All these operations were accomplished with the utmost ardor and energy but with a scorn of rule and precedent that astonished and bewildered the French.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 19.

The English occupation of the Grand Battery may be called the decisive event of the siege. There seems no doubt that the French could have averted the disaster long enough to make it of little help to the invaders. The waterfront of the battery was impregnable. The rear defenses consisted of a loopholed wall of masonry, with a ditch ten feet deep and twelve feet wide, and also a covered way and glacis, which General Wolcott describes as unfinished. In this he mistook. They were not unfinished, but had been partly demolished, with a view to reconstruction. The rear wall was flanked by two towers, which, says Duchambon, were demolished; but General Wolcott declares that swivels were still mounted on them,[1] and he adds that “two hundred men might hold the battery against five thousand without cannon.” The English landed their cannon near Flat Point; and before they could be turned against the Grand Battery, they must be dragged four miles over hills and rocks, through spongy marshes and jungles of matted evergreens. This would have required a week or more. The alternative was an escalade, in which the undisciplined assailants would no doubt have met a bloody rebuff. Thus, this Grand Battery, which, says Wolcott, “is in fact a fort,” might at least have been held long enough to save the munitions and stores, and effectually disable the cannon, which supplied the English with the only artillery they had, competent to the work before them. The hasty abandonment of this important post was not Duchambon’s only blunder, but it was the worst of them all.

The English occupation of the Grand Battery may be called the decisive event of the siege. There seems no doubt that the French could have averted the disaster long enough to make it of little help to the invaders. The waterfront of the battery was impregnable. The rear defenses consisted of a loopholed wall of masonry, with a ditch ten feet deep and twelve feet wide, and also a covered way and glacis, which General Wolcott describes as unfinished. In this he mistook. They were not unfinished, but had been partly demolished, with a view to reconstruction. The rear wall was flanked by two towers, which, says Duchambon, were demolished; but General Wolcott declares that swivels were still mounted on them,[1] and he adds that “two hundred men might hold the battery against five thousand without cannon.” The English landed their cannon near Flat Point; and before they could be turned against the Grand Battery, they must be dragged four miles over hills and rocks, through spongy marshes and jungles of matted evergreens. This would have required a week or more. The alternative was an escalade, in which the undisciplined assailants would no doubt have met a bloody rebuff. Thus, this Grand Battery, which, says Wolcott, “is in fact a fort,” might at least have been held long enough to save the munitions and stores, and effectually disable the cannon, which supplied the English with the only artillery they had, competent to the work before them. The hasty abandonment of this important post was not Duchambon’s only blunder, but it was the worst of them all.

[1: Journal of Major-General Wolcott.]

On the night after their landing, the New England men slept in the woods, wet or dry, with or without blankets, as the case might be, and in the morning set themselves to encamping with as much order as they were capable of. A brook ran down from the hills and entered the sea two miles or more from the town. The ground on each side, though rough, was high and dry, and here most of the regiments made their quarters, — Willard’s, Moulton’s, and Moore’s on the east side, and Burr’s and Pepperrell’s on the west. Those on the east, in some cases, saw fit to extend themselves towards Louisbourg as far as the edge of the intervening marsh, but were soon forced back to a safer position by the cannonballs of the fortress, which came bowling amongst them. This marsh was that green, flat sponge of mud and moss that stretched from this point to the glacis of Louisbourg.

There was great want of tents, for material to make them was scarce in New England. Old sails were often used instead, being stretched over poles, — perhaps after the fashion of a Sioux teepee. When these could not be had, the men built huts of sods, with roofs of spruce-boughs overlapping like a thatch; for at that early season, bark would not peel from the trees. The landing of guns, munitions, and stores was a formidable task, consuming many days and destroying many boats, as happened again when Amherst landed his cannon at this same place. Large flat boats, brought from Boston, were used for the purpose, and the loads were carried ashore on the heads of the men, wading through ice-cold surf to the waist, after which, having no change of clothing, they slept on the ground through the chill and foggy nights, reckless of future rheumatisms.

[The author of The Importance and Advantage of Cape Breton says: “When the hardships they were exposed to come to be considered, the behavior of these men will hardly gain credit. They went ashore wet, had no [dry] clothes to cover them, were exposed in this condition to cold, foggy nights, and yet cheerfully underwent these difficulties for the sake of executing a project they had voluntarily undertaken.”]

A worse task was before them. The cannon were to be dragged over the marsh to Green Hill, a spur of the line of rough heights that half encircled the town and harbor. Here the first battery was to be planted; and from this point other guns were to be dragged onward to more advanced stations, — a distance in all of more than two miles, thought by the French to be impassable. So, in fact, it seemed; for at the first attempt, the wheels of the cannon sank to the hubs in mud and moss, then the carriage, and finally the piece itself slowly disappeared. Lieutenant-Colonel Meserve, of the New Hampshire regiment, a shipbuilder by trade, presently overcame the difficulty. By his direction sledges of timber were made, sixteen feet long and five feet wide; a cannon was placed on each of these, and it was then dragged over the marsh by a team of two hundred men, harnessed with rope-traces and breast-straps, and wading to the knees. Horses or oxen would have foundered in the mire. The way had often to be changed, as the mossy surface was soon churned into a hopeless slough along the line of march. The work could be done only at night or in thick fog, the men being completely exposed to the cannon of the town. Thirteen years after, when General Amherst besieged Louisbourg again, he dragged his cannon to the same hill over the same marsh; but having at his command, instead of four thousand militiamen, eleven thousand British regulars, with all appliances and means to boot, he made a road, with prodigious labor, through the mire, and protected it from the French shot by an epaulement, or lateral earthwork.

[See “Montcalm and Wolfe,” chap. xix.]

Pepperrell writes in ardent words of the cheerfulness of his men “under almost incredible hardships.” Shoes and clothing failed, till many were in tatters and many barefooted;[2] yet they toiled on with unconquerable spirit, and within four days had planted a battery of 106 six guns on Green Hill, which was about a mile from the King’s Bastion of Louisbourg. In

another week they had dragged four twenty-two-pound cannon and ten coehorns — gravely called “cowhorns” by the bucolic Pomeroy — six or seven hundred yards farther and planted them within easy range of the citadel. Two of the cannon burst, and were replaced by four more and a large mortar, which burst in its turn, and Shirley was begged to send another. Meanwhile a battery, chiefly of coehorns, had been planted on a hillock four hundred and forty yards from the West Gate, where it greatly annoyed the French; and on the next night an advanced battery was placed just opposite the same gate, and scarcely two hundred and fifty yards from it. This West Gate, the principal gate of Louisbourg, opened upon the tract of high, firm ground that lay on the left of the besiegers, between the marsh and the harbor, an arm of which here extended westward beyond the town, into what was called the Barachois, a salt pond formed by a projecting spit of sand. On the side of the Barachois farthest from the town was a hillock on which stood the house of an habitant named Martissan. Here, on the twentieth of May, a fifth battery was planted, consisting of two of the French forty-two-pounders taken in the Grand Battery, to which three others were afterwards added. Each of these heavy pieces was dragged to its destination by a team of three hundred men over rough and rocky ground swept by the French artillery. This fifth battery, called the Northwest, or Titcomb’s, proved most destructive to the fortress.[3]

[2: Pepperrell to Newcastle, 28 June, 1745.]

[3: Journal of the Siege, appended to Shirley’s report to Newcastle; Duchambon au Ministre, 2 Septembre, 1745; Lettre d’un Habitant; Pomeroy, etc.]

All these operations were accomplished with the utmost ardor and energy, but with a scorn of rule and precedent that astonished and bewildered the French. The raw New England men went their own way, laughed at trenches and zigzags, and persisted in trusting their lives to the night and the fog. Several writers say that the English engineer Bastide tried to teach them discretion; but this could hardly be, for Bastide, whose station was Annapolis, did not reach Louisbourg till the fifth of June, when the batteries were finished, and the siege was nearly ended. A recent French writer makes the curious assertion that it was one of the ministers, or army chaplains, who took upon him the vain task of instruction in the art of war on this occasion.

[Ferland, Cours d’Histoire du Canada, ii. 477. “L’ennemi ne nous attaquoit point dans les formes, et ne pratiquoit point aucun retranchement pour se couvrir.” — Habitant de Louisbourg.]

This ignorant and self-satisfied recklessness might have cost the besiegers dear if the French, instead of being perplexed and startled at the novelty of their proceedings, had taken advantage of it; but Duchambon and some of his officers, remembering the mutiny of the past winter, feared to make sorties, lest the soldiers might desert or take part with the enemy. The danger of this appears to have been small. Warren speaks with wonder in his letters of the rarity of desertions, of which there appear to have been but three during the siege, — one being that of a half-idiot, from whom no information could be got. A bolder commander would not have stood idle while his own cannon were planted by the enemy to batter down his walls; and whatever the risks of a sortie, the risks of not making one were greater. “Both troops and militia eagerly demanded it, and I believe it would have succeeded,” writes the intendant, Bigot.[4] The attempt was actually made more than once in a half-hearted way, — notably on the eighth of May, when the French attacked the most advanced battery, and were repulsed, with little loss on either side.

[4: Bigot au Ministre, 1 Août, 1745.]

The Habitant de Louisbourg says: “The enemy did not attack us with any regularity and made no intrenchments to cover themselves.” This last is not exact. Not being wholly demented, they made intrenchments, such as they were, — at least, at the advanced battery;[5] as they would otherwise have been swept out of existence, being under the concentrated fire of several French batteries, two of which were within the range of a musket-shot.

[5: Diary of Joseph Sherburn, Captain at the Advanced Battery.]

The scarcity of good gunners was one of the chief difficulties of the besiegers. As privateering, and piracy also, against Frenchmen and Spaniards was a favorite pursuit in New England, there were men in Pepperrell’s army who knew how to handle cannon; but their number was insufficient, and the general sent a note to Warren, begging that he would lend him a few experienced gunners to teach their trade to the raw hands at the batteries. Three or four were sent, and they found apt pupils.

Pepperrell placed the advanced battery in charge of Captain Joseph[6] Sherburn, telling him to enlist as many gunners as he could. On the next day Sherburn reported that he had found six, one of whom seems to have been sent by Warren. With these and a number of raw men he repaired to his perilous station, where “I found,” he says, “a very poor intrenchment. Our best shelter from the French fire, which was very hot, was hogsheads filled with earth.” He and his men made the West Gate their chief mark; but before they could get a fair sight of it, they were forced to shoot down the fish-flakes, or stages for drying cod, that obstructed the view. Some of their party were soon killed, — Captain Pierce by a cannonball, Thomas Ash by a “bumb,” and others by musketry. In the night they improved their defenses, and mounted on them three more guns, one of eighteen-pound caliber, and the others of forty-two, — French pieces dragged from the Grand Battery, a mile and three quarters round the Barachois.

[6: He signs his name Jos. Sherburn; but in a list of the officers of the New Hampshire Regiment it appears in full as Joseph.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 19 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

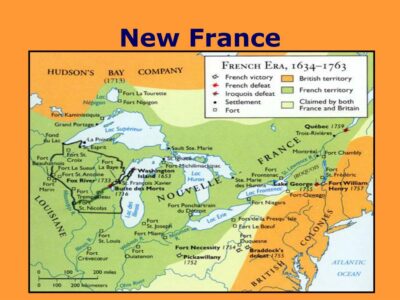

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.