This was the farthest outpost of the colony, and the only defense of Albany in the direction of Canada.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 23.

He urged upon them the necessity of building forts on the two carrying-places between the Hudson and Lakes George and Champlain, thus blocking the path of war-parties from Canada. They would do nothing, insisting that the neighboring colonies, to whom the forts would also be useful, ought to help in building them; and when it was found that these colonies were ready to do their part, the Assembly still refused. Passionate opposition to the royal governor seemed to blind them to the interests of the province. Nor was the fault all on their side; for the governor, though he generally showed more self-control and moderation than could have been expected, sometimes lost temper and betrayed scorn for his opponents, many of whom were but the instruments of leaders urged by personal animosities and small but intense ambitions. They accused him of treating them with contempt, and of embezzling public money; while he retorted by charging them with encroaching on the royal prerogative and treating the representative of the King with indecency. Under such conditions an efficient conduct of the war was out of the question.

He urged upon them the necessity of building forts on the two carrying-places between the Hudson and Lakes George and Champlain, thus blocking the path of war-parties from Canada. They would do nothing, insisting that the neighboring colonies, to whom the forts would also be useful, ought to help in building them; and when it was found that these colonies were ready to do their part, the Assembly still refused. Passionate opposition to the royal governor seemed to blind them to the interests of the province. Nor was the fault all on their side; for the governor, though he generally showed more self-control and moderation than could have been expected, sometimes lost temper and betrayed scorn for his opponents, many of whom were but the instruments of leaders urged by personal animosities and small but intense ambitions. They accused him of treating them with contempt, and of embezzling public money; while he retorted by charging them with encroaching on the royal prerogative and treating the representative of the King with indecency. Under such conditions an efficient conduct of the war was out of the question.

Once, when the frontier was seriously threatened, Clinton, as commander-in-chief, called out the militia to defend it; but they refused to obey, on the ground that no Act of the Assembly required them to do so.

[Clinton to the Lords of Trade, 10 November, 1747.]

Clinton sent home bitter complaints to Newcastle and the Lords of Trade.

They [the Assembly] are selfish, jealous of the power of the Crown, and of such levelling principles that they are constantly attacking its prerogative…. I find that neither dissolutions nor fair means can produce from them such Effects as will tend to a publick good or their own preservation. They will neither act for themselves nor assist their neighbors…. Few but hirelings have a seat in the Assembly, who protract time for the sake of their wages, at a great expence to the Province, without contributing anything material for its welfare, credit, or safety.”

And he declares that unless Parliament takes them in hand he can do nothing for the service of the King or the good of the province,[1] for they want to usurp the whole administration, both civil and military.[2]

[1: Ibid., 30 November, 1745.]

[2: Remarks on the Representation of the Assembly of New York, May, 1747, in N. Y. Col. Docs., vi. 365. On the disputes of the governor and Assembly see also Smith, History of New York, ii. (1830), and Stone, Life and Times of Sir William Johnson, i. N. Y. Colonial Documents, vi., contains many papers on the subject, chiefly on the governor’s side.]

At Saratoga there was a small settlement of Dutch farmers, with a stockade fort for their protection. This was the farthest outpost of the colony, and the only defense of Albany in the direction of Canada. It was occupied by a sergeant, a corporal, and ten soldiers, who testified before a court of inquiry that it was in such condition that in rainy weather neither they nor their ammunition could be kept dry. As neither the Assembly nor the merchants of Albany would make it tenable, the garrison was withdrawn before winter by order of the governor.

[Examinations at a Court of Inquiry at Albany, 11 December, 1745, in N. Y. Col. Docs., vi. 374.]

Scarcely was this done when five hundred French and Indians, under the partisan Marin, surprised the settlement in the night of the twenty-eighth of November, burned fort, houses, mills, and stables, killed thirty persons, and carried off about a hundred prisoners.[3] Albany was left uncovered, and the Assembly voted £150 in provincial currency to rebuild the ruined fort. A feeble palisade work was accordingly set up, but it was neglected like its predecessor. Colonel Peter Schuyler was stationed there with his regiment in 1747 but was forced to abandon his post for want of supplies. Clinton then directed Colonel Roberts, commanding at Albany, to examine the fort, and if he found it indefensible, to burn it, — which he did, much to the astonishment of a French war-party, who visited the place soon after, and found nothing but ashes.[4]

[3: The best account of this affair is in the journal of a French officer in Schuyler, Colonial New York, ii. 115. The dates, being in new style, differ by eleven days from those of the English accounts. The Dutch hamlet of Saratoga, surprised by Marin, was near the mouth of the Fish Kill, on the west side of the Hudson. There was also a small fort on the east side, a little below the mouth of the Batten Kill.]

[4: Schuyler, Colonial New York, ii. 121.]

The burning of Saratoga, first by the French and then by its own masters, made a deep impression on the Five Nations, and a few years later they taunted their white neighbors with these shortcomings in no measured terms. “You burned your own fort at Seraghtoga and ran away from it, which was a shame and a scandal to you.”[5] Uninitiated as they were in party politics and faction quarrels, they could see nothing in this and other military lapses but proof of a want of martial spirit, if not of cowardice. Hence the difficulty of gaining their active alliance against the French was redoubled. Fortunately for the province, the adverse influence was in some measure counteracted by the character and conduct of one man. Up to this time the French had far surpassed the rival nation in the possession of men ready and able to deal with the Indians and mold them to their will. Eminent among such was Joncaire, French emissary among the Senecas in western New York, who, with admirable skill, held back that powerful member of the Iroquois league from siding with the English. But now, among the Mohawks of eastern New York, Joncaire found his match in the person of William Johnson, a vigorous and intelligent young Irishman, nephew of Admiral Warren, and his agent in the

