Thus ended one of the most gallant exploits in French-Canadian annals.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 22.

The largest party, under Coulon, was, as we have seen, to attack the stone house in the middle of the village; but their guide went astray, and about three in the morning they approached a small wooden house not far from their true object. A guard was posted here, as at all the English quarters. The night was dark and the snow was still falling, as it had done without ceasing for the past thirty hours. The English sentinel descried through the darkness and the storm what seemed the shadows of an advancing crowd of men. He cried, “Who goes there?” and then shouted, “To arms!” A door was flung open, and the guard appeared in the entrance. But at that moment the moving shadows vanished from before the eyes of the sentinel. The French, one and all, had thrown themselves flat in the soft, light snow, and nothing was to be seen or heard. The English thought it a false alarm, and the house was quiet again. Then Coulon and his men rose and dashed forward. Again, in a loud and startled voice, the sentinel shouted, “To arms!” A great light, as of a blazing fire, shone through the open doorway, and men were seen within in hurried movement. Coulon, who was in the front, said to Beaujeu, who was close at his side, that the house was not the one they were to attack. Beaujeu replied that it was no time to change, and Coulon dashed forward again. Beaujeu aimed at the sentinel and shot him dead. There was the flash and report of muskets from the house, and Coulon dropped in the snow, severely wounded. The young cadet, Lusignan, was hit in the shoulder; but he still pushed on, when a second shot shattered his thigh. “Friends,” cried the gallant youth, as he fell by the side of his commander, “don’t let two dead men discourage you.” The Canadians, powdered from head to foot with snow, burst into the house. Within ten minutes, all resistance was overpowered. Of twenty-four Englishmen, twenty-one were killed, and three made prisoners.

The largest party, under Coulon, was, as we have seen, to attack the stone house in the middle of the village; but their guide went astray, and about three in the morning they approached a small wooden house not far from their true object. A guard was posted here, as at all the English quarters. The night was dark and the snow was still falling, as it had done without ceasing for the past thirty hours. The English sentinel descried through the darkness and the storm what seemed the shadows of an advancing crowd of men. He cried, “Who goes there?” and then shouted, “To arms!” A door was flung open, and the guard appeared in the entrance. But at that moment the moving shadows vanished from before the eyes of the sentinel. The French, one and all, had thrown themselves flat in the soft, light snow, and nothing was to be seen or heard. The English thought it a false alarm, and the house was quiet again. Then Coulon and his men rose and dashed forward. Again, in a loud and startled voice, the sentinel shouted, “To arms!” A great light, as of a blazing fire, shone through the open doorway, and men were seen within in hurried movement. Coulon, who was in the front, said to Beaujeu, who was close at his side, that the house was not the one they were to attack. Beaujeu replied that it was no time to change, and Coulon dashed forward again. Beaujeu aimed at the sentinel and shot him dead. There was the flash and report of muskets from the house, and Coulon dropped in the snow, severely wounded. The young cadet, Lusignan, was hit in the shoulder; but he still pushed on, when a second shot shattered his thigh. “Friends,” cried the gallant youth, as he fell by the side of his commander, “don’t let two dead men discourage you.” The Canadians, powdered from head to foot with snow, burst into the house. Within ten minutes, all resistance was overpowered. Of twenty-four Englishmen, twenty-one were killed, and three made prisoners.

[Beaujeu, Journal.]

Meanwhile, La Corne, with his party of forty men, had attacked the house where were quartered Colonel Noble and his brother, with Captain Howe and several other officers. Noble had lately transferred the main guard to the stone house, but had not yet removed thither himself, and the guard in the house which he occupied was small. The French burst the door with axes, and rushed in. Colonel Noble, startled from sleep, sprang from his bed, receiving two musket-balls in the body as he did so. He seems to have had pistols, for he returned the fire several times. His servant, who was in the house, testified that the French called to the colonel through a window and promised him quarter if he would surrender; but that he refused, on which they fired again, and a bullet, striking his forehead, killed him instantly. His brother, Ensign Noble, was also shot down, fighting in his shirt. Lieutenants Pickering and Lechmere lay in bed dangerously ill and were killed there. Lieutenant Jones, after, as the narrator says, “ridding himself of some of the enemy,” tried to break through the rest and escape, but was run through the heart with a bayonet. Captain Howe was severely wounded and made prisoner.

Coulon and Lusignan, disabled by their wounds, were carried back to the houses on the Gaspereau, where the French surgeon had remained. Coulon’s party, now commanded by Beaujeu, having met and joined the smaller party under Lotbinière, proceeded to the aid of others who might need their help; for while they heard a great noise of musketry from far and near, and could discern bodies of men in motion here and there, they could not see whether these were friends or foes, or discern which side fortune favored. They presently met the party of Marin, composed of twenty-five Indians, who had just been repulsed with loss from the house which they had attacked. By this time there was a gleam of daylight, and as they plodded wearily over the snowdrifts, they no longer groped in darkness. The two parties of Colombière and Boishébert soon joined them, with the agreeable news that each had captured a house; and the united force now proceeded to make a successful attack on two buildings where the English had stored the frames of their blockhouses. Here the assailants captured ten prisoners. It was now broad day, but they could not see through the falling snow whether the enterprise, as a whole, had prospered or failed. Therefore, Beaujeu sent Marin to find La Corne, who, in the absence of Coulon, held the chief command. Marin was gone two hours. At length he returned and reported that the English in the houses which had not been attacked, together with such others as had not been killed or captured, had drawn together at the stone house in the middle of the village, that La Corne was blockading them there, and that he ordered Beaujeu and his party to join him at once. When Beaujeu reached the place, he found La Corne posted at the house where Noble had been killed, and which was within easy musket-shot of the stone house occupied by the English, against whom a spattering fire was kept up by the French from the cover of neighboring buildings. Those in the stone house returned the fire; but no great harm was done on either side, till the English, now commanded by Captain Goldthwait, attempted to recapture the house where La Corne and his party were posted. Two companies made a sally; but they had among them only eighteen pairs of snowshoes, the rest having been left on board the two vessels which had brought the stores of the detachment from Annapolis, and which now lay moored hard by, in the power of the enemy, at or near the mouth of the Gaspereau. Hence the sallying

party floundered helpless among the drifts, plunging so deep in the dry snow that they could not use their guns and could scarcely move, while bullets showered upon them from La Corne’s men in the house, and others hovering about them on snowshoes. The attempt was hopeless, and after some loss the two companies fell back. The firing continued, as before, till noon, or, according to Beaujeu, till three in the afternoon, when a French officer, carrying a flag of truce, came out of La Corne’s house. The occasion of the overture was this.

Captain Howe, who, as before mentioned, had been badly wounded at the capture of this house, was still there, a prisoner, without surgical aid, the French surgeon being at the houses on the Gaspereau, in charge of Coulon and other wounded men. “Though,” says Beaujeu, “M. Howe was a firm man, he begged the Chevalier La Corne not to let him bleed to death for want of aid but permit him to send for an English surgeon.” To this La Corne, after consulting with his officers, consented, and Marin went to the English with a white flag and a note from Howe explaining the situation. The surgeon was sent, and Howe’s wound was dressed, Marin remaining as a hostage. A suspension of arms took place till the surgeon’s return; after which it was prolonged till nine o’clock of the next morning, at the instance, according to French accounts, of the English, and, according to English accounts, of the French. In either case, the truce was welcome to both sides. The English, who were in the stone house to the number of nearly three hundred and fifty, crowded to suffocation, had five small cannon, two of which were four-pounders, and three were swivels; but these were probably not in position, as it does not appear that any use was made of them. There was no ammunition except what the men had in their powder-horns and bullet-pouches, the main stock having been left, with other necessaries, on board the schooner and sloop now in the hands of the French. It was found, on examination, that they had ammunition for eight shots each, and provisions for one day. Water was only to be had by bringing it from a neighboring brook. As there were snowshoes for only about one man in twenty, sorties were out of the question; and the house was commanded by high ground on three sides.

Though their number was still considerable, their position was growing desperate. Thus, it happened that when the truce expired, Goldthwait, the English commander, with another officer, who seems to have been Captain Preble, came with a white flag to the house where La Corne was posted, and proposed terms of capitulation, Howe, who spoke French, acting as interpreter. La Corne made proposals on his side, and as neither party was anxious to continue the fray, they soon came to an understanding.

It was agreed that within forty-eight hours the English should march for Annapolis with the honors of war; that the prisoners taken by the French should remain in their hands; that the Indians, who had been the only plunderers, should keep the plunder they had taken; that the English sick and wounded should be left, till their recovery, at the neighboring settlement of Rivière-aux-Canards, protected by a French guard, and that the English engaged in the affair at Grand Pré should not bear arms during the next six months within the district about the head of the Bay of Fundy, including Chignecto, Grand Pré, and the neighboring settlements.

Captain Howe was released on parole, with the condition that he should send back in exchange one Lacroix, a French prisoner at Boston, — “which,” says La Corne, “he faithfully did.”

Thus ended one of the most gallant exploits in French-Canadian annals. As respects the losses on each side, the French and English accounts are irreconcilable; nor are the statements of either party consistent with themselves. Mascarene reports to Shirley that seventy English were killed, and above sixty captured; though he afterwards reduces these numbers, having, as he says, received farther information. On the French side he says that four officers and about forty men were killed, and that many wounded were carried off in carts during the fight. Beaujeu, on the other hand, sets the English loss at one hundred and thirty killed, fifteen wounded, and fifty captured; and the French loss at seven killed and fifteen wounded. As for the numbers engaged, the statements are scarcely less divergent. It seems clear, however, that when Coulon began his march from Baye Verte, his party consisted of about three hundred Canadians and Indians, without reckoning some Acadians who had joined him from Beaubassin and Isle St. Jean. Others joined him on the way to Grand Pré, counting a hundred and fifty according to Shirley, — which appears to be much too large an estimate. The English, by their own showing, numbered five hundred, or five hundred and twenty-five. Of eleven houses attacked, ten were surprised and carried, with the help of the darkness and storm and the skillful management of the assailants.

“No sooner was the capitulation signed,” says Beaujeu, “than we became in appearance the best of friends.” La Corne directed military honors to be rendered to the remains of the brothers Noble; and in all points the Canadians, both officers and men, treated the English with kindness and courtesy. “The English commandant,” again says Beaujeu, “invited us all to dine with him and his officers, so that we might have the pleasure of making acquaintance over a bowl of punch.” The repast being served after such a fashion as circumstances permitted, victors and vanquished sat down together; when, says Beaujeu, “we received on the part of our hosts many compliments on our polite manners and our skill in making war.” And the compliments were well deserved.

At eight o’clock on the morning of the fourteenth of February the English filed out of the stone house, and with arms shouldered, drums beating, and colors flying, marched between two ranks of the French, and took the road for Annapolis. The English sick and wounded were sent to the settlement of Rivière-aux-Canards, where, protected by a French guard and attended by an English surgeon, they were to remain till able to reach the British fort.

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 22 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

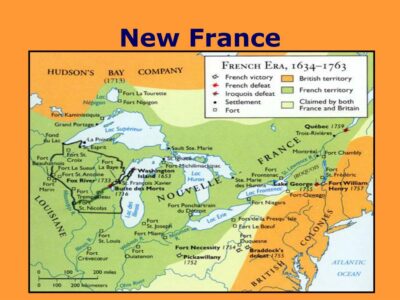

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.