Nothing could be more dismal than the condition of Louisbourg, as reflected in the diaries of soldiers and others who spent there the winter that followed its capture.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 20.

A question vital to Massachusetts worried her in the midst of her triumph. She had been bankrupt for many years, and of the large volume of her outstanding obligations, a part was not worth eight pence in the pound. Added to her load of debt, she had spent £183,649 sterling on the Louisbourg expedition. That which Smollett calls “the most important achievement of the war” would never have taken place but for her, and Old England, and not New, was to reap the profit; for Louisbourg, conquered by arms, was to be restored by diplomacy. If the money she had spent for the mother-country were not repaid, her ruin was certain. William Bollan, English by birth and a son-in-law of Shirley, was sent out to urge the just claim of the province, and after long and vigorous solicitation, he succeeded. The full amount, in sterling value, was paid to Massachusetts, and the expenditures of New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island were also reimbursed.[1] The people of Boston saw twenty-seven of those long unwieldy trucks which many elders of the place still remember as used in their youth, rumbling up King Street to the treasury, loaded with two hundred and seventeen chests of Spanish dollars, and a hundred barrels of copper coin. A pound sterling was worth eleven pounds of the old-tenor currency of Massachusetts, and thirty shillings of the new-tenor. Those beneficent trucks carried enough to buy in at a stroke nine-tenths of the old-tenor notes of the province, — nominally worth above two millions. A stringent tax, laid on by the Assembly, paid the remaining tenth, and Massachusetts was restored to financial health.[2]

A question vital to Massachusetts worried her in the midst of her triumph. She had been bankrupt for many years, and of the large volume of her outstanding obligations, a part was not worth eight pence in the pound. Added to her load of debt, she had spent £183,649 sterling on the Louisbourg expedition. That which Smollett calls “the most important achievement of the war” would never have taken place but for her, and Old England, and not New, was to reap the profit; for Louisbourg, conquered by arms, was to be restored by diplomacy. If the money she had spent for the mother-country were not repaid, her ruin was certain. William Bollan, English by birth and a son-in-law of Shirley, was sent out to urge the just claim of the province, and after long and vigorous solicitation, he succeeded. The full amount, in sterling value, was paid to Massachusetts, and the expenditures of New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island were also reimbursed.[1] The people of Boston saw twenty-seven of those long unwieldy trucks which many elders of the place still remember as used in their youth, rumbling up King Street to the treasury, loaded with two hundred and seventeen chests of Spanish dollars, and a hundred barrels of copper coin. A pound sterling was worth eleven pounds of the old-tenor currency of Massachusetts, and thirty shillings of the new-tenor. Those beneficent trucks carried enough to buy in at a stroke nine-tenths of the old-tenor notes of the province, — nominally worth above two millions. A stringent tax, laid on by the Assembly, paid the remaining tenth, and Massachusetts was restored to financial health.[2]

[1: £183,649 to Massachusetts; £16,355 to New Hampshire; £28,863 to Connecticut; £6,332 to Rhode Island.]

[2: Palfrey, New England, v. 101-109; Shirley, Report to the Board of Trade Bollan to Secretary Willard, in Coll. Mass. Hist. Soc., i. 53; Hutchinson, Hist. Mass., ii. 391-395. Letters of Bollan in Massachusetts Archives.]

It was through the exertions of the much-abused Thomas Hutchinson, Speaker of the Assembly and historian of Massachusetts, that the money was used for the laudable purpose of extinguishing the old debt.

Shirley did his utmost to support Bollan in his efforts to obtain compensation, and after highly praising the zeal and loyalty of the people of his province, he writes to Newcastle: “Justice, as well as the affection which I bear to ’em, constrains me to beseech your Grace to recommend their Case to his Majesty’s paternal Care & Tenderness in the Strongest manner.” — Shirley to Newcastle, 6 November, 1745.

The English documents on the siege of Louisbourg are many and voluminous. The Pepperrell Papers and the Belknap Papers, both in the library of the Massachusetts Historical Society, afford a vast number of contemporary letters and documents on the subject. The large volume entitled Siege of Louisbourg, in the same repository, contains many more, including a number of autograph diaries of soldiers and others. To these are to be added the journals of General Wolcott, James Gibson, Benjamin Cleaves, Seth Pomeroy, and several others, in print or manuscript, among which is especially to be noted the journal appended to Shirley’s Letter to the Duke of Newcastle of October 28, 1745, and bearing the names of Pepperrell, Brigadier Waldo, Colonel Moore, and Lieutenant-Colonels Lothrop and Gridley, who attest its accuracy. Many papers have also been drawn from the Public Record Office of London.

Accounts of this affair have hitherto rested, with but slight exceptions, on English sources alone. The archives of France have furnished useful material to the foregoing narrative, notably the long report of the governor, Duchambon, to the minister of war, and the letter of the intendant, Bigot, to the same personage, within about six weeks after the surrender. But the most curious French evidence respecting the siege is the Lettre d’un Habitant de Louisbourg contenant une Relation exacte & circonstanciée de la Prise de l’Isle-Royale par les Anglois. A Québec, chez Guillaume le Sincère, à l’Image de la Vérité, 1745. This little work, of eighty-one printed pages, is extremely rare. I could study it only by having a literatim transcript made from the copy in the Bibliothèque Nationale, as it was not in the British Museum. It bears the signature B. L. N., and is dated à … ce 28 Août, 1745. The imprint of Québec, etc., is certainly a mask, the book having no doubt been printed in France. It severely criticises Duchambon, and makes him mainly answerable for the disaster.

The troops and inhabitants of Louisbourg were all embarked for France, and the town was at last in full possession of the victors. The serious-minded among them — and there were few who did not bear the stamp of hereditary Puritanism — now saw a fresh proof that they were the peculiar care of an approving Providence. While they were in camp the weather had been favorable; but they were scarcely housed when a cold, persistent rain poured down in floods that would have drenched their flimsy tents and turned their huts of turf into mud-heaps, robbing the sick of every hope of recovery. Even now they got little comfort from the shattered tenements of Louisbourg. The siege had left the town in so filthy a condition that the wells were infected and the water was poisoned.

The soldiers clamored for discharge, having enlisted to serve only till the end of the expedition; and Shirley insisted that faith must be kept with them, or no more would enlist.[3] Pepperrell, much to the dissatisfaction of Warren, sent home about seven hundred men, some of whom were on the sick list, while the rest had families in distress and danger on the exposed frontier. At the same time he begged hard for reinforcements, expecting a visit from the French and a desperate attempt to recover Louisbourg. He and Warren governed the place jointly, under martial law, and they both passed half their time in holding courts-martial; for disorder reigned among the disgusted militia, and no less among the crowd of hungry speculators, who flocked like vultures to the conquered town to buy the cargoes of captured ships, or seek for other prey. The Massachusetts soldiers, whose pay was the smallest, and who had counted on being at their homes by the end of July, were the most turbulent; but all alike were on the brink of mutiny. Excited by their ringleaders, they one day marched in a body to the parade and threw down their arms, but probably soon picked them up again, as in most cases the guns were hunting-pieces belonging to those who carried them. Pepperrell begged Shirley to come to Louisbourg and bring the mutineers back to duty. Accordingly, on the sixteenth of August he arrived in a ship-of-war, accompanied by Mrs. Shirley and Mrs. Warren, wife of the commodore. The soldiers duly fell into line to receive him. As it was not his habit to hide his own merits, he tells the Duke of Newcastle that nobody but he could have quieted the malcontents, — which is probably true, as nobody else had power to raise their pay. He made them a speech, promised them forty shillings in Massachusetts new-tenor currency a month, instead of twenty-five, and ended with ordering for each man half a pint of rum to drink the King’s health. Though potations so generous might be thought to promise effects not wholly sedative, the mutineers were brought to reason, and some even consented to remain in garrison till the next June.[4]

[3: Shirley to Newcastle, 27 September, 1745.]

[4: Shirley to Newcastle, 4 December, 1745.]

Small reinforcements came from New England to hold the place till the arrival of troops from Gibraltar, promised by the ministry. The two regiments raised in the colonies, and commanded by Shirley and Pepperrell, were also intended to form a part of the garrison; but difficulty was found in filling the ranks, because, says Shirley, some commissions have been given to Englishmen, and men will not enlist, here except under American officers.

Nothing could be more dismal than the condition of Louisbourg, as reflected in the diaries of soldiers and others who spent there the winter that followed its capture. Among these diaries is that of the worthy Benjamin Crafts, private in Hale’s Essex regiment, who to the entry of each day adds a pious invocation, sincere in its way, no doubt, though hackneyed, and sometimes in strange company. Thus, after noting down Shirley’s gift of half a pint of rum to every man to drink the King’s health, he adds immediately: “The Lord Look upon us and enable us to trust in him & may he prepare us for his holy Day.” On “September ye 1, being Sabath,” we find the following record: “I am much out of order. This forenoon heard Mr. Stephen Williams preach from ye 18 Luke 9 verse in the afternoon from ye 8 of Ecles: 8 verse: Blessed be the Lord that has given us to enjoy another Sabath and opertunity to hear his Word Dispensed.” On the next day, “being Monday,” he continues, “Last night I was taken very Bad: the Lord be pleased to strengthen my inner man that I may put my whole Trust in him. May we all be prepared for his holy will. Rcd part of plunder, 9 small tooth combs.” Crafts died in the spring, of the prevailing distemper, after doing good service in the commissary department of his regiment.

Stephen Williams, the preacher whose sermons had comforted Crafts in his trouble, was a son of Rev. John Williams, captured by the Indians at Deerfield in 1704, and was now minister of Long Meadow, Massachusetts. He had joined the anti-papal crusade as one of its chaplains, and passed for a man of ability, — a point on which those who read his diary will probably have doubts. The lot of the army chaplains was of the hardest. A pestilence had fallen upon Louisbourg and turned the fortress into a hospital. “After we got into the town,” says the sarcastic Dr. Douglas, whose pleasure it is to put everything in its worst light,

a sordid indolence or sloth, for want of discipline, induced putrid fevers and dysenteries, which at length in August became contagious, and the people died like rotten sheep.” From fourteen to twenty-seven were buried every day in the cemetery behind the town, outside the Maurepas Gate, by the old lime-kiln on Rochefort Point; and the forgotten bones of above five hundred New England men lie there to this day under the coarse, neglected grass. The chaplain’s diary is little but a dismal record of sickness, death, sermons, funerals, and prayers with the dying ten times a day. “Prayed at Hospital; — Prayed at Citadel; — Preached at Grand Batery; — Visited Capt. [illegible], very sick; — One of Capt. — — ’s company dy^d. — Am but poorly myself, but able to keep about.” Now and then there is a momentary change of note, as when he writes: “July 29^{th}. One of ye Captains of ye men of war caind a soldier who struck ye capt. again. A great tumult. Swords were drawn; no life lost, but great uneasiness is caused.” Or when he sets down the “say” of some Briton, apparently a naval officer, “that he had tho’t ye New England men were Cowards — but now he tho’t yt if they had a pick axe & spade, they w’d dig ye way to Hell & storm it.”

[The autograph diary of Rev. Stephen Williams is in my possession. The handwriting is detestable.]

Williams was sorely smitten with homesickness, but he sturdily kept his post, in spite of grievous yearnings for family and flock. The pestilence slowly abated, till at length the burying-parties that passed the Maurepas Gate counted only three or four a day. At the end of January five hundred and sixty-one men had died, eleven hundred were on the sick list, and about one thousand fit for duty.[5] The promised regiments from Gibraltar had not come. Could the French have struck then, Louisbourg might have changed hands again. The Gibraltar regiments had arrived so late upon that rude coast that they turned southward to the milder shores of Virginia, spent the winter there, and did not appear at Louisbourg till April. They brought with them a commission for Warren as governor of the fortress. He made a speech of thanks to the New England garrison, now reduced to less than nineteen hundred men, sick and well, and they sailed at last for home, Louisbourg being now thought safe from any attempt of France.

[5: On May 10, 1746, Shirley writes to Newcastle that eight hundred and ninety men had died during the winter. The sufferings of the garrison from cold were extreme.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 21 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

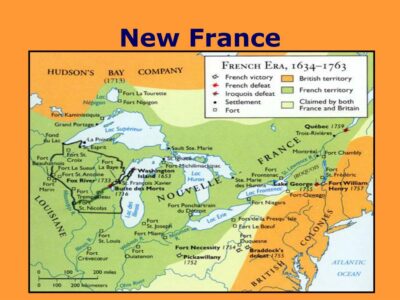

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.