The English batteries on the land side were pushing their work of destruction with relentless industry. Walls and bastions crumbled under their fire.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 20.

Another tribulation fell upon the general. Shirley had enjoined it upon him to keep in perfect harmony with the naval commander, and the injunction was in accord with Pepperrell’s conciliating temper. Warren was no less earnest than he for the success of the enterprise, lent him ammunition in time of need, and offered every aid in his power, while Pepperrell in letters to Shirley and Newcastle praised his colleague without stint. But in habits and character the two men differed widely. Warren was in the prime of life, and the ardor of youth still burned in him. He was impatient at the slow movement of the siege. Prisoners told him of a squadron expected from Brest, of which the “Vigilant” was the forerunner; and he feared that even if it could not defeat him, it might elude the blockade, and with the help of the continual fogs, get into Louisbourg in spite of him, thus making its capture impossible. Therefore, he called a council of his captains on board his flagship, the “Superbe,” and proposed a plan for taking the place without further delay. On the same day he laid it before Pepperrell. It was to the effect that all the King’s ships and provincial cruisers should enter the harbor, after taking on board sixteen hundred of Pepperrell’s men, and attack the town from the water side, while what was left of the army should assault it by land.[1] To accept the proposal would have been to pass over the command to Warren, only about twenty-one hundred of the New England men being fit for service at the time, while of these the general informs Warren that “six hundred are gone in quest of two bodies of French and Indians, who, we are informed, are gathering, one to the eastward, and the other to the westward.”[2]

Another tribulation fell upon the general. Shirley had enjoined it upon him to keep in perfect harmony with the naval commander, and the injunction was in accord with Pepperrell’s conciliating temper. Warren was no less earnest than he for the success of the enterprise, lent him ammunition in time of need, and offered every aid in his power, while Pepperrell in letters to Shirley and Newcastle praised his colleague without stint. But in habits and character the two men differed widely. Warren was in the prime of life, and the ardor of youth still burned in him. He was impatient at the slow movement of the siege. Prisoners told him of a squadron expected from Brest, of which the “Vigilant” was the forerunner; and he feared that even if it could not defeat him, it might elude the blockade, and with the help of the continual fogs, get into Louisbourg in spite of him, thus making its capture impossible. Therefore, he called a council of his captains on board his flagship, the “Superbe,” and proposed a plan for taking the place without further delay. On the same day he laid it before Pepperrell. It was to the effect that all the King’s ships and provincial cruisers should enter the harbor, after taking on board sixteen hundred of Pepperrell’s men, and attack the town from the water side, while what was left of the army should assault it by land.[1] To accept the proposal would have been to pass over the command to Warren, only about twenty-one hundred of the New England men being fit for service at the time, while of these the general informs Warren that “six hundred are gone in quest of two bodies of French and Indians, who, we are informed, are gathering, one to the eastward, and the other to the westward.”[2]

[1: Report of a Consultation of Officers on board his Majesty’s ship “Superbe,” enclosed in a letter of Warren to Pepperrell, 24 May, 1745.]

[2: Pepperrell to Warren, 28 May, 1745.]

To this Warren replies, with some appearance of pique, “I am very sorry that no one plan of mine, though approved by all my captains, has been so fortunate as to meet your approbation or have any weight with you.” And to show his title to consideration, he gives an extract from a letter written to him by Shirley, in which that inveterate flatterer hints his regret that, by reason of other employments, Warren could not take command of the whole expedition, — “which I doubt not,” says the governor, “would be a most happy event for his Majesty’s service.”

[Warren to Pepperrell, 29 May, 1745.]

Pepperrell kept his temper under this thrust and wrote to the commodore with invincible courtesy: “Am extremely sorry the fogs prevent me from the pleasure of waiting on you on board your ship,” adding that six hundred men should be furnished from the army and the transports to man the “Vigilant,” which was now the most powerful ship in the squadron. In short, he showed every disposition to meet Warren halfway. But the commodore was beginning to feel some doubts as to the expediency of the bold action he had proposed, and informed Pepperrell that his pilots thought it impossible to go into the harbor until the Island Battery was silenced. In fact, there was danger that if the ships got in while that battery was still alive and active, they would never get out again, but be kept there as in a trap, under the fire from the town ramparts.

Gridley’s artillery at Lighthouse Point had been doing its best, dropping bombshells with such precision into the Island Battery that the French soldiers were sometimes seen running into the sea to escape the explosions. Many of the Island guns were dismounted, and the place was fast becoming untenable. At the same time the English batteries on the land side were pushing their work of destruction with relentless industry, and walls and bastions crumbled under their fire. The French labored with energy under cover of night to repair the mischief; closed the shattered West Gate with a wall of stone and earth twenty feet thick, made an epaulement to protect what was left of the formidable Circular Battery, — all but three of whose sixteen guns had been dismounted, — stopped the throat of the Dauphin’s Bastion with a barricade of stone, and built a cavalier, or raised battery, on the King’s Bastion, — where, however, the English fire soon ruined it. Against that near and peculiarly dangerous neighbor, the advanced battery, or, as they called it, the Batterie de Francœur, they planted three heavy cannon to take it in flank. “These,” says Duchambon, “produced a marvelous effect, dismounted one of the cannon of the Bastonnais, and damaged all their embrasures, — which,” concludes the governor, “did not prevent them from keeping up a constant fire; and they repaired by night the mischief we did them by day.”

[Duchambon au Ministre, 2 Septembre, 1745.]

Pepperrell and Warren at length came to an understanding as to a joint attack by land and water. The Island Battery was by this time crippled, and the town batteries that commanded the interior of the harbor were nearly destroyed. It was agreed that Warren, whose squadron was now increased by recent arrivals to eleven ships, besides the provincial cruisers, should enter the harbor with the first fair wind, cannonade the town and attack it in boats, while Pepperrell stormed it from the land side. Warren was to hoist a Dutch flag under his pennant, at his main-top-gallant mast-head, as a signal that he was about to sail in; and Pepperrell was to answer by three columns of smoke, marching at the same time towards the walls with drums beating and colors flying.

[Warren to Pepperrell, 11 June, 1745. Pepperrell to Warren, 13 June, 1745.]

The French saw with dismay a large quantity of fascines carried to the foot of the glacis, ready

to fill the ditch, and their scouts came in with reports that more than a thousand scaling-ladders were lying behind the ridge of the nearest hill. Toil, loss of sleep, and the stifling air of the casemates, in which they were forced to take refuge, had sapped the strength of the besieged. The town was a ruin; only one house was untouched by shot or shell. “We could have borne all this,” writes the intendant Bigot; “but the scarcity of powder, the loss of the ‘Vigilant,’ the presence of the squadron, and the absence of any news from Marin, who had been ordered to join us with his Canadians and Indians, spread terror among troops and inhabitants. The townspeople said that they did not want to be put to the sword, and were not strong enough to resist a general assault.”[3] On the fifteenth of June they brought a petition to Duchambon, begging him to capitulate.[4]

[3: Bigot au Ministre, 1 Août, 1745.]

[4: Duchambon au Ministre, 2 Septembre, 1745.]

On that day Captain Sherburn, at the advanced battery, wrote in his diary: “By 12 o’clock we had got all our platforms laid, embrazures mended, guns in order, shot in place, cartridges ready, dined, gunners quartered, matches lighted to return their last favors, when we heard their drums beat a parley; and soon appeared a flag of truce, which I received midway between our battery and their walls, conducted the officer to Green Hill, and delivered him to Colonel Richman [Richmond].”

La Perelle, the French officer, delivered a note from Duchambon, directed to both Pepperrell and Warren, and asking for a suspension of arms to enable him to draw up proposals for capitulation.[5] Warren chanced to be on shore when the note came; and the two commanders answered jointly that it had come in good time, as they had just resolved on a general attack, and that they would give the governor till eight o’clock of the next morning to make his proposals.[6]

[5: Duchambon à Pepperrell et Warren, 26 Juin (new style), 1745.]

[6: Warren and Pepperrell to Duchambon, 15 June, 1745.]

They came in due time but were of such a nature that Pepperrell refused to listen to them, and sent back Bonaventure, the officer who brought them, with counter-proposals. These were the terms which Duchambon had rejected on the seventh of May, with added conditions; as, among others, that no officer, soldier, or inhabitant of Louisbourg should bear arms against the King of England or any of his allies for the space of a year. Duchambon stipulated, as the condition of his acceptance, that his troops should march out of the fortress with their arms and colors.[7] To this both the English commanders consented, Warren observing to Pepperrell “the uncertainty of our affairs, that depend so much on wind and weather, makes it necessary not to stickle at trifles.”[8] The articles were signed on both sides, and on the seventeenth the ships sailed peacefully into the harbor, while Pepperrell with a part of his ragged army entered the south gate of the town. “Never was a place more mal’d [mauled] with cannon and shells,” he writes to Shirley; “neither have I red in History of any troops behaving with greater courage. We gave them about nine thousand cannon-balls and six hundred bombs.”[9] Thus this unique military performance ended in complete and astonishing success.

[7: Duchambon à Warren et Pepperrell, 27 Juin (new style), 1745.]

[8: Pepperrell to Warren, 16 June, 1745. Warren to Pepperrell, 16 June, 1745.]

[9: Pepperrell to Shirley, 18 June (old style), 1745. Ibid., 4 July, 1745.]

According to English accounts, the French had lost about three hundred men during the siege; but their real loss seems to have been not much above a third of that number. On the side of the besiegers, the deaths from all causes were only a hundred and thirty, about thirty of which were from disease. The French used their muskets to good purpose; but their mortar practice was bad, and close as was the advanced battery to their walls, they often failed to hit it, while the ground on both sides of it looked like a ploughed field, from the bursting of their shells. Their surrender was largely determined by want of ammunition, as, according to one account, the French had but thirty-seven barrels of gunpowder left,[10] — in which particular the besiegers fared little better.[11]

[10: Habitant de Louisbourg.]

[11: Pepperrell more than once complains of a total want of both powder and balls. Warren writes to him on May 29: “It is very lucky that we could spare you some powder; I am told you had not a grain left.”]

The New England men had been full of confidence in the result of the proposed assault, and a French writer says that the timely capitulation saved Louisbourg from a terrible catastrophe;[12] yet, ill-armed and disorderly as the besiegers were, it may be doubted whether the quiet ending of the siege was not as fortunate for them as for their foes. The discouragement of the French was increased by greatly exaggerated ideas of the force of the “Bastonnais.” The Habitant de Louisbourg places the land-force alone at eight or nine thousand men, and Duchambon reports to the minister D’Argenson that he was attacked in all by thirteen thousand. His mortifying position was a sharp temptation to exaggerate; but his conduct can only be explained by a belief that the force of his enemy was far greater than it was in fact.

[12: “C’est par une protection visible de la Providence que nous avons prévenu une journée qui nous auroit été si funeste.” — Lettre d’un Habitant de Louisbourg.]

Warren thought that the proposed assault would succeed and wrote to Pepperrell that he hoped they would “soon keep a good house together, and give the Ladys of Louisbourg a Gallant Ball.”[13] During his visit to the camp on the day when the flag of truce came out, he made a speech to the New England soldiers, exhorting them to behave like true Englishmen; at which they cheered lustily. Making a visit to the Grand Battery on the same day, he won high favor with the regiment stationed there by the gift of a hogshead of rum to drink his health.

[13: Warren to Pepperrell, 10 June, 1745.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 20 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

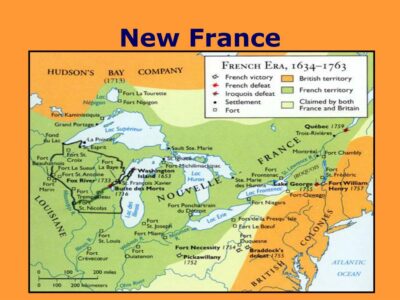

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.