The French, much encouraged by their late success, were plunged again into despondency by a disaster which had happened a week before the affair of the Island Battery.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 20.

At length, on the twenty-third, the volunteers for the perilous enterprise mustered at the Grand Battery, whence the boats were to set out. Brigadier Waldo, who still commanded there, saw them with concern and anxiety, as they came dropping in, in small squads, without officers, noisy, disorderly, and, in some cases, more or less drunk. “I doubt,” he told the general, “whether straggling fellows, three, four, or seven out of a company, ought to go on such a service.”[1] A bright moon and northern lights again put off the attack. The volunteers remained at the Grand Battery, waiting for better luck. “They seem to be impatient for action,” writes Waldo. “If there were a more regular appearance, it would give me greater sattysfaction.”[2] On the twenty-sixth their wish for action was fully gratified. The night was still and dark, and the boats put out from the battery towards twelve o’clock, with about three hundred men on board.[3] These were to be joined by a hundred or a hundred and fifty more from Gorham’s regiment, then stationed at Lighthouse Point. The commander was not Vaughan, but one Brooks, — the choice of the men themselves, as were also his subordinates.[4] They moved slowly, the boats being propelled, not by oars, but by paddles, which, if skillfully used, would make no noise. The wind presently rose; and when they found a landing-place, the surf was lashing the rocks with even more than usual fury. There was room for but three boats at once between the breakers on each hand. They pushed in, and the men scrambled ashore with what speed they might.

At length, on the twenty-third, the volunteers for the perilous enterprise mustered at the Grand Battery, whence the boats were to set out. Brigadier Waldo, who still commanded there, saw them with concern and anxiety, as they came dropping in, in small squads, without officers, noisy, disorderly, and, in some cases, more or less drunk. “I doubt,” he told the general, “whether straggling fellows, three, four, or seven out of a company, ought to go on such a service.”[1] A bright moon and northern lights again put off the attack. The volunteers remained at the Grand Battery, waiting for better luck. “They seem to be impatient for action,” writes Waldo. “If there were a more regular appearance, it would give me greater sattysfaction.”[2] On the twenty-sixth their wish for action was fully gratified. The night was still and dark, and the boats put out from the battery towards twelve o’clock, with about three hundred men on board.[3] These were to be joined by a hundred or a hundred and fifty more from Gorham’s regiment, then stationed at Lighthouse Point. The commander was not Vaughan, but one Brooks, — the choice of the men themselves, as were also his subordinates.[4] They moved slowly, the boats being propelled, not by oars, but by paddles, which, if skillfully used, would make no noise. The wind presently rose; and when they found a landing-place, the surf was lashing the rocks with even more than usual fury. There was room for but three boats at once between the breakers on each hand. They pushed in, and the men scrambled ashore with what speed they might.

[1: Waldo to Pepperrell, 23 May, 1745.]

[2: Ibid., 26 May, 1745.]

[3: “There is scarce three hundred men on this atact [attack], so there will be a sufficient number of Whail boats.” — Waldo to Pepperrell, 26 May, 10½ p. m.]

[4: The list of a company of forty-two “subscribers to go voluntarily upon an attack against the Island Battery” is preserved. It includes a negro called “Ruben.” The captain, chosen by the men, was Daniel Bacon. The fact that neither this name nor that of Brooks, the chief commander, is to be found in the list of commissioned officers of Pepperrell’s little army (see Parsons, Life of Pepperrell, Appendix) suggests the conclusion that the “subscribers” were permitted to choose officers from their own ranks. This list, however, is not quite complete.]

The Island Battery was a strong work, walled in on all sides, garrisoned by a hundred and eighty men, and armed with thirty cannon, seven swivels, and two mortars.[5] It was now a little after midnight. Captain d’Aillebout, the commandant, was on the watch, pacing the battery platform; but he seems to have seen nothing unusual till about a hundred and fifty men had got on shore, when they had the folly to announce their presence by three cheers. Then, in the words of General Wolcott, the battery “blazed with cannon, swivels, and small arms.” The crowd of boats, dimly visible through the darkness, as they lay just off the landing, waiting their turn to go in, were at once the target for volleys of grapeshot, langrage-shot, and musket-balls, of which the men on shore had also their share. These succeeded, however, in planting twelve scaling-ladders against the wall.[6] It is said that some of them climbed into the place, and the improbable story is told that Brooks, their commander, was hauling down the French flag when a Swiss grenadier cut him down with a cutlass.[7] Many of the boats were shattered or sunk, while those in the rear, seeing the state of things, appear to have sheered off. The affair was soon reduced to an exchange of shots between the garrison and the men who had landed, and who, standing on the open ground without the walls, were not wholly invisible, while the French, behind their ramparts, were completely hidden. “The fire of the English,” says Bigot, “was extremely obstinate, but without effect, as they could not see to take aim.” They kept it up till daybreak, or about two hours and a half; and then, seeing themselves at the mercy of the French, surrendered to the number of one hundred and nineteen, including the wounded, three or more of whom died almost immediately. By the most trustworthy accounts the English loss in killed, drowned, and captured was one hundred and eighty-nine; or, in the words of Pepperrell, “nearly half our party.”[8] Disorder, precipitation, and weak leadership ruined what hopes the attempt ever had.

[5: Journal of the Siege, appended to Shirley’s report.]

[6: Duchambon au Ministre, 2 Septembre, 1745. Bigot au Ministre, 1 Août, 1745.]

[7: The exploit of the boy William Tufts in climbing the French flagstaff and hanging his red coat at the top as a substitute for the British flag, has also been said to have taken place on this occasion. It was, as before mentioned, at the Grand Battery.]

[8: Douglas makes it a little less. “We lost in this mad frolic sixty men killed and drowned, and one hundred and sixteen prisoners.” — Summary, i. 353.]

As this was the only French success during the siege, Duchambon makes the most of it. He reports that the battery was attacked by a thousand men, supported by eight hundred more, who were afraid to show themselves; and, farther, that there were thirty-five boats, all of which were destroyed or sunk,[9] — though he afterwards says that two of them got away with thirty men, being all that were left of the thousand. Bigot, more moderate, puts the number of assailants at five hundred, of whom he says that all perished, except the one hundred and nineteen who were captured.[10]

[9: “Toutes les barques furent brisées ou coulées à fond; le feu fut continuel depuis environ minuit jusqu’à trois heures du matin.” — Duchambon au Ministre, 2 Septembre, 1745.]

[10: Bigot au Ministre, 1 Août, 1745.]

At daybreak Louisbourg rang with shouts of triumph. It was plain that a disorderly militia

could not capture the Island Battery. Yet captured or silenced it must be; and orders were given to plant a battery against it at Lighthouse Point, on the eastern side of the harbor’s mouth, at the distance of a short half-mile. The neighboring shore was rocky and almost inaccessible. Cannon and mortars were carried in boats to the nearest landing-place, hauled up a steep cliff, and dragged a mile and a quarter to the chosen spot, where they were planted under the orders of Colonel Gridley, who thirty years after directed the earthworks on Bunker Hill. The new battery soon opened fire with deadly effect.

The French, much encouraged by their late success, were plunged again into despondency by a disaster which had happened a week before the affair of the Island Battery but did not come to their knowledge till some time after. On the nineteenth of May a fierce cannonade was heard from the harbor, and a large French ship-of-war was seen hotly engaged with several vessels of the squadron. She was the “Vigilant,” carrying 64 guns and 560 men, and commanded by the Marquis de la Maisonfort. She had come from France with munitions and stores, when on approaching Louisbourg she met one of the English cruisers, — some say the “Mermaid,” of 40 guns, and others the “Shirley,” of 20. Being no match for her, the British or provincial frigate kept up a running fight and led her towards the English fleet. The “Vigilant” soon found herself beset by several other vessels, and after a gallant resistance and the loss of eighty men, struck her colors. Nothing could be more timely for the New England army, whose ammunition and provisions had sunk perilously low. The French prize now supplied their needs and drew from the Habitant de Louisbourg; the mournful comment, “We were victims devoted to appease the wrath of Heaven, which turned our own arms into weapons for our enemies.”

Nor was this the last time when the defenders of Louisbourg supplied the instruments of their own destruction; for ten cannon were presently unearthed at low tide from the flats near the careening wharf in the northeast arm of the harbor, where they had been hidden by the French some time before. Most of them proved sound; and being mounted at Lighthouse Point, they were turned against their late owners at the Island Battery.

When Gorham’s regiment first took post at Lighthouse Point, Duchambon thought the movement so threatening that he forgot his former doubts, and ordered a sortie against it, under the Sieur de Beaubassin. Beaubassin landed, with a hundred men, at a place called Lorembec, and advanced to surprise the English detachment; but was discovered by an outpost of forty men, who attacked and routed his party.[11] Being then joined by eighty Indians, Beaubassin had several other skirmishes with English scouting-parties, till, pushed by superior numbers, and their leader severely wounded, his men regained Louisbourg by sea, escaping with difficulty from the guard-boats of the squadron. The Sieur de la Vallière, with a considerable party of men, tried to burn Pepperrell’s storehouses, near Flat Point Cove; but ten or twelve of his followers were captured, and nearly all the rest wounded. Various other petty encounters took place between English scouting-parties and roving bands of French and Indians, always ending, according to Pepperrell, in the discomfiture of the latter. To this, however, there was at least one exception. Twenty English were waylaid and surrounded near Petit Lorembec by forty or fifty Indians, accompanied by two or three Frenchmen. Most of the English were shot down, several escaped, and the rest surrendered on promise of life; upon which the Indians, in cold blood, shot or speared some of them, and atrociously tortured others.

[11: Journal of the Siege, appended to Shirley’s report. Pomeroy, Journal]

This suggested to Warren a device which had two objects, — to prevent such outrages in future, and to make known to the French that the ship “Vigilant,” the mainstay of their hopes, was in English hands. The treatment of the captives was told to the Marquis de la Maisonfort, late captain of the “Vigilant,” now a prisoner on board the ship he had commanded, and he was requested to lay the facts before Duchambon. This he did with great readiness, in a letter containing these words: “It is well that you should be informed that the captains and officers of this squadron treat us, not as their prisoners, but as their good friends, and take particular pains that my officers and crew should want for nothing; therefore it seems to me just to treat them in like manner, and to punish those who do otherwise and offer any insult to the prisoners who may fall into your hands.”

Captain M’Donald, of the marines, carried this letter to Duchambon under a flag-of-truce. Though familiar with the French language, he spoke to the governor through an interpreter, so that the French officers present, who hitherto had only known that a large ship had been taken, expressed to each other without reserve their discouragement and dismay when they learned that the prize was no other than the “Vigilant.” Duchambon replied to La Maisonfort’s letter that the Indians alone were answerable for the cruelties in question, and that he would forbid such conduct for the future.

[De la Maisonfort à Duchambon, 18 Juin (new style), 1745. Duchambon à De la Maisonfort, 19 Juin (new style), 1745.]

The besiegers were now threatened by a new danger. We have seen that in the last summer the Sieur Duvivier had attacked Annapolis. Undaunted by ill-luck, he had gone to France to beg for help to attack it again; two thousand men were promised him, and in anticipation of their arrival the governor of Canada sent a body of French and Indians, under the noted partisan Marin, to meet and co-operate with them. Marin was ordered to wait at Les Mines till he heard of the arrival of the troops from France; but he grew impatient and resolved to attack Annapolis without them. Accordingly, he laid siege to it with the six or seven hundred whites and Indians of his party, aided by the so-called Acadian neutrals. Mascarene, the governor, kept them at bay till the twenty-fourth of May, when, to his surprise, they all disappeared. Duchambon had sent them an order to make all haste to the aid of Louisbourg. As the report of this reached the besiegers, multiplying Marin’s force fourfold, they expected to be attacked by numbers more than equal to those of their own effective men. This wrought a wholesome reform. Order was established in the camp, which was now fenced with palisades and watched by sentinels and scouting-parties.

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 20 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

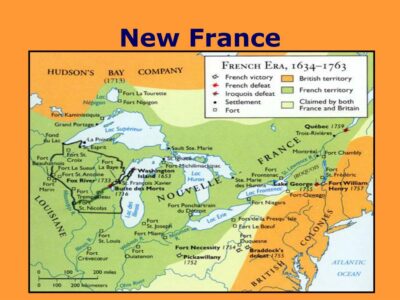

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.