management of his estates on the Mohawk. Johnson soon became intimate with his Indian neighbors, spoke their language, joined in their games and dances, sometimes borrowed their dress and their paint, and whooped, yelped, and stamped like one of themselves. A white man thus playing the Indian usually gains nothing in the esteem of those he imitates; but, as before in the case of the redoubtable Count Frontenac, Johnson’s adoption of their ways increased their liking for him and did not diminish their respect. The Mohawks adopted him into their tribe and made him a warchief. Clinton saw his value; and as the Albany commissioners hitherto charged with Indian affairs had proved wholly inefficient, he transferred their functions to Johnson; whence arose more heartburnings. The favor of the governor cost the new functionary the support of the Assembly, who refused the indispensable presents to the Indians, and thus vastly increased the difficulty of his task. Yet the Five Nations promised to take up the hatchet against the French, and their orator said, in a conference at Albany, “Should any French priests now dare to come among us, we know no use for them but to roast them.”[6] Johnson’s present difficulties, however, sprang more from Dutch and English traders than from French priests, and he begs that an Act may be passed against the selling of liquor to the Indians, “as it is impossible to do anything with them while there is such a plenty to be had all round the neighborhood, being forever drunk.” And he complains especially of one Clement, who sells liquor within twenty yards of Johnson’s house, and immediately gets from the Indians all the bounty money they receive for scalps, “which leaves them as poor as ratts,” and therefore refractory and unmanageable. Johnson says further: “There is another grand villain, George Clock, who lives by Conajoharie Castle, and robs the Indians of all their cloaths, etc.” The chiefs complained, “upon which I wrote him twice to give over that custom of selling liquor to the Indians; the answer was he gave the bearer, I might hang myself.”[7] Indian affairs, it will be seen, were no better regulated then than now.

[5: Report of a Council with the Indians at Albany, 28 June, 1754.]

[6: Answer of the Six [Five] Nations to His Excellency the Governor at Albany, 23 August, 1746.]

[7: Johnson to Clinton, 7 May, 1747.]

Meanwhile the French Indians were ravaging the frontiers and burning farmhouses to within sight of Albany. The Assembly offered rewards for the scalps of the marauders, but were slow in sending money to pay them, — to the great discontent of the Mohawks, who, however, at Johnson’s instigation, sent out various war-parties, two of which, accompanied by a few whites, made raids as far as the island of Montreal, and somewhat checked the incursions of the mission Indians by giving them work near home. The check was but momentary. Heathen Indians from the West joined the Canadian converts, and the frontiers of New York and New England, from the Mohawk to beyond the Kennebec, were stung through all their length by innumerable nocturnal surprises and petty attacks. The details of this murderous though ineffective partisan war would fill volumes if they were worth recording. One or two examples will show the nature of all.

In the valley of the little river Ashuelot, a New Hampshire affluent of the Connecticut, was a rude border-settlement which later years transformed into a town noted in rural New England for kindly hospitality, culture without pretense, and good-breeding without conventionality.[8] In 1746 the place was in all the rawness and ugliness of a backwoods hamlet. The rough fields, lately won from the virgin forest, showed here and there, among the stumps, a few log-cabins, roofed with slabs of pine, spruce, or hemlock. Near by was a wooden fort, made, no doubt, after the common frontier pattern, of a stockade fence ten or twelve feet high, enclosing cabins to shelter the settlers in case of alarm, and furnished at the corners with what were called flankers, which were boxes of thick plank large enough to hold two or more men, raised above the ground on posts, and pierced with loopholes, so that each face of the stockade could be swept by a flank fire. One corner of this fort at Ashuelot was, however, guarded by a solid blockhouse, or, as it was commonly called, a “mount.”

[8: Keene, originally called Upper Ashuelot. On the same stream, a few miles below, was a similar settlement, called Lower Ashuelot, — the germ of the present Swanzey. This, too, suffered greatly from Indian attacks.]

On the twenty-third of April a band of sixty, or, by another account, a hundred Indians, approached the settlement before daybreak, and hid in the neighboring thickets to cut off the men in the fort as they came out to their morning work. One of the men, Ephraim Dorman, chanced to go out earlier than the rest. The Indians did not fire on him, but, not to give an alarm, tried to capture or kill him without noise. Several of them suddenly showed themselves, on which he threw down his gun in pretended submission. One of them came up to him with hatchet raised; but the nimble and sturdy borderer suddenly struck him with his fist a blow in the head that knocked him flat, then snatched up his own gun, and, as some say, the blanket of the half-stunned savage also, sprang off, reached the fort unhurt, and gave the alarm. Some of the families of the place were living in the fort; but the bolder or more careless still remained in their farmhouses, and if nothing were done for their relief, their fate was sealed. Therefore, the men sallied in a body, and a sharp fight ensued, giving the frightened settlers time to take refuge within the stockade. It was not too soon, for the work of havoc had already begun. Six houses and a barn were on fire, and twenty-three cattle had been killed. The Indians fought fiercely, killed John Bullard, and captured Nathan Blake, but at last retreated; and after they were gone, the charred remains of several of them were found among the ruins of one of the burned cabins, where they had probably been thrown to prevent their being scalped.

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 23 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

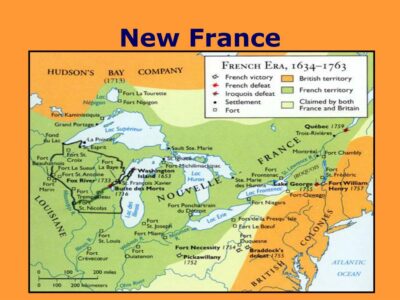

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.