Though the Acadians loved France, they were not always ready to sacrifice their interests to her.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 21.

After the storm of the fourteenth of September, provisions being almost spent, it was thought that there was no hope for “La Palme” and her crew but in giving up the enterprise and making all sail at once for home, since France now had no port of refuge on the western continent nearer than Quebec. Rations were reduced to three ounces of biscuit and three of salt meat a day; and after a time half of this pittance was cut off. There was diligent hunting for rats in the hold; and when this game failed, the crew, crazed with famine, demanded of their captain that five English prisoners who were on board should be butchered to appease the frenzy of their hunger. The captain consulted his officers, and they were of opinion that if he did not give his consent, the crew would work their will without it. The ship’s butcher was accordingly ordered to bind one of the prisoners, carry him to the bottom of the hold, put him to death, and distribute his flesh to the men in portions of three ounces each. The captain, walking the deck in great agitation all night, found a pretext for deferring the deed till morning, when a watchman sent aloft at daylight cried, “A sail!” The providential stranger was a Portuguese ship; and as Portugal was neutral in the war, she let the frigate approach to within hailing distance. The Portuguese captain soon came alongside in a boat, “accompanied,” in the words of the narrator, “by five sheep.” These were eagerly welcomed by the starving crew as agreeable substitutes for the five Englishmen; and, being forthwith slaughtered, were parceled out among the men, who would not wait till the flesh was cooked, but devoured it raw.[1] Provisions enough were obtained from the Portuguese to keep the frigate’s company alive till they reached Port Louis.

After the storm of the fourteenth of September, provisions being almost spent, it was thought that there was no hope for “La Palme” and her crew but in giving up the enterprise and making all sail at once for home, since France now had no port of refuge on the western continent nearer than Quebec. Rations were reduced to three ounces of biscuit and three of salt meat a day; and after a time half of this pittance was cut off. There was diligent hunting for rats in the hold; and when this game failed, the crew, crazed with famine, demanded of their captain that five English prisoners who were on board should be butchered to appease the frenzy of their hunger. The captain consulted his officers, and they were of opinion that if he did not give his consent, the crew would work their will without it. The ship’s butcher was accordingly ordered to bind one of the prisoners, carry him to the bottom of the hold, put him to death, and distribute his flesh to the men in portions of three ounces each. The captain, walking the deck in great agitation all night, found a pretext for deferring the deed till morning, when a watchman sent aloft at daylight cried, “A sail!” The providential stranger was a Portuguese ship; and as Portugal was neutral in the war, she let the frigate approach to within hailing distance. The Portuguese captain soon came alongside in a boat, “accompanied,” in the words of the narrator, “by five sheep.” These were eagerly welcomed by the starving crew as agreeable substitutes for the five Englishmen; and, being forthwith slaughtered, were parceled out among the men, who would not wait till the flesh was cooked, but devoured it raw.[1] Provisions enough were obtained from the Portuguese to keep the frigate’s company alive till they reached Port Louis.

[1: Relation du Voyage de Retour de M. Destrahoudal après la Tempête du 14 Septembre, in Journal historique.]

There are no sufficient means of judging how far the disasters of D’Anville’s fleet were due to a neglect of sanitary precautions or to deficient seamanship. Certain it is that there were many in self-righteous New England who would have held it impious to doubt that God had summoned the pestilence and the storm to fight the battles of his modern Israel.

Undaunted by disastrous failure, the French court equipped another fleet, not equal to that of D’Anville, yet still formidable, and placed it under La Jonquière, for the conquest of Acadia and Louisbourg. La Jonquière sailed from Rochelle on the tenth of May, 1747, and on the fourteenth was met by an English fleet stronger than his own and commanded by Admirals Anson and Warren. A fight ensued, in which, after brave resistance, the French were totally defeated. Six ships-of-war, including the flag-ship, were captured, with a host of prisoners, among whom was La Jonquière himself.

[Relation du Combat rendu le 14 Mai (new style), par l’Escadre du Roy commandée par M. de la Jonquière, in Le Canada Français, Supplément de Documents inédits, 33. Newcastle to Shirley, 30 May, 1747.]

Since the capture of Louisbourg, France had held constantly in view, as an object of prime importance, the recovery of her lost colony of Acadia. This was one of the chief aims of D’Anville’s expedition, and of that of La Jonquière in the next year. And to make assurance still more sure, a large body of Canadians, under M. de Ramesay, had been sent to Acadia to co-operate with D’Anville’s force; but the greater part of them had been recalled to aid in defending Quebec against the expected attack of the English. They returned when the news came that D’Anville was at Chibucto, and Ramesay, with a part of his command, advanced upon Port Royal, or Annapolis, in order to support the fleet in its promised attack on that place. He encamped at a little distance from the English fort, till he heard of the disasters that had ruined the fleet,[2] and then fell back to Chignecto, on the neck of the Acadian peninsula, where he made his quarters, with a force which, including Micmac, Malicite, and Penobscot Indians, amounted, at one time, to about sixteen hundred men.

[2: Journal de Beaujeu, in Le Canada Français, Documents, 53]

If France was bent on recovering Acadia, Shirley was no less resolved to keep it, if he could. In his belief, it was the key of the British American colonies, and again and again he urged the Duke of Newcastle to protect it. But Newcastle seems scarcely to have known where Acadia was, being ignorant of most things except the art of managing the House of Commons, and careless of all things that could not help his party and himself. Hence Shirley’s hyperboles, though never without a basis of truth, were lost upon him. Once, it is true, he sent three hundred men to Annapolis; but one hundred and eighty of them died on the voyage, or lay helpless in Boston hospitals, and the rest could better have been spared, some being recruits from English jails, and others Irish Catholics, several of whom deserted to the French, with information of the state of the garrison.

The defense of Acadia was left to Shirley and his Assembly, who in time of need sent companies of militia and rangers to Annapolis, and thus on several occasions saved it from returning to France. Shirley was the most watchful and strenuous defender of British interests on the continent; and in the present crisis British and colonial interests were one. He held that if Acadia were lost, the peace and safety of all the other colonies would be in peril; and in spite of the immense efforts made by the French court to recover it, he felt that the chief danger of the province was not from without, but from within. “If a thousand French troops should land in Nova Scotia,” he writes to Newcastle, “all the people would rise to join them, besides all the Indians.”[3] So, too, thought the French officials in America. The governor and intendant of Canada wrote to the colonial minister: “The inhabitants, with few exceptions, wish to return

under the French dominion, and will not hesitate to take up arms as soon as they see themselves free to do so; that is, as soon as we become masters of Port Royal, or they have powder and other munitions of war, and are backed by troops for their protection against the resentment of the English.”[4] Up to this time, however, though they had aided Duvivier in his attack on Annapolis so far as was possible without seeming to do so, they had not openly taken arms, and their refusal to fight for the besiegers is one among several causes to which Mascarene ascribes the success of his defense. While the greater part remained attached to France, some leaned to the English, who bought their produce and paid them in ready coin. Money was rare with the Acadians, who loved it, and were so addicted to hoarding it that the French authorities were led to speculate as to what might be the object of these careful savings.[5]

[3: Shirley to Newcastle, 29 October, 1745.]

[4: Beauharnois et Hocquart au Ministre, 12 Septembre, 1745.]

[5: Beauharnois et Hocquart au Ministre, 12 Septembre, 1745.]

Though the Acadians loved France, they were not always ready to sacrifice their interests to her. They would not supply Ramesay’s force with provisions in exchange for his promissory notes, but demanded hard cash.[6] This he had not to give, and was near being compelled to abandon his position in consequence. At the same time, in consideration of specie payment, the inhabitants brought in fuel for the English garrison at Louisbourg, and worked at repairing the rotten chevaux de frise of Annapolis.[7]

[6: Ibid.]

[7: Admiral Knowles à — 1746. Mascarene in Le Canada Français, Documents, 82.]

Mascarene, commandant at that place, being of French descent, was disposed at first to sympathize with the Acadians and treat them with a lenity that to the members of his council seemed neither fitting nor prudent. He wrote to Shirley: “The French inhabitants are certainly in a very perilous situation, those who pretend to be their friends and old masters having let loose a parcel of banditti to plunder them; whilst, on the other hand, they see themselves threatened with ruin if they fail in their allegiance to the British Government.”

[Mascarene, in Le Canada Français, Documents, 81.]

This unhappy people were in fact between two fires. France claimed them on one side, and England on the other, and each demanded their adhesion, without regard to their feelings or their welfare. The banditti of whom Mascarene speaks were the Micmac Indians, who were completely under the control of their missionary, Le Loutre, and were used by him to terrify the inhabitants into renouncing their English allegiance and actively supporting the French cause. By the Treaty of Utrecht France had transferred Acadia to Great Britain, and the inhabitants had afterwards taken an oath of fidelity to King George. Thus, they were British subjects; but as their oath had been accompanied by a promise, or at least a clear understanding, that they should not be required to take arms against Frenchmen or Indians, they had become known as the “Neutral French.” This name tended to perplex them, and in their ignorance and simplicity they hardly knew to which side they owed allegiance. Their illiteracy was extreme. Few of them could sign their names, and a contemporary well acquainted with them declares that he knew but a single Acadian who could read and write.[8] This was probably the notary, Le Blanc, whose compositions are crude and illiterate. Ignorant of books and isolated in a wild and remote corner of the world, the Acadians knew nothing of affairs, and were totally incompetent to meet the crisis that was soon to come upon them. In activity and enterprise they were far behind the Canadians, who looked on them as inferiors. Their pleasures were those of the humblest and simplest peasants; they were contented with their lot and asked only to be let alone. Their intercourse was unceremonious to such a point that they never addressed each other, or, it is said, even strangers, as monsieur. They had the social equality which can exist only in the humblest conditions of society, and presented the phenomenon of a primitive little democracy, hatched under the wing of an absolute monarchy. Each was as good as his neighbor; they had no natural leaders, nor any to advise or guide them, except the missionary priest, who in every case was expected by his superiors to influence them in the interest of France, and who, in fact, constantly did so. While one observer represents them as living in a state of primeval innocence, another describes both men and women as extremely foul of speech; from which he draws inferences unfavorable to their domestic morals,[9] which, nevertheless, were commendable. As is usual with a well-fed and unambitious peasantry, they were very prolific, and are said to have doubled their number every sixteen years. In 1748 they counted in the peninsula of Nova Scotia between twelve and thirteen thousand souls.[10] The English rule had been of the lightest, — so light that it could scarcely be felt; and this was not surprising, since the only instruments for enforcing it over a population wholly French were some two hundred disorderly soldiers in the crumbling little fort of Annapolis; and the province was left, perforce, to take care of itself.

[8: Moïse des Derniers, in Le Canada Français, i. 118.]

[9: Journal de Franquet, Part II.]

[10: Description de l’Acadie, avec le Nom des Paroisses et le Nombre des Habitants, 1748.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 22 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

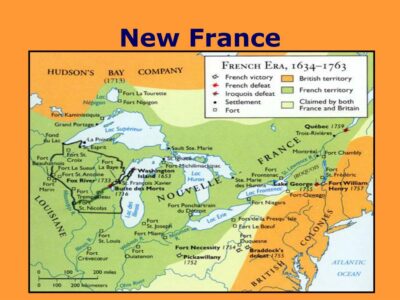

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.