The French were so confident in the strength of their fortifications that they boasted that women alone could defend them.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 19.

The cannon could be loaded only under a constant fire of musketry, which the enemy briskly returned. The French practice was excellent. A soldier who in bravado mounted the rampart and stood there for a moment was shot dead with five bullets. The men on both sides called to each other in scraps of bad French or broken English; while the French drank ironical healths to the New England men and gave them bantering invitations to breakfast.

The cannon could be loaded only under a constant fire of musketry, which the enemy briskly returned. The French practice was excellent. A soldier who in bravado mounted the rampart and stood there for a moment was shot dead with five bullets. The men on both sides called to each other in scraps of bad French or broken English; while the French drank ironical healths to the New England men and gave them bantering invitations to breakfast.

Sherburn continues his diary. “Sunday morning. Began our fire with as much fury as possible, and the French returned it as warmly from the Citidale [citadel], West Gate, and North East Battery with Cannon, Mortars, and continual showers of musket balls; but by 11 o’clock we had beat them all from their guns.” He goes on to say that at noon his men were forced to stop firing from want of powder, that he went with his gunners to get some, and that while they were gone, somebody, said to be Mr. Vaughan, brought a supply, on which the men loaded the forty-two pounders in a bungling way, and fired them. One was dismounted, and the other burst; a barrel and a half-barrel of powder blew up, killed two men, and injured two more. Again: “Wednesday. Hot fire on both sides, till the French were beat from all their guns. May 29th went to 2 Gun [Titcomb’s] Battery to give the gunners some directions; then returned to my own station, where I spent the rest of the day with pleasure, seeing our Shott Tumble down their walls and Flagg Staff.”

The following is the intendant Bigot’s account of the effect of the New England fire: “The enemy established their batteries to such effect that they soon destroyed the greater part of the town, broke the right flank of the King’s Bastion, ruined the Dauphin Battery with its spur, and made a breach at the Porte Dauphine [West Gate], the neighboring wall, and the sort of redan adjacent.”[1] Duchambon says in addition that the cannon of the right flank of the King’s Bastion could not be served, by reason of the continual fire of the enemy, which broke the embrasures to pieces; that when he had them repaired, they were broken to pieces (démantibulés) again, — and nobody could keep his ground behind the wall of the quay, which was shot through and through and completely riddled.[2] The town was ploughed with cannon-balls, the streets were raked from end to end, nearly all the houses damaged, and the people driven for refuge into the stifling casemates. The results were creditable to novices in gunnery.

[1: Bigot au Ministre, 1 Août, 1745.]

[2: Duchambon au Ministre, 2 Septembre, 1745.]

The repeated accidents from the bursting of cannon were no doubt largely due to unskillful loading and the practice of double-shotting, to which the over-zealous artillerists are said to have often resorted.

[“Another forty-two pound gun burst at the Grand Battery. All the guns are in danger of going the same way, by double-shotting them, unless under better regulation than at present.” — Waldo to Pepperrell, 20 May, 1745.

Waldo had written four days before: “Captain Hale, of my regiment, is dangerously hurt by the bursting of another gun. He was our mainstay for gunnery since Captain Rhodes’s misfortune” (also caused by the bursting of a cannon). Waldo to Pepperrell, 16 May, 1745.]

It is said, in proof of the orderly conduct of the men, that not one of them was punished during all the siege; but this shows the mild and conciliating character of the general quite as much as any peculiar merit of the soldiers. The state of things in and about the camp was compared by the caustic Dr. Douglas to “a Cambridge Commencement,” which academic festival was then attended by much rough frolic and boisterous horseplay among the disorderly crowds, white and black, bond and free, who swarmed among the booths on Cambridge Common. The careful and scrupulous Belknap, who knew many who took part in the siege, says: “Those who were on the spot have frequently, in my hearing, laughed at the recital of their own irregularities, and expressed their admiration when they reflected on the almost miraculous preservation of the army from destruction.” While the cannon bellowed in the front, frolic and confusion reigned at the camp, where the men raced, wrestled, pitched quoits, fired at marks, — though there was no ammunition to spare, — and ran after the French cannonballs, which were carried to the batteries, to be returned to those who sent them. Nor were calmer recreations wanting. “Some of our men went a fishing, about 2 miles off,” writes Lieutenant Benjamin Cleaves in his diary: “caught 6 Troutts.” And, on the same day, “Our men went to catch Lobsters: caught 30.” In view of this truant disposition, it is not surprising that the besiegers now and 113 then lost their scalps at the hands of prowling Indians who infested the neighborhood. Yet through all these gambols ran an undertow of enthusiasm, born in brains still fevered from the “Great Awakening.” The New England soldier, a growth of sectarian hotbeds, fancied that he was doing the work of God. The army was Israel, and the French were Canaanitish idolaters. Red-hot Calvinism, acting through generations, had modified the transplanted Englishman; and the descendant of the Puritans was never so well pleased as when teaching their duty to other people, whether by pen, voice, or bombshells. The ragged artillerymen, battering the walls of papistical Louisbourg, flattered themselves with the notion that they were champions of gospel truth.

Barefoot and tattered, they toiled on with indomitable pluck and cheerfulness, doing the work which oxen could not do, with no comfort but their daily dram of New England rum, as they plodded through the marsh and over rocks, dragging the ponderous guns through fog and darkness. Their spirit could not save them from the effects of excessive fatigue and exposure.

They were ravaged with diarrhea and fever, till fifteen hundred men were at one time on the sick-list, and at another, Pepperrell reported that of the four thousand only about twenty-one hundred were fit for duty.[3] Nearly all at last recovered, for the weather was unusually good; yet the number fit for service was absurdly small. Pepperrell begged for reinforcements but got none till the siege was ended.

[3: Pepperrell to Warren, 28 May, 1745.]

It was not his nature to rule with a stiff hand, — and this, perhaps, was fortunate. Order and discipline, the sinews of an army, were out of the question; and it remained to do as well as might be without them, keep men and officers in good-humor, and avoid all that could dash their ardor. For this, at least, the merchant-general was well fitted. His popularity had helped to raise the army, and perhaps it helped now to make it efficient. His position was no bed of roses. Worries, small and great, pursued him without end. He made friends of his officers, kept a bountiful table at his tent, and labored to soothe their disputes and jealousies, and satisfy their complaints. So generous were his contributions to the common cause that according to a British officer who speaks highly of his services, he gave to it, in one form or another, £10,000 out of his own pocket.

[Letter from an Officer of Marines appended to A particular Account of the Taking of Cape Breton (London, 1745).]

His letter-books reveal a swarm of petty annoyances, which may have tried his strength and patience as much as more serious cares. The soldiers complained that they were left without clothing, shoes, or rum; and when he implored the Committee of War to send them, Osborne, the chairman, replied with explanations why it could not be done. Letters came from wives and fathers entreating that husbands and sons who had gone to the war should be sent back. At the end of the siege a captain “humble begs leave for to go home,” because he lives in a very dangerous country, and his wife and children are “in a declining way” without him. Then two entire companies raised on the frontier offered the same petition on similar grounds. Sometimes Pepperrell was beset with prayers for favors and promotion; sometimes with complaints from one corps or another that an undue share of work had been imposed on it. One Morris, of Cambridge, writes a moving petition that his slave “Cuffee,” who had joined the army, should be restored to him, his lawful master. One John Alford sends the general a number of copies of the Rev. Mr. Prentice’s late sermon, for distribution, assuring him that “it will please your whole army of volunteers, as he has shown them the way to gain by their gallantry the hearts and affections of the Ladys.” The end of the siege brought countless letters of congratulation, which, whether lay or clerical, never failed to remind him, in set phrases, that he was but an instrument in the hands of Providence.

One of his most persistent correspondents was his son-in-law, Nathaniel Sparhawk, a thrifty merchant, with a constant eye to business, who generally began his long-winded epistles with a bulletin concerning the health of “Mother Pepperrell,” and rarely ended them without charging his father-in-law with some commission, such as buying for him the cargo of a French prize, if he could get it cheap. Or thus: “If you would procure for me a hogshead of the best Clarett, and a hogshead of the best white wine, at a reasonable rate, it would be very grateful to me.” After pestering him with a few other commissions, he tells him that “Andrew and Bettsy [children of Pepperrell] send their proper compliments,” and signs himself, with the starched flourish of provincial breeding, “With all possible Respect, Honoured Sir, Your Obedient Son and Servant.”[4] Pepperrell was much annoyed by the conduct of the masters of the transports, of whom he wrote: “The unaccountable irregular behaviour of these fellows is the greatest fatigue I meet with;” but it may be doubted whether his son-in-law did not prove an equally efficient persecutor.

[4: Sparhawk to Pepperrell, — June, 1745. This is but one of many letters from Sparhawk.]

Frequent councils of war were held in solemn form at headquarters. On the seventh of May a summons to surrender was sent to Duchambon, who replied that he would answer with his cannon. Two days after, we find in the record of the council the following startling entry: “Advised unanimously that the Town of Louisbourg be attacked by storm this Night.” Vaughan was a member of the board, and perhaps his impetuous rashness had turned the heads of his colleagues. To storm the fortress at that time would have been a desperate attempt for the best-trained and best-led troops. There was as yet no breach in the walls, nor the beginning of one; and the French were so confident in the strength of their fortifications that they boasted that women alone could defend them. Nine in ten of the men had no bayonets,[5] many had no shoes, and it is said that the scaling-ladders they had brought from Boston were ten feet too short.[6] Perhaps it was unfortunate for the French that the army was more prudent than its leaders; and another council being called on the same day, it was “Advised, That, inasmuch as there appears a great Dissatisfaction in many of the officers and Soldiers at the designed attack of the Town by Storm this Night, the said Attack be deferred for the present.”[7]

[5: Shirley to Newcastle, 7 June, 1745.]

[6: Douglas, Summary, i. 347.]

[7: Record of the Council of War, 9 May, 1745.]

Another plan was adopted, hardly less critical, though it found favor with the army. This was the assault of the Island Battery, which closed the entrance of the harbor to the British squadron, and kept it open to ships from France. Nobody knew precisely how to find the two landing-places of this formidable work, which were narrow gaps between rocks lashed with almost constant surf; but Vaughan would see no difficulties, and wrote to Pepperrell that if he would give him the command and leave him to manage the attack in his own way, he would engage to send the French flag to headquarters within forty-eight hours.[8] On the next day he seems to have thought the command assured to him, and writes from the Grand Battery that the carpenters are at work mending whale-boats and making paddles, asking at the same time for plenty of pistols and one hundred hand-grenades, with men who know how to use them.[9] The weather proved bad, and the attempt was deferred. This happened several times, till Warren grew impatient, and offered to support the attack with two hundred sailors.

[8: Vaughan to Pepperrell, 11 May, 1745.]

[9: Vaughan to Pepperrell, 12 May, 1745.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 20 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

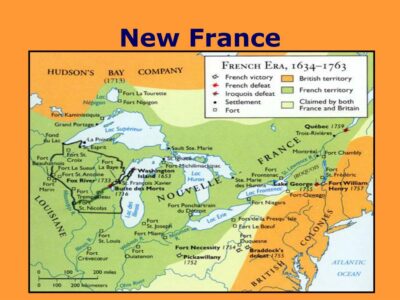

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.