At noon of that day, the storm still continuing, they marched again, though they could hardly see their way for the driving snow.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 22.

The village consisted of small, low wooden houses, scattered at intervals for the distance of a mile and a half, and therefore ill fitted for defense. The English had the frame of a blockhouse, or, as some say, of two blockhouses, ready to be set up on their arrival; but as the ground was hard frozen, it was difficult to make a foundation, and the frames were therefore stored in outbuildings of the village, with the intention of raising them in the spring. The vessels which had brought them; together with stores, ammunition, five small cannon, and a good supply of snowshoes, had just arrived at the landing-place, — and here, with incredible fatuity, were allowed to remain, with most of their indispensable contents still on board. The men, meanwhile, were quartered in the Acadian houses.

The village consisted of small, low wooden houses, scattered at intervals for the distance of a mile and a half, and therefore ill fitted for defense. The English had the frame of a blockhouse, or, as some say, of two blockhouses, ready to be set up on their arrival; but as the ground was hard frozen, it was difficult to make a foundation, and the frames were therefore stored in outbuildings of the village, with the intention of raising them in the spring. The vessels which had brought them; together with stores, ammunition, five small cannon, and a good supply of snowshoes, had just arrived at the landing-place, — and here, with incredible fatuity, were allowed to remain, with most of their indispensable contents still on board. The men, meanwhile, were quartered in the Acadian houses.

Noble’s position was critical, but he was assured that he could not be reached from Chignecto in such a bitter season; and this he was too ready to believe, though he himself had just made a march, which, if not so long, was quite as arduous. Yet he did not neglect every precaution but kept out scouting-parties to range the surrounding country, while the rest of his men took their ease in the Acadian houses, living on the provisions of the villagers, for which payment was afterwards made. Some of the inhabitants, who had openly favored Ramesay and his followers, fled to the woods, in fear of the consequences; but the greater part remained quietly in the village.

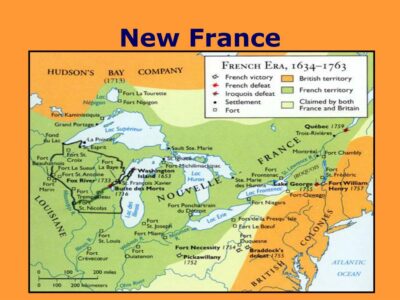

At the head of the Bay of Fundy its waters form a fork, consisting of Chignecto Bay on the one hand, and Mines Basin on the other. At the head of Chignecto Bay was the Acadian settlement of Chignecto, or Beaubassin, in the houses of which Ramesay had quartered his Canadians. Here the neck of the Acadian peninsula is at its narrowest, the distance across to Baye Verte, where Ramesay had built a fort, being little more than twelve miles. Thus, he controlled the isthmus, — from which, however, Noble hoped to dislodge him in the spring.

In the afternoon of the eighth of January an Acadian who had been sent to Mines by the missionary Germain, came to Beaubassin with the news that two hundred and twenty English were at Grand Pré, and that more were expected.[1] Ramesay instantly formed a plan of extraordinary hardihood, and resolved, by a rapid march and a night attack, to surprise the new-comers. His party was greatly reduced by disease, and to recruit it he wrote to La Corne, Récollet missionary at Miramichi, to join him with his Indians; writing at the same time to Maillard, former colleague of Le Loutre at the mission of Shubenacadie, and to Girard, priest of Cobequid, to muster Indians, collect provisions, and gather information concerning the English. Meanwhile his Canadians busied themselves with making snowshoes and dog-sledges for the march.

[1: Beaujeu, Journal de la Campagne du Détachement de Canada à l’Acadie, in Le Canada Français, ii. Documents, 16.]

Ramesay could not command the expedition in person, as an accident to one of his knees had disabled him from marching. This was less to be regretted, in view of the quality of his officers, for he had with him the flower of the warlike Canadian noblesse, — Coulon de Villiers, who, seven years later, defeated Washington at Fort Necessity; Beaujeu, the future hero of the Monongahela, in appearance a carpet knight, in reality a bold and determined warrior; the Chevalier de la Corne, a model of bodily and mental hardihood; Saint-Pierre, Lanaudière, Saint-Ours, Desligneris, Courtemanche, Repentigny, Boishébert, Gaspé, Colombière, Marin, Lusignan, — all adepts in the warfare of surprise and sudden onslaught in which the Canadians excelled.

Coulon de Villiers commanded in Ramesay’s place; and on the twenty-first of January he and the other officers led their men across the isthmus from Beaubassin to Baye Verte, where they all encamped in the woods, and where they were joined by a party of Indians and some Acadians from Beaubassin and Isle St. Jean.[2] Provisions, ammunition, and other requisites were distributed, and at noon of the twenty-third they broke up their camp, marched three leagues, and bivouacked towards evening. On the next morning they marched again at daybreak. There was sharp cold, with a storm of snow, — not the large, moist, lazy flakes that fall peacefully and harmlessly, but those small crystalline particles that drive spitefully before the wind and prick the cheek like needles. It was the kind of snowstorm called in Canada la poudrerie. They had hoped to make a long day’s march; but feet and faces were freezing, and they were forced to stop, at noon, under such shelter as the thick woods of pine, spruce, and fir could supply. In the morning they marched again, following the border of the sea, their dog-teams dragging provisions and baggage over the broken ice of creeks and inlets, which they sometimes avoided by hewing paths through the forest. After a day of extreme fatigue, they stopped at the small bay where the town of Wallace now stands. Beaujeu says: “While we were digging out the snow to make our huts, there came two Acadians with letters from MM. Maillard and Girard.” The two priests sent a mixture of good and evil news. On one hand the English were more numerous than had been reported; on the other, they had not set up the blockhouses they had brought with them. Some Acadians of the neighboring settlement joined the party at this camp, as also did a few Indians.

[2: Mascarene to Shirley, 8 February, 1746 (1747, new style).]

On the next morning, January 27, the adventurers stopped at the village of Tatmagouche, where they were again joined by a number of Acadians. After mending their broken sledges they resumed their march, and at five in the afternoon reached a place called Bacouel, at the beginning of the portage that led some twenty-five miles across the country to Cobequid, now Truro, at the head of Mines Basin. Here they were met by Girard, priest of Cobequid, from whom Coulon exacted a promise to meet him again at that village in two days. Girard gave the promise unwillingly, fearing, says Beaujeu, to embroil himself with the English authorities. He reported that the force at Grand Pré counted at least four hundred and fifty, or, as some said, more than five hundred. This startling news ran through the camp; but the men were not daunted. “The more there are,” they said, “the more we shall kill.”

The party spent the twenty-eighth in mending their damaged sledges, and in the afternoon they were joined by more Acadians and Indians. Thus reinforced, they marched again, and towards evening reached a village on the outskirts of Cobequid. Here the missionary Maillard joined them, — to the great satisfaction of Coulon, who relied on him and his brother priest Girard to procure supplies of provisions. Maillard promised to go himself to Grand Pré with the Indians of his mission.

