Few knew well what a fortress was, and nobody knew how to attack one.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 18.

The die was cast, and now doubt and hesitation vanished. All alike set themselves to push on the work. Shirley wrote to all the colonies, as far south as Pennsylvania, to ask for co-operation. All excused themselves except Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island, and the whole burden fell on the four New England colonies. These, and Massachusetts above all, blazed with pious zeal; for as the enterprise was directed against Roman Catholics, it was supposed in a peculiar manner to commend itself to Heaven. There were prayers without ceasing in churches and families, and all was ardor, energy, and confidence; while the other colonies looked on with distrust, dashed with derision. When Benjamin Franklin, in Philadelphia, heard what was afoot, he wrote to his brother in Boston, “Fortified towns are hard nuts to crack, and your teeth are not accustomed to it; but some seem to think that forts are as easy taken as snuff.”[1] It has been said of Franklin that while he represented some of the New England qualities, he had no part in that enthusiasm of which our own time saw a crowning example when the cannon opened at Fort Sumter, and which pushes to its end without reckoning chances, counting costs, or heeding the scoffs of ill-wishers.

The die was cast, and now doubt and hesitation vanished. All alike set themselves to push on the work. Shirley wrote to all the colonies, as far south as Pennsylvania, to ask for co-operation. All excused themselves except Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island, and the whole burden fell on the four New England colonies. These, and Massachusetts above all, blazed with pious zeal; for as the enterprise was directed against Roman Catholics, it was supposed in a peculiar manner to commend itself to Heaven. There were prayers without ceasing in churches and families, and all was ardor, energy, and confidence; while the other colonies looked on with distrust, dashed with derision. When Benjamin Franklin, in Philadelphia, heard what was afoot, he wrote to his brother in Boston, “Fortified towns are hard nuts to crack, and your teeth are not accustomed to it; but some seem to think that forts are as easy taken as snuff.”[1] It has been said of Franklin that while he represented some of the New England qualities, he had no part in that enthusiasm of which our own time saw a crowning example when the cannon opened at Fort Sumter, and which pushes to its end without reckoning chances, counting costs, or heeding the scoffs of ill-wishers.

[1: Sparks, Works of Franklin, vii. 16.]

The prevailing hope and faith were, it is true, born largely of ignorance, aided by the contagious zeal of those who first broached the project; for as usual in such cases, a few individuals supplied the initiate force of the enterprise. Vaughan the indefatigable rode express to Portsmouth with a letter from Shirley to Benning Wentworth, governor of New Hampshire. That pompous and self-important personage admired the Massachusetts governor, who far surpassed him in talents and acquirements, and who at the same time knew how to soothe his vanity. Wentworth was ready to do his part, but his province had no money, and the King had ordered him to permit the issue of no more paper currency. The same prohibition had been laid upon Shirley; but he, with sagacious forecast, had persuaded his masters to relent so far as to permit the issue of £50,000 in what were called bills of credit to meet any pressing exigency of war. He told this to Wentworth, and succeeded in convincing him that his province might stretch her credit like Massachusetts, in case of similar military need. New Hampshire was thus enabled to raise a regiment of five hundred men out of her scanty population, with the condition that a hundred and fifty of them should be paid and fed by Massachusetts.

[Correspondence of Shirley and Wentworth, in Belknap Papers. Provincial Papers of New Hampshire, v.]

Shirley was less fortunate in Rhode Island. The governor of that little colony called Massachusetts “our avowed enemy, always trying to defame us.”[2] There was a grudge between the neighbors, due partly to notorious ill-treatment by the Massachusetts Puritans of Roger Williams, founder of Rhode Island, and partly to one of those boundary disputes which often produced ill-blood among the colonies. The representatives of Rhode Island, forgetting past differences, voted to raise a hundred and fifty men for the expedition, till, learning that the project was neither ordered nor approved by the Home Government, they prudently reconsidered their action. They voted, however, that the colony sloop “Tartar,” carrying fourteen cannon and twelve swivels, should be equipped and manned for the service, and that the governor should be instructed to find and commission a captain and a lieutenant to command her.[3]

[2: Governor Wanton to the Agent of Rhode Island,20 December, 1745, in Colony Records of Rhode Island, v.]

[3: Colony Records of Rhode Island, v. (February, 1745).]

Connecticut promised five hundred and sixteen men and officers, on condition that Roger Wolcott, their commander, should have the second rank in the expedition. Shirley accordingly commissioned him as major-general. As Massachusetts was to supply above three thousand men, or more than three quarters of the whole force, she had a natural right to name a commander-in-chief.

It was not easy to choose one. The colony had been at peace for twenty years, and except some grizzled Indian fighters of the last war, and some survivors of the Carthagena expedition, nobody had seen service. Few knew well what a fortress was, and nobody knew how to attack one. Courage, energy, good sense, and popularity were the best qualities to be hoped for in the leader. Popularity was indispensable, for the soldiers were all to be volunteers, and they would not enlist under a commander whom they did not like. Shirley’s choice was William Pepperrell, a merchant of Kittery. Knowing that Benning Wentworth thought himself the man for the place, he made an effort to placate him, and wrote that he would gladly have given him the chief command but for his gouty legs. Wentworth took fire at the suggestion, forgot his gout, and declared himself ready to serve his country and assume the burden of command. The position was awkward, and Shirley was forced to reply, “On communicating your offer to two or three gentlemen in whose judgment I most confide, I found them clearly of opinion that any alteration of the present command would be attended with great risk, both with respect to our Assembly and the soldiers being entirely disgusted.”

[Shirley to Wentworth, 16 February, 1745.]

The painter Smibert has left us a portrait of Pepperrell, — a good bourgeois face, not without dignity, though with no suggestion of the soldier. His spacious house at Kittery Point still stands, sound and firm, though curtailed in some of its proportions. Not far distant is another noted relic of colonial times, the not less spacious mansion built by the disappointed Wentworth at Little Harbor. I write these lines at a window of this curious old house, and before me spreads the scene familiar to Pepperrell from childhood. Here the river Piscataqua widens to join the sea, holding in its gaping mouth the large island of Newcastle, with

attendant groups of islets and island rocks, battered with the rack of ages, studded with dwarf savins, or half clad with patches of whortleberry bushes, sumach, and the shining wax-myrtle, green in summer, red with the touch of October. The flood tide pours strong and full around them, only to ebb away and lay bare a desolation of rocks and stones buried in a shock of brown drenched seaweed, broad tracts of glistening mud, sand-banks black with mussel-beds, and half-submerged meadows of eel-grass, with myriads of minute shell-fish clinging to its long lank tresses. Beyond all these lies the main, or northern channel, more than deep enough, even when the tide is out, to float a line-of-battle-ship. On its farther bank stands the old house of the Pepperrells, wearing even now an air of dingy respectability. Looking through its small, quaint window-panes, one could see across the water the rude dwellings of fishermen along the shore of Newcastle, and the neglected earthwork called Fort William and Mary, that feebly guarded the river’s mouth. In front, the Piscataqua, curving southward, widened to meet the Atlantic between rocky headlands and foaming reefs, and in dim distance the Isles of Shoals seemed floating on the pale gray sea.

Behind the Pepperrell house was a garden, probably more useful than ornamental, and at the foot of it were the owner’s wharves, with storehouses for salt-fish, naval stores, and imported goods for the country trade.

Pepperrell was the son of a Welshman[4] who migrated in early life to the Isles of Shoals, and thence to Kittery, where, by trade, ship-building, and the fisheries, he made a fortune, most of which he left to his son William. The young Pepperrell learned what little was taught at the village school, supplemented by a private tutor, whose instructions, however, did not perfect him in English grammar. In the eyes of his self-made father, education was valuable only so far as it could make a successful trader; and on this point he had reason to be satisfied, as his son passed for many years as the chief merchant in New England. He dealt in ships, timber, naval stores, fish, and miscellaneous goods brought from England; and he also greatly prospered by successful land purchases, becoming owner of the greater part of the growing towns of Saco and Scarborough. When scarcely twenty-one, he was made justice of the peace, on which he ordered from London what his biographer calls a law library, consisting of a law dictionary, Danvers’ “Abridgment of the Common Law,” the “Complete Solicitor,” and several other books. In law as in war, his best qualities were good sense and goodwill. About the time when he was made a justice, he was commissioned captain of militia, then major, then lieutenant-colonel, and at last colonel, commanding all the militia of Maine. The town of Kittery chose him to represent her in the General Court, Maine being then a part of Massachusetts. Finally, he was made a member of the Governor’s Council, — a post which he held for thirty-two years, during eighteen of which he was president of the board.

[4: “A native of Ravistock Parish, in Wales.” Parsons, Life of Pepperrell. Mrs. Adelaide Cilley Waldron, a descendant of Pepperrell, assures me, however, that his father, the emigrant, came, not from Wales, but from Devonshire.]

These civil dignities served him as educators better than tutor or village school; for they brought him into close contact with the chief men of the province; and in the Massachusetts of that time, so different from our own, the best education and breeding were found in the official class. At once a provincial magnate and the great man of a small rustic village, his manners are said to have answered to both positions, — certainly they were such as to make him popular. But whatever he became as a man, he learned nothing to fit him to command an army and lay siege to Louisbourg. Perhaps he felt this, and thought, with the governor of Rhode Island, that “the attempt to reduce that prodigiously strong town was too much for New England, which had not one officer of experience, nor even an engineer.”[5] Moreover, he was unwilling to leave his wife, children, and business. He was of a religious turn of mind, and partial to the clergy, who, on their part, held him in high favor. One of them, the famous preacher, George Whitefield, was a guest at his house when he heard that Shirley had appointed him to command the expedition against Louisbourg. Whitefield had been the leading spirit in the recent religious fermentation called the Great Awakening, which, though it produced bitter quarrels among the ministers, besides other undesirable results, was imagined by many to make for righteousness. So thought the Rev. Thomas Prince, who mourned over the subsiding delirium of his flock as a sign of backsliding. “The heavenly shower was over,” he sadly exclaims; “from fighting the devil they must turn to fighting the French.” Pepperrell, always inclined to the clergy, and now in great perplexity and doubt, asked his guest Whitefield whether or not he had better accept the command. Whitefield gave him cold comfort, told him that the enterprise was not very promising, and that if he undertook it, he must do so “with a single eye,” prepared for obloquy if he failed, and envy if he succeeded.[6] Henry Sherburn, commissary of the New Hