Astounding tidings reached New England and startled her like a thunder-clap from dreams of conquest.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 21.

To the zealous and energetic Shirley the capture of the fortress was but a beginning of greater triumphs. Scarcely had the New England militia sailed from Boston on their desperate venture, when he wrote to the Duke of Newcastle that should the expedition succeed, all New England would be on fire to attack Canada, and the other colonies would take part with them, if ordered to do so by the ministry.[1] And, some months later, after Louisbourg was taken, he urged the policy of striking while the iron was hot, and invading Canada at once. The colonists, he said, were ready, and it would be easier to raise ten thousand men for such an attack than one thousand to lie idle in garrison at Louisbourg or anywhere else. France and England, he thinks, cannot live on the same continent. If we were rid of the French, he continues, England would soon control America, which would make her first among the nations; and he ventures what now seems the modest prediction that in one or two centuries the British colonies would rival France in population. Even now, he is sure that they would raise twenty thousand men to capture Canada, if the King required it of them, and Warren would be an acceptable commander for the naval part of the expedition; “but,” concludes the governor, “I will take no step without orders from his Majesty.”[2]

To the zealous and energetic Shirley the capture of the fortress was but a beginning of greater triumphs. Scarcely had the New England militia sailed from Boston on their desperate venture, when he wrote to the Duke of Newcastle that should the expedition succeed, all New England would be on fire to attack Canada, and the other colonies would take part with them, if ordered to do so by the ministry.[1] And, some months later, after Louisbourg was taken, he urged the policy of striking while the iron was hot, and invading Canada at once. The colonists, he said, were ready, and it would be easier to raise ten thousand men for such an attack than one thousand to lie idle in garrison at Louisbourg or anywhere else. France and England, he thinks, cannot live on the same continent. If we were rid of the French, he continues, England would soon control America, which would make her first among the nations; and he ventures what now seems the modest prediction that in one or two centuries the British colonies would rival France in population. Even now, he is sure that they would raise twenty thousand men to capture Canada, if the King required it of them, and Warren would be an acceptable commander for the naval part of the expedition; “but,” concludes the governor, “I will take no step without orders from his Majesty.”[2]

[1: Shirley to Newcastle, 4 April, 1745.]

[2: Ibid., 29 October, 1745.]

The Duke of Newcastle was now at the head of the Government. Smollett and Horace Walpole have made his absurdities familiar, in anecdotes which, true or not, do no injustice to his character; yet he had talents that were great in their way, though their way was a mean one. They were talents, not of the statesman, but of the political manager, and their object was to win office and keep it.

Newcastle, whatever his motives, listened to the counsels of Shirley, and directed him to consult with Warren as to the proposed attack on Canada. At the same time he sent a circular letter to the governors of the provinces from New England to North Carolina, directing them, should the invasion be ordered, to call upon their assemblies for as many men as they would grant.[3] Shirley’s views were cordially supported by Warren, and the levies were made accordingly, though not in proportion to the strength of the several colonies; for those south of New York felt little interest in the plan. Shirley was told to “dispose Massachusetts to do its part;” but neither he nor his province needed prompting. Taking his cue from the Roman senator, he exclaimed to his Assembly, “Delenda est Canada;” and the Assembly responded by voting to raise thirty-five hundred men, and offering a bounty equivalent to £4 sterling to each volunteer, besides a blanket for everyone and a bed for every two. New Hampshire contributed five hundred men, Rhode Island three hundred, Connecticut one thousand, New York sixteen hundred, New Jersey five hundred, Maryland three hundred, and Virginia one hundred. The Pennsylvania Assembly, controlled by Quaker noncombatants, would give no soldiers; but, by a popular movement, the province furnished four hundred men, without the help of its representatives.[4]

[3: Newcastle to the Provincial Governors, 14 March, 1746; Shirley to Newcastle, 31 May, 1746; Proclamation of Shirley, 2 June, 1746.]

[4: Hutchinson, ii. 381, note. Compare Memoirs of the Principal Transactions of the Last War.]

As usual in the English attempts against Canada, the campaign was to be a double one. The main body of troops, composed of British regulars and New England militia, was to sail up the St. Lawrence and attack Quebec, while the levies of New York and the provinces farther south, aided, it was hoped, by the warriors of the Iroquois, were to advance on Montreal by way of Lake Champlain.

Newcastle promised eight battalions of British troops under Lieutenant-General Saint-Clair. They were to meet the New England men at Louisbourg, and all were then to sail together for Quebec, under the escort of a squadron commanded by Warren. Shirley also was to go to Louisbourg and arrange the plan of the campaign with the general and the admiral. Thus, without loss of time, the captured fortress was to be made a base of operations against its late owners.

Canada was wild with alarm at reports of English preparation. There were about fifty English prisoners in barracks at Quebec, and every device was tried to get information from them; but being chiefly rustics caught on the frontiers by Indian war-parties, they had little news to give, and often refused to give even this. One of them, who had been taken long before and gained over by the French,[5] was used as an agent to extract information from his countrymen and was called “notre homme de confiance.” At the same time the prisoners were freely supplied with writing materials, and their letters to their friends being then opened, it appeared that they were all in expectation of speedy deliverance.[6]

[4: “Un ancien prisonnier affidé que l’on a mis dans nos interests.”]

[5: Extrait en forme de Journal de ce qui s’est passé dans la Colonie depuis … le 1 Décembre, 1745, jusqu’au 9 Novembre, 1746, signé Beauharnois et Hocquart.]

In July a report came from Acadia that from forty to fifty thousand men were to attack Canada; and on the first of August a prisoner lately taken at Saratoga declared that there were thirty-two warships at Boston ready to sail against Quebec, and that thirteen thousand men were to march at once from Albany against Montreal. “If all these stories are true,” writes the Canadian journalist, “all the English on this continent must be in arms.”

Preparations for defense were pushed with feverish energy. Fireships were made ready at Quebec, and fire-rafts at Isle-aux-Coudres; provisions were gathered, and ammunition was distributed; reconnoitering parties were sent to watch the gulf and the river; and bands of

Canadians and Indians lately sent to Acadia were ordered to hasten back.

Thanks to the Duke of Newcastle, all these alarms were needless. The Massachusetts levies were ready within six weeks, and Shirley, eager and impatient, waited in vain for the squadron from England and the promised eight battalions of regulars. They did not come; and in August he wrote to Newcastle that it would now be impossible to reach Quebec before October, which would be too late.[6] The eight battalions had been sent to Portsmouth for embarkation, ordered on board the transports, then ordered ashore again, and finally sent on an abortive expedition against the coast of France. There were those who thought that this had been their destination from the first, and that the proposed attack on Canada was only a pretense to deceive the enemy. It was not till the next spring that Newcastle tried to explain the miscarriage to Shirley. He wrote that the troops had been detained by headwinds till General Saint-Clair and Admiral Lestock thought it too late; to which he added that the demands of the European war made the Canadian expedition impracticable, and that Shirley was to stand on the defensive and attempt no further conquests. As for the provincial soldiers, who this time were in the pay of the Crown, he says that they were “very expensive,” and orders the governor to get rid of them “as cheap as possible.”[7] Thus, not for the first time, the hopes of the colonies were brought to nought by the failure of the British ministers to keep their promises.

[6: Shirley to Newcastle, 22 August, 1746.]

[7: Newcastle to Shirley, 30 May, 1747.]

When, in the autumn of 1746, Shirley said that for the present Canada was to be let alone, he bethought him of a less decisive conquest, and proposed to employ the provincial troops for an attack on Crown Point, which formed a halfway station between Albany and Montreal, and was the constant rendezvous of war-parties against New York, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, whose discords and jealousies had prevented them from combining to attack it. The Dutch of Albany, too, had strong commercial reasons for not coming to blows with the Canadians. Of late, however, Massachusetts and New York had suffered so much from this inconvenient neighbor that it was possible to unite them against it; and as Clinton, governor of New York, was scarcely less earnest to get possession of Crown Point than was Shirley himself, a plan of operations was soon settled. By the middle of October fifteen hundred Massachusetts troops were on their way to join the New York levies, and then advance upon the obnoxious post.

[Memoirs of the Principal Transactions of the Last War.]

Even this modest enterprise was destined to fail. Astounding tidings reached New England and startled her like a thunderclap from dreams of conquest. It was reported that a great French fleet and army were on their way to retake Louisbourg, reconquer Acadia, burn Boston, and lay waste the other seaboard towns. The Massachusetts troops marching for Crown Point were recalled, and the country militia were mustered in arms. In a few days the narrow, crooked streets of the Puritan capital were crowded with more than eight thousand armed rustics from the farms and villages of Middlesex, Essex, Norfolk, and Worcester, and Connecticut promised six thousand more as soon as the hostile fleet should appear. The defenses of Castle William were enlarged and strengthened, and cannon were planted on the islands at the mouth of the harbor; hulks were sunk in the channel, and a boom was laid across it under the guns of the castle.[8] The alarm was compared to that which filled England on the approach of the Spanish Armada.[9]

[8: Shirley to Newcastle, 29 September, 1746. Shirley says that though the French may bombard the town, he does not think they could make a landing, as he shall have fifteen thousand good men within call to oppose them.]

[9: Hutchinson, ii. 382.]

Canada heard the news of the coming armament with an exultation that was dashed with misgiving as weeks and months passed and the fleet did not appear. At length in September a vessel put in to an Acadian harbor with the report that she had met the ships in mid-ocean, and that they counted a hundred and fifty sail. Some weeks later the governor and intendant of Canada wrote that on the fourteenth of October they received a letter from Chibucto with “the agreeable news” that the Duc d’Anville and his fleet had arrived there about three weeks before. Had they known more, they would have rejoiced less.

That her great American fortress should have been snatched from her by a despised militia was more than France could bear; and in the midst of a burdensome war, she made a crowning effort to retrieve her honor and pay the debt with usury. It was computed that nearly half the French navy was gathered at Brest under command of the Duc d’Anville. By one account his force consisted of eleven ships-of-the-line, twenty frigates, and thirty-four transports and fireships, or sixty-five in all. Another list gives a total of sixty-six, of which ten were ships-of-the-line, twenty-two were frigates and fireships, and thirty-four were transports.[10] These last carried the regiment of Ponthieu, with other veteran troops, to the number in all of three thousand one hundred and fifty. The fleet was to be joined at Chibucto, now Halifax, by four heavy ships-of-war lately sent to the West Indies under M. de Conflans.

[10: This list is in the journal of a captured French officer called by Shirley M. Rebateau.]

From Brest D’Anville sailed for some reason to Rochelle, and here the ships were kept so long by headwinds that it was the twentieth of June before they could put to sea. From the first the omens were sinister. The admiral was beset with questions as to the destination of the fleet, which was known to him alone; and when, for the sake of peace, he told it to his officers, their discontent redoubled. The Bay of Biscay was rough and boisterous, and spars, sails, and bowsprits were carried away. After they had been a week at sea, some of the ships, being dull sailers, lagged behind, and the rest were forced to shorten sail and wait for them. In the longitude of the Azores there was a dead calm, and the whole fleet lay idle for days. Then came a squall, with lightning. Several ships were struck. On one of them six men were killed, and on the seventy-gun ship “Mars” a box of musket and cannon cartridges blew up, killed ten men, and wounded twenty-one. A store-ship which proved to be sinking was abandoned and burned. Then a pestilence broke out, and in some of the ships there were more sick than in health.

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 21 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

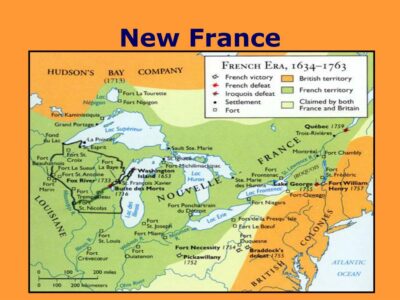

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.