From the East we turn to the West, for the province of New York passed for the West at that day.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 22.

La Corne called a council of war, and in view of the scarcity of food 200 and other reasons it was resolved to return to Beaubassin. Many of the French had fallen ill. Some of the sick and wounded were left at Grand Pré, others at Cobequid, and the Acadians were required to supply means of carrying the rest. Coulon’s party left Grand Pré on the twenty-third of February, and on the eighth of March reached Beaubassin.

La Corne called a council of war, and in view of the scarcity of food 200 and other reasons it was resolved to return to Beaubassin. Many of the French had fallen ill. Some of the sick and wounded were left at Grand Pré, others at Cobequid, and the Acadians were required to supply means of carrying the rest. Coulon’s party left Grand Pré on the twenty-third of February, and on the eighth of March reached Beaubassin.

[The dates are of the new style, which the French had adopted, while the English still clung to the old style.

By far the best account of this French victory at Mines is that of Beaujeu, in his Journal de la Campagne du Détachement de Canada à l’Acadie et aux Mines en 1746-47. It is preserved in the Archives de la Marine et des Colonies, and is printed in the documentary supplement of Le Canada Français, Vol. II. It supplies the means of correcting many errors and much confusion in some recent accounts of the affair. The report of Chevalier de la Corne, also printed in Le Canada Français, though much shorter, is necessary to a clear understanding of the matter. Letters of Lusignan fils to the minister Maurepas, 10 October, 1747, of Bishop Pontbriand (to Maurepas?), 10 July, 1747, and of Lusignan père to Maurepas, 10 October, 1747, give some additional incidents. The principal document on the English side is the report of Captain Benjamin Goldthwait, who succeeded Noble in command. A copy of the original, in the Public Record Office, is before me. The substance of it is correctly given in The Boston Post Boy of 2 March, 1747, and in N. E. Hist. Gen. Reg. x. 108. Various letters from Mascarene and Shirley (Public Record Office) contain accounts derived from returned officers and soldiers. The Notice of Colonel Arthur Noble, by William Goold (Collections Maine Historical Soc., 1881), may also be consulted.]

Ramesay did not fail to use the success at Grand Pré to influence the minds of the Acadians. He sent a circular letter to the inhabitants of the various districts, and especially to those of Mines, in which he told them that their country had been reconquered by the arms of the King of France, to whom he commanded them to be faithful subjects, holding no intercourse with the English under any pretense whatever, on pain of the severest punishment. “If,” he concludes, “we have withdrawn our soldiers from among you, it is for reasons known to us alone, and with a view to your advantage.”

[Ramesay aux Députés et Habitants des Mines, 31 Mars, 1747. At the end is written “A true copy, with the misspellings: signed W. Shirley.”]

Unfortunately for the effect of this message, Shirley had no sooner heard of the disaster at Grand Pré than he sent a body of Massachusetts soldiers to reoccupy the place.[1] This they did in April. The Acadians thus found themselves, as usual, between two dangers; and unable to see which horn of the dilemma was the worse, they tried to avoid both by conciliating French and English alike and assuring each of their devoted attachment. They sent a pathetic letter to Ramesay, telling him that their hearts were always French, and begging him at the same time to remember that they were a poor, helpless people, burdened with large families, and in danger of expulsion and ruin if they offended their masters, the English.[2] They wrote at the same time to Mascarene at Annapolis, sending him, to explain the situation, a copy of Ramesay’s threatening letter to them;[219] begging him to consider that they could not without danger dispense with answering it; at the same time they protested their entire fidelity to King George.[3]

[1: Shirley to Newcastle, 24 August, 1747.

[2: “Ainsis Monsieur nous vous prions de regarder notre bon Cœur et en même Temps notre Impuissance pauvre Peuple chargez la plus part de familles nombreuse point de Recours sil falois evacuer a quoy nous sommes menacez tous les jours qui nous tien dans une Crainte perpetuelle en nous voyant a la proximitet de nos maitre depuis un sy grand nombre dannes” (printed literatim). — Deputés des Mines à Ramesay, 24 Mai, 1747.]

[3: This probably explains the bad spelling of the letter, the copy before me having been made from the Acadian transcript sent to Mascarene, and now in the Public Record Office.]

[4: Les Habitants à l’honorable gouverneur au for d’anapolisse royal [sic], Mai (?), 1747.

On the 27th of June the inhabitants of Cobequid wrote again to Mascarene: “Monsieur nous prenons la Liberte de vous recrire celle icy pour vous assurer de nos tres humble Respect et d’un entiere Sou-mission a vos Ordres” (literatim).]

Ramesay, not satisfied with the results of his first letter, wrote again to the Acadians, ordering them, in the name of the governor-general of New France, to take up arms against the English, and enclosing for their instruction an extract from a letter of the French governor. “These,” says Ramesay, “are his words: ‘We consider ourself as master of Beaubassin and Mines, since we have driven off the English. Therefore there is no difficulty in forcing the Acadians to take arms for us; to which end we declare to them that they are discharged from the oath that they formerly took to the English, by which they are bound no longer, as has been decided by the authorities of Canada and Monseigneur our Bishop.’”

[“Nous nous regardons aujourdhuy Maistre de Beaubassin et des Mines puisque nous en avons Chassé les Anglois; ainsi il ny a aucune difficulté de forcer les Accadiens à prendre les armes pour nous, et de les y Contraindre; leur declarons à cet effêt qu’ils sont dechargé [sic] du Serment preté, cy devant, à l’Anglois, auquel ils ne sont plus obligé [sic] comme il y a été decidé par nos puissances de Canada et de Monseigneur notre Evesque” (literatim).]

[Ramesay aux Habitants de Chignecto, etc., 25 Mai, 1747.

A few months later, the deputies of Rivière-aux-Canards wrote to Shirley, thanking him for kindness which they said was undeserved, promising to do their duty thenceforth, but begging him to excuse them from giving up persons who had acted “contraire aux Interests de leur devoire,” representing the difficulty of their position, and protesting “une Soumission parfaite et en touts Respects.” The letter is signed by four deputies, of whom one writes his name, and three sign with crosses.]

The position of the Acadians was deplorable. By the Treaty of Utrecht, France had transferred them to the British Crown; yet French officers denounced them as rebels and threatened them with death if they did not fight at their bidding against England; and English officers threatened them with expulsion from the country if they broke their oath of allegiance to King George. It was the duty of the British ministry to occupy the province with a force sufficient to protect the inhabitants against French terrorism and leave no doubt that the King of England was master of Acadia in fact as well as in name. This alone could have averted the danger of Acadian revolt, and the harsh measures to which it afterwards gave rise. The ministry sent no aid but left to Shirley and Massachusetts the task of keeping the province for King George. Shirley and Massachusetts did what they could; but they could not do all that the emergency demanded.

Shirley courageously spoke his mind to the ministry, on whose favor he was dependent. “The fluctuating state of the inhabitants of Acadia,” he wrote to Newcastle, “seems, my lord, naturally to arise from their finding a want of due protection from his Majesty’s Government.”

[Shirley to Newcastle, 29 April, 1747.]

From the East we turn to the West, for the province of New York passed for the West at that day. Here a vital question was what would be the attitude of the Five Nations of the Iroquois towards the rival European colonies, their neighbors. The Treaty of Utrecht called them British subjects. What the word “subjects” meant, they themselves hardly knew. The English told them that it meant children; the French that it meant dogs and slaves. Events had tamed the fierce confederates; and now, though, like all savages, unstable as children, they leaned in their soberer moments to a position of neutrality between their European neighbors, watching with jealous eyes against the encroachments of both. The French would gladly have enlisted them and their tomahawks in the war; but seeing little hope of this, were generally content if they could prevent them from siding with the English, who on their part regarded them as their Indians, and were satisfied with nothing less than active alliance.

When Shirley’s plan for the invasion of Canada was afoot, Clinton, governor of New York, with much ado succeeded in convening the deputies of the confederacy at Albany, and by dint of speeches and presents induced them to sing the war-song and take up the hatchet for England. The Iroquois were disgusted when the scheme came to nought, their warlike ardor cooled, and they conceived a low opinion of English prowess.

The condition of New York as respects military efficiency was deplorable. She was divided against herself, and, as usual in such cases, party passion was stronger than the demands of war. The province was in the midst of one of those disputes with the representative of the Crown, which, in one degree or another, crippled or paralyzed the military activity of nearly all the British colonies. Twenty years or more earlier, when Massachusetts was at blows with the Indians on her borders, she suffered from the same disorders; but her governor and Assembly were of one mind as to urging on the war, and quarreled only on the questions in what way and under what command it should be waged. But in New York there was a strong party that opposed the war, being interested in the contraband trade long carried on with Canada. Clinton, the governor, had, too, an enemy in the person of the chief justice, James de Lancey, with whom he had had an after-dinner dispute, ending in a threat on the part of De Lancey that he would make the governor’s seat uncomfortable. To marked abilities, better education, and more knowledge of the world than was often found in the provinces, ready wit, and conspicuous social position, the chief justice joined a restless ambition and the arts of a demagogue.

He made good his threat, headed the opposition to the governor, and proved his most formidable antagonist. If either Clinton or Shirley had had the independent authority of a Canadian governor, the conduct of the war would have been widely different. Clinton was hampered at every turn. The Assembly held him at advantage; for it was they, and not the King, who paid his salary, and they could withhold or retrench it when he displeased them. The people sympathized with their representatives and backed them in opposition, — at least, when not under the stress of imminent danger.

A body of provincials, in the pay of the King, had been mustered at Albany for the proposed Canada expedition; and after that plan was abandoned, Clinton wished to use them for protecting the northern frontier and capturing that standing menace to the province, Crown Point. The Assembly, bent on crossing him at any price, refused to provide for transporting supplies farther than Albany. As the furnishing of provisions and transportation depended on that body, they could stop the movement of troops and defeat the governor’s military plans at their pleasure. In vain he told them, “If you deny me the necessary supplies, all my endeavors must become fruitless; I must wash my own hands, and leave at your doors the blood of the innocent people.”

[Extract from the Governor’s Message, in Smith, History of New York, ii. 124 (1830).]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 23 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

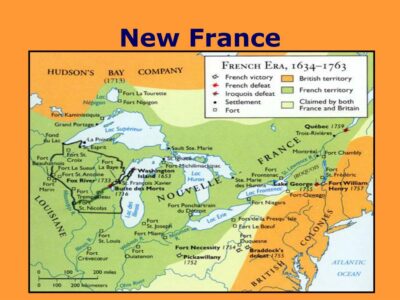

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.