Acadia was left to drift with the tide, as before.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 22.

The appearance of D’Anville’s fleet caused great excitement among the Acadians, who thought that they were about to pass again under the Crown of France. Fifty of them went on board the French ships at Chibucto to pilot them to the attack of Annapolis, and to their dismay found that no attack was to be made. When Ramesay, with his Canadians and Indians, took post at Chignecto and built a fort at Baye Verte, on the neck of the peninsula of Nova Scotia, the English power in that part of the colony seemed at an end. The inhabitants cut off all communication with Annapolis and detained the officers whom Mascarene sent for intelligence.

The appearance of D’Anville’s fleet caused great excitement among the Acadians, who thought that they were about to pass again under the Crown of France. Fifty of them went on board the French ships at Chibucto to pilot them to the attack of Annapolis, and to their dismay found that no attack was to be made. When Ramesay, with his Canadians and Indians, took post at Chignecto and built a fort at Baye Verte, on the neck of the peninsula of Nova Scotia, the English power in that part of the colony seemed at an end. The inhabitants cut off all communication with Annapolis and detained the officers whom Mascarene sent for intelligence.

From the first outbreak of the war it was evident that the French built their hopes of recovering Acadia largely on a rising of the Acadians against the English rule, and that they spared no efforts to excite such a rising. Early in 1745 a violent and cruel precaution against this danger was suggested. William Shirreff, provincial secretary, gave it as his opinion that the Acadians ought to be removed, being a standing menace to the colony.[1] This is the first proposal of such a nature that I find. Some months later, Shirley writes that, on a false report of the capture of Annapolis by the French, the Acadians sang Te Deum, and that every sign indicates that there will be an attempt in the spring to capture Annapolis, with their help.[2] Again, Shirley informs Newcastle that the French will get possession of Acadia unless the most dangerous of the inhabitants are removed, and English settlers put in their place.[3] He adds that there are not two hundred and twenty soldiers at Annapolis to defend the province against the whole body of Acadians and Indians, and he tells the minister that unless the expedition against Canada should end in the conquest of that country, the removal of some of the Acadians will be a necessity. He means those of Chignecto, who were kept in a threatening attitude by the presence of Ramesay and his Canadians, and who, as he thinks, had forfeited their lands by treasonable conduct. Shirley believes that families from New England might be induced to take their place, and that these, if settled under suitable regulations, would form a military frontier to the province of Nova Scotia “strong enough to keep the Canadians out,” and hold the Acadians to their allegiance.[4] The Duke of Bedford thinks the plan a good one, but objects to the expense.[5] Commodore Knowles, then governor of Louisbourg, who, being threatened with consumption and convinced that the climate was killing him, vented his feelings in strictures against everything and everybody, was of opinion that the Acadians, having broken their neutrality, ought to be expelled at once, and expresses the amiable hope that should his Majesty adopt this plan, he will charge him with executing it.[6]

[1: Shirreff to K. Gould, agent of Philips’s Regiment, March, 1745.]

[2: Shirley to Newcastle, 14 December, 1745.]

[3: Ibid., 10 May, 1746.]

[4: Ibid., 8 July, 1747.]

[5: Bedford to Newcastle, 11 September, 1747.]

[6: Knowles to Newcastle, 8 November, 1746.]

Shirley’s energetic nature inclined him to trenchant measures, and he had nothing of modern humanitarianism; but he was not inhuman, and he shrank from the cruelty of forcing whole communities into exile. While Knowles and others called for wholesale expatriation, he still held that it was possible to turn the greater part of the Acadians into safe subjects of the British Crown;[7] and to this end he advised the planting of a fortified town where Halifax now stands and securing by forts and garrisons the neck of the Acadian peninsula, where the population was most numerous and most disaffected. The garrisons, he thought, would not only impose respect, but would furnish the Acadians with what they wanted most, — ready markets for their produce, — and thus bind them to the British by strong ties of interest. Newcastle thought the plan good but wrote that its execution must be deferred to a future day. Three years later it was partly carried into effect by the foundation of Halifax; but at that time the disaffection of the Acadians had so increased, and the hope of regaining the province for France had risen so high, that this partial and tardy assertion of British authority only spurred the French agents to redoubled efforts to draw the inhabitants from the allegiance they had sworn to the Crown of England.

[7: Shirley says that the indiscriminate removal of the Acadians would be “unjust” and “too rigorous.” Knowles had proposed to put Catholic Jacobites from the Scotch Highlands into their place. Shirley thinks this inexpedient but believes that Protestants from Germany and Ulster might safely be trusted. The best plan of all, in his opinion, is that of “treating the Acadians as subjects, confining their punishment to the most guilty and dangerous among ’em, and keeping the rest in the country and endeavoring to make them useful members of society under his Majesty’s Government.” Shirley to Newcastle, 21 November, 1746. If the Newcastle Government had vigorously carried his recommendations into effect, the removal of the Acadians in 1755 would not have taken place.]

Shirley had also other plans in view for turning the Acadians into good British subjects. He proposed, as a measure of prime necessity, to exclude French priests from the province. The free exercise of their religion had been insured to the inhabitants by the Treaty of Utrecht, and on this point the English authorities had given no just cause of complaint. A priest had occasionally been warned, suspended, or removed; but without a single exception, so far as appears, this was in consequence of conduct which tended to excite disaffection, and which would have incurred equal or greater penalties in the case of a layman.[8] The sentence was directed, not against the priest, but against the political agitator. Shirley’s plan of excluding French priests from the province would not have violated the provisions of the treaty, provided that the inhabitants were supplied with other priests, not French subjects, and therefore not politically dangerous; but though such a measure was several times proposed by the provincial authorities, the exasperating apathy of the Newcastle Government gave no hope that it could be accomplished.

[8: There was afterwards sharp correspondence between Shirley and the governor of Canada touching the Acadian priests. Thus, Shirley writes: “I can’t avoid now, Sir, expressing great surprise at the other parts of your letter, whereby you take upon you to call Mr. Mascarene to account for expelling the missionary from Minas for being guilty of such treasonable practices within His Majesty’s government as merited a much severer Punishment.” Shirley à Galissonière, 9 Mai, 1749.

Shirley writes to Newcastle that the Acadians “are greatly under the influence of their priests, who continually receive their directions from the Bishop of Quebec, and are the instruments by which the governor of Canada makes all his attempts for the reduction of the province to the French Crown.” Shirley to Newcastle, 20 October, 1747. He proceeds to give facts in proof of his assertion. Compare “Montcalm and Wolfe,” i. 110, 111, 275, note.]

The influences most dangerous to British rule did not proceed from love of France or sympathy of race, but from the power of religion over a simple and ignorant people, trained in profound love and awe of their Church and its ministers, who were used by the representatives of Louis XV. as agents to alienate the Acadians from England.

The most strenuous of these clerical agitators was Abbé Le Loutre, missionary to the Micmacs, and after 1753 vicar-general of Acadia. He was a fiery and enterprising zealot, inclined by temperament to methods of violence, detesting the English, and restrained neither by pity nor scruple from using threats of damnation and the Micmac tomahawk to frighten the Acadians into doing his bidding. The worst charge against him, that of exciting the Indians of his mission to murder Captain Howe, an English officer, has not been proved; but it would not have been brought against him by his own countrymen if his character and past conduct had gained him their esteem.

The other Acadian priests were far from sharing Le Loutre’s violence; but their influence was always directed to alienating the inhabitants from their allegiance to King George. Hence Shirley regarded the conversion of the Acadians to Protestantism as a political measure of the first importance and proposed the establishment of schools in the province to that end. Thus far his recommendations are perfectly legitimate; but when he adds that rewards ought to be given to Acadians who renounce their faith, few will venture to defend him.

Newcastle would trouble himself with none of his schemes, and Acadia was left to drift with the tide, as before. “I shall finish my troubling your Grace upon the affairs of Nova Scotia with this letter,” writes the persevering Shirley. And he proceeds to ask, “as a proper Scheme for better securing the Subjection of the French inhabitants and Indians there,” that the governor and Council at Annapolis have special authority and direction from the King to arrest and examine such Acadians as shall be “most obnoxious and dangerous to his Majesty’s Government;” and if found guilty of treasonable correspondence with the enemy, to dispose of them and their estates in such manner as his Majesty shall order, at the same time promising indemnity to the rest for past offences, upon their taking or renewing the oath of allegiance.

[Shirley to Newcastle, 15 August, 1746.]

To this it does not appear that Newcastle made any answer except to direct Shirley, eight or nine months later, to tell the Acadians that, so long as they were peaceable subjects, they should be protected in property and religion.[9] Thus left to struggle unaided with a most difficult problem, entirely outside of his functions as governor of Massachusetts, Shirley did what he could. The most pressing danger, as he thought, rose from the presence of Ramesay and his Canadians at Chignecto; for that officer spared no pains to induce the Acadians to join him in another attempt against Annapolis, telling them that if they did not drive out the English, the English would drive them out. He was now at Mines, trying to raise the inhabitants in arms for France. Shirley thought it necessary to counteract him and force him and his Canadians back to the isthmus whence they had come; but as the ministry would give no soldiers, he was compelled to draw them from New England. The defense of Acadia was the business of the home government, and not of the colonies; but as they were deeply interested in the preservation of the endangered province, Massachusetts gave five hundred men in response to Shirley’s call, and Rhode Island and New Hampshire added, between them, as many more. Less than half of these levies reached Acadia. It was the stormy season. The Rhode Island vessels were wrecked near Martha’s Vineyard. A New Hampshire transport sloop was intercepted by a French armed vessel and ran back to Portsmouth. Four hundred and seventy men from Massachusetts, under Colonel Arthur Noble, were all who reached Annapolis, whence they sailed for Mines, accompanied by a few soldiers of the garrison. Storms, drifting ice, and the furious tides of the Bay of Fundy made their progress so difficult and uncertain that Noble resolved to finish the journey by land; and on the fourth of December he disembarked near the place now called French Cross, at the foot of the North Mountain, — a lofty barrier of rock and forest extending along the southern shore of the Bay of Fundy. Without a path and without guides, the party climbed the snow-encumbered heights and toiled towards their destination, each man carrying provisions for fourteen days in his haversack. After sleeping eight nights without shelter among the snowdrifts, they reached the Acadian village of Grand Pré, the chief settlement of the district of Mines. Ramesay and his Canadians were gone. On learning the approach of an English force, he had tried to persuade the Acadians that they were to be driven from their homes, and that their only hope was in joining with him to meet force by force; but they trusted Shirley’s recent assurance of protection, and replied that they would not break their oath of fidelity to King George. On this, Ramesay retreated to his old station at Chignecto, and Noble and his men occupied Grand Pré without opposition.

[9: Newcastle to Shirley, 30 May, 1747. Shirley had some time before directed Mascarene to tell the Acadians that while they behave peaceably and do not correspond with the enemy, their property will be safe, but that such as turn traitors will be treated accordingly. Shirley to Mascarene, 16 September, 1746.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 22 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

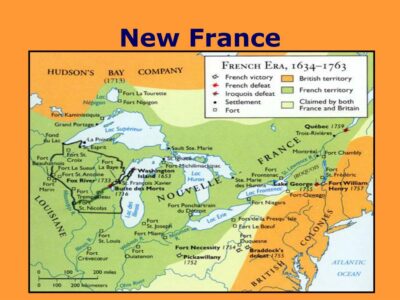

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.