The party rested for a day, and set out again on the first of February, stopped at Maillard’s house in Cobequid for the provisions he had collected for them, and then pushed on towards the river Shubenacadie, which runs from the south into Cobequid Bay, the head of Mines Basin. When they reached the river they found it impassable from floating ice, which forced them to seek a passage at some distance above. Coulon was resolved, however, that at any risk a detachment should cross at once, to stop the roads to Grand Pré, and prevent the English from being warned of his approach; for though the Acadians inclined to the French, and were eager to serve them when the risk was not too great, there were some of them who, from interest or fear, were ready to make favor with the English by carrying them intelligence. Boishébert, with ten Canadians, put out from shore in a canoe, and were near perishing among the drifting ice; but they gained the farther shore at last, and guarded every path to Grand Pré. The main body filed on snowshoes up the east bank of the Shubenacadie, where the forests were choked with snow and encumbered with fallen trees, over which the sledges were to be dragged, to their great detriment. On this day, the third, they made five leagues; on the next only two, which brought them within half a league of Le Loutre’s Micmac mission. Not far from this place the river was easily passable on the ice, and they continued their march westward across the country to the river Kennetcook by ways so difficult that their Indian guide lost the path, and for a time led them astray. On the seventh, Boishébert and his party rejoined them, and brought a reinforcement of 189 sixteen Indians, whom the Acadians had furnished with arms. Provisions were failing, till on the eighth, as they approached the village of Pisiquid, now Windsor, the Acadians, with great zeal, brought them a supply. They told them, too, that the English at Grand Pré were perfectly secure, suspecting no danger.

On the ninth, in spite of a cold, dry storm of snow, they reached the west branch of the river Avon. It was but seven French leagues to Grand Pré, which they hoped to reach before night; but fatigue compelled them to rest till the tenth. At noon of that day, the storm still continuing, they marched again, though they could hardly see their way for the driving snow. They soon came to a small stream, along the frozen surface of which they drew up in order, and, by command of Coulon, Beaujeu divided them all into ten parties, for simultaneous attacks on as many houses occupied by the English. Then, marching slowly, lest they should arrive too soon, they reached the river Gaspereau, which enters Mines Basin at Grand Pré. They were now but half a league from their destination. Here they stopped an hour in the storm, shivering and half frozen, waiting for nightfall. When it grew dark, they moved again, and soon came to a number of houses on the riverbank. Each of the ten parties took possession of one of these, making great fires to warm themselves and dry their guns.

It chanced that in the house where Coulon and his band sought shelter, a wedding-feast was going on. The guests were much startled at this sudden irruption of armed men; but to the Canadians and their chief the festival was a stroke of amazing good luck, for most of the guests were inhabitants of Grand Pré, who knew perfectly the houses occupied by the English, and could tell with precision where the officers were quartered. This was a point of extreme importance. The English were distributed among twenty-four houses, scattered, as before mentioned, for the distance of a mile and a half.[3] The assailants were too few to attack all these houses at once; but if those where the chief officers lodged could be surprised and captured with their inmates, the rest could make little resistance. Hence it was that Coulon had divided his followers into ten parties, each with one or more chosen officers; these officers were now called together at the house of the interrupted festivity, and the late guests having given full information as to the position of the English quarters and the military quality of their inmates, a special object of attack was assigned to the officer of each party, with Acadian guides to conduct him to it. The principal party, consisting of fifty, or, as another account says, of seventy-five men, was led by Coulon himself, with Beaujeu, Desligneris, Mercier, Léry, and Lusignan as his officers. This party was to attack a stone house near the middle of the village, where the main guard was stationed, — a building somewhat larger than the rest, and the only one at all suited for defense. The second party of forty men, commanded by La Corne, with Rigauville, Lagny, and Villemont, was to attack a neighboring house, the quarters of Colonel Noble, his brother, Ensign Noble, and several other officers. The remaining parties, of twenty-five men each according to Beaujeu, or twenty-eight according to La Corne, were to make a dash, as nearly as possible at the same time, at other houses which it was thought most important to secure. All had Acadian guides, whose services in that capacity were invaluable; though Beaujeu complains that they were of no use in the attack. He says that the united force was about three hundred men, while the English Captain Goldthwait puts it, including Acadians and Indians, at from five to six hundred. That of the English was a little above five hundred in all. Every arrangement being made, and his part assigned to each officer, the whole body was drawn up in the storm, and the chaplain pronounced a general absolution. Then each of the ten parties, guided by one or more Acadians, took the path for its destination, every man on snowshoes, with the lock of his gun well sheltered under his capote.

[3: Goldthwait to Shirley, 2 March, 1746 (1747). Captain Benjamin Goldthwait was second in command of the English detachment.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 22 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.