a few officers and cadets to lead them.” These small ventures were more or less successful, and produced, in due time, a good return of scalps.

The main body, now afloat again, sailed and paddled northward till they reached Crown Point. Rigaud rejoiced at finding a haven of refuge, for his wounded arm was greatly inflamed: “and it was time I should reach a place of repose.” He and his men encamped by the fort and remained there for some time. An epidemic, apparently like that at Fort Massachusetts, had broken out among them, and great numbers were seriously ill.

Norton was lodged in a French house on the east side of the lake, at what is now called Chimney Point; and one day his guardian, De Muy, either thinking to impress him with the strength of the place, or with an amusing confidence in the minister’s incapacity for making inconvenient military observations, invited him to visit the fort. He accepted the invitation, crossed over with the courteous officer, and reports the ramparts to have been twenty feet thick, about twenty feet high, and mounted with above twenty cannon. The octagonal tower which overlooked the ramparts and answered in some sort to the donjon of a feudal castle, was a bomb-proof structure in vaulted masonry, of the slaty black limestone of the neighborhood, three stories in height, and armed with nine or ten cannon, besides a great number of patereroes, — a kind of pivot-gun much like a swivel.

[Kalm also describes the fort and its tower. Little trace of either now remains. Amherst demolished them in 1759, when he built the larger fort, of which the ruins still stand on the higher ground behind the site of its predecessor.]

In due time the prisoners reached Montreal, whence they were sent to Quebec; and in the course of the next year those who remained alive were exchanged and returned to New England.[5] Mrs. Smead and her infant daughter “Captivity” died in Canada, and, by a singular fatality, her husband had scarcely returned home when he was waylaid and killed by Indians. Fort Massachusetts was soon rebuilt by the province and held its own thenceforth till the war was over. Sergeant Hawks became a lieutenant-colonel and took a creditable part in the last French war.

[6: Of the twenty-two men in the fort when attacked, one, Knowlton, was killed by a bullet; one, Reed, died just after the surrender; ten died in Canada, and ten returned home. Report of Sergeant Hawks.]

For two years after the incursion of Rigaud the New England borders were scourged with partisan warfare, bloody, monotonous, and futile, with no event that needs recording, and no result beyond a momentary check to the progress of settlement. At length, in July, 1748, news came that the chief contending powers in Europe had come to terms of agreement, and in the next October the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle was signed. Both nations were tired of the weary and barren conflict, with its enormous cost and its vast entail of debt. It was agreed that conquests should be mutually restored. The chief conquest of England was Louisbourg, with the island of Cape Breton, — won for her by the farmers and fishermen of New England. When the preliminaries of peace were under discussion, Louis XV. had demanded the restitution of the lost fortress; and George II. is said to have replied that it was not his to give, having been captured by the people of Boston.[7] But his sense of justice was forced to yield to diplomatic necessity, for Louisbourg was the indispensable price of peace. To the indignation of the northern provinces, it was restored to its former owners. “The British ministers,” says Smollett, “gave up the important island of Cape Breton in exchange for a petty factory in the East Indies” (Madras), and the King deigned to send two English noblemen to the French court as security for the bargain.

[7: N. Y. Col Docs., x. 147.]

Peace returned to the tormented borders; the settlements advanced again, and the colonists found a short breathing space against the great conclusive struggle of the Seven Years’ War.

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 24 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

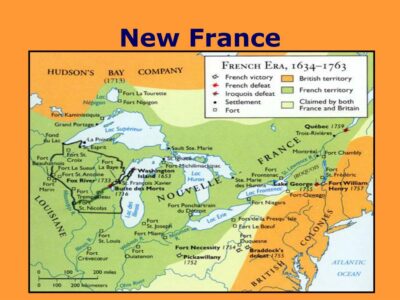

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.