No part of the country suffered more than the western borders of Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 23.

Before Dorman had given the alarm, an old woman, Mrs. McKenney, went from the fort to milk her cow in a neighboring barn. As she was returning, with her full milk-pail, a naked Indian was seen to spring from a clump of bushes, plunge a long knife into her back, and dart away without stopping to take the gray scalp of his victim. She tried feebly to reach the fort; but from age, corpulence, and a mortal wound she moved but slowly, and when a few steps from the gate, fell and died.

Before Dorman had given the alarm, an old woman, Mrs. McKenney, went from the fort to milk her cow in a neighboring barn. As she was returning, with her full milk-pail, a naked Indian was seen to spring from a clump of bushes, plunge a long knife into her back, and dart away without stopping to take the gray scalp of his victim. She tried feebly to reach the fort; but from age, corpulence, and a mortal wound she moved but slowly, and when a few steps from the gate, fell and died.

Ten days after, a party of Indians hid themselves at night by this same fort, and sent one of their number to gain admission under pretense of friendship, intending, no doubt, to rush in when the gate should be opened; but the man on guard detected the trick, and instead of opening the gate, fired through it, mortally wounding the Indian, on which his confederates made off. Again, at the same place, Deacon Josiah Foster, who had taken refuge in the fort, ventured out on a July morning to drive his cows to pasture. A gunshot was heard; and the men who went out to learn the cause, found the deacon lying in the wood-road, dead and scalped. An ambushed Indian had killed him and vanished. Such petty attacks were without number.

There is a French paper, called a record of “military movements,” which gives a list of war-parties sent from Montreal against the English border between the twenty-ninth of March, 1746, and the twenty-first of June in the same year. They number thirty-five distinct bands, nearly all composed of mission Indians living in or near the settled parts of Canada, — Abenakis, Iroquois of the Lake of Two Mountains and of Sault St. Louis (Caughnawaga), Algonquins of the Ottawa, and others, in parties rarely of more than thirty, and often of no more than six, yet enough for waylaying travelers or killing women in kitchens or cow-sheds, and solitary laborers in the fields. This record is accompanied by a list of wild Western Indians who came down to Montreal in the summer of 1746 to share in these “military movements.”

[Extrait sur les différents Mouvements Militaires qui se sont faits à Montréal à l’occasion de la Guerre, 1745, 1746. There is a translation in N. Y. Col. Docs.]

No part of the country suffered more than the western borders of Massachusetts and New Hampshire, and here were seen too plainly the evils of the prevailing want of concert among the British colonies. Massachusetts claimed extensive tracts north of her present northern boundary, and in the belief that her claim would hold good, had built a small wooden fort, called Fort Dummer, on the Connecticut, for the protection of settlers. New Hampshire disputed the title, and the question, being referred to the Crown, was decided in her favor. On this, Massachusetts withdrew the garrison of Fort Dummer and left New Hampshire to defend her own. This the Assembly of that province refused to do, on the ground that the fort was fifty miles from any settlement made by New Hampshire people, and was therefore useless to them, though of great value to Massachusetts as a cover to Northfield and other of her settlements lower down the Connecticut, to protect[1] which was no business of New Hampshire. But some years before, in 1740, three brothers, Samuel, David, and Stephen Farnsworth, natives of Groton, Massachusetts, had begun a new settlement on the Connecticut about forty-five miles north of the Massachusetts line and on ground which was soon to be assigned to New Hampshire. They were followed by five or six others. They acted on the belief that their settlement was within the jurisdiction of Massachusetts, and that she could and would protect them. The place was one of extreme exposure, not only from its isolation, far from help, but because it was on the banks of a wild and lonely river, the customary highway of war-parties on their descent from Canada. Number Four — for so the new settlement was called, because it was the fourth in a range of townships recently marked out along the Connecticut, but, with one or two exceptions, wholly unoccupied as yet — was a rude little outpost of civilization, buried in forests that spread unbroken to the banks of the St. Lawrence, while its nearest English neighbor was nearly thirty miles away. As may be supposed, it grew slowly, and in 1744 it had but nine or ten families. In the preceding year, when war seemed imminent, and it was clear that neither Massachusetts nor New Hampshire would lend a helping hand, the settlers of Number Four, seeing that their only resource was in themselves, called a meeting to consider the situation and determine what should be done. The meeting was held at the house, or log-cabin, of John Spafford, Jr., and being duly called to order, the following resolutions were adopted: that a fort be built at the charge of the proprietors of the said township of Number Four; that John Hastings, John Spafford, and John Avery be a committee to direct the building; that each carpenter be allowed nine shillings, old tenor, a day, each laborer seven shillings, and each pair of oxen three shillings and sixpence; that the proprietors of the township be taxed in the sum of three hundred pounds, old tenor, for building the fort; that John Spafford, Phineas Stevens, and John Hastings be assessors to assess the same, and Samuel Farnsworth collector to collect it.[2] And to the end that their fort should be a good and creditable one, they are said to have engaged the services of John Stoddard, accounted the foremost man of western Massachusetts, Superintendent of Defense, Colonel of Militia, Judge of Probate, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, a reputed authority in the construction of backwoods fortifications, and the admired owner of the only gold watch in Northampton.

[1: Journal of the Assembly of New Hampshire, quoted in Saunderson, History of Charlestown, N. H., 20.]

[2: Extracts from the Town Record, in Saunderson, History of Charlestown, N. H. (Number Four), 17, 18.]

Timber was abundant and could be had for the asking; for the frontiersman usually regarded a tree less as a valuable possession than as a natural enemy, to be got rid of by fair means or foul. The only cost was the labor. The fort rose rapidly. It was a square enclosing about three quarters of an acre, each side measuring a hundred and eighty feet. The wall was not of palisades, as was more usual, but of squared logs laid one upon another, and interlocked at the corners after the fashion of a log-cabin. Within were several houses, which had been built close together, for mutual protection, before the fort was begun, and which belonged to Stevens, Spafford, and other settlers. Apparently, they were small log-cabins; for they were valued at only from eight to thirty-five pounds each, in old tenor currency woefully attenuated by depreciation; and these sums being paid to the owners out of the three hundred pounds collected for building the fort, the cabins became public property. Either they were built in a straight line, or they were moved to form one, for when the fort was finished, they all backed against the outer wall, so that their low roofs served to fire from. The usual flankers completed the work, and the settlers of Number Four were so well pleased with it that they proudly declared their fort a better one than Fort Dummer, its nearest neighbor, which had been built by public authority at the charge of the province.

But a fort must have a garrison, and the ten or twelve men of Number Four would hardly be a sufficient one. Sooner or later an attack was certain; for the place was a backwoods Castle Dangerous, lying in the path of war-parties from Canada, whether coming down the Connecticut from Lake Memphremagog, or up Otter Creek from Lake Champlain, then over the mountains to Black River, and so down that stream, which would bring them directly to Number Four. New Hampshire would do nothing for them, and their only hope was in Massachusetts, of which most of them were natives, and which had good reasons for helping them to hold their ground, as a cover to its own settlements below. The governor and Assembly of Massachusetts did, in fact, send small parties of armed men from time to time to defend the endangered outpost, and the succor was timely; for though, during the first year of the war, Number Four was left in peace, yet from the nineteenth of April to the nineteenth of June, 1746, it was attacked by Indians five times, with some loss of scalps, and more of cattle, horses, and hogs. On the last occasion there was a hot fight in the woods, ending in the retreat of the Indians, said to have numbered a hundred and fifty, into a swamp, leaving behind them guns, blankets, hatchets, spears, and other things, valued at forty pounds, old tenor, — which, says the chronicle, “was reckoned a great booty for such beggarly enemies.”

[Saunderson, History of Charlestown, N. H. 29. Doolittle, Narrative of Mischief done by the Indian Enemy, — a contemporary chronicle.]

But Massachusetts grew tired of defending lands that had been adjudged to New Hampshire, and as the season drew towards an end, Number Four was left again to its own keeping. The settlers saw no choice but to abandon a place which they were too few to defend, and accordingly withdrew to the older settlements, after burying such of their effects as would bear it and leaving others to their fate. Six men, a dog, and a cat remained to keep the fort. Towards midwinter the human part of the garrison also withdrew, and the two uncongenial quadrupeds were left alone.

When the authorities of Massachusetts saw that a place so useful to bear the brunt of attack was left to certain destruction, they repented of their late withdrawal, and sent Captain Phineas Stevens, with thirty men, to reoccupy it. Stevens, a native of Sudbury, Massachusetts, one of the earliest settlers of Number Four, and one of its chief proprietors, was a bold, intelligent, and determined man, well fitted for the work before him. He and his band reached the fort on the twenty-seventh of March, 1747, and their arrival gave peculiar pleasure to its tenants, the dog and cat, the former of whom met them with lively demonstrations of joy. The pair had apparently lived in harmony, and found means of subsistence, as they are reported to have been in tolerable condition.

Stevens had brought with him a number of other dogs, — animals found useful for detecting the presence of Indians and tracking them to their lurking-places. A week or more after the arrival of the party, these canine allies showed great uneasiness and barked without ceasing; on which Stevens ordered a strict watch to be kept, and great precaution to be used in opening the gate of the fort. It was time, for the surrounding forest concealed what the New England chroniclers call an “army,” commanded by General Debeline. It scarcely need be said that Canada had no General Debeline, and that no such name is to be found in Canadian annals. The “army” was a large war-party of both French and Indians, and a French record shows that its commander was Boucher de Niverville, ensign in the colony troops.

[Extrait en forme de Journal de ce qui s’est passé d’intéressant dans la Colonie à l’occasion des Mouvements de Guerre, etc., 1746, 1747.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 23 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

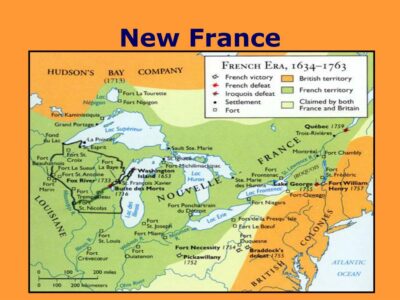

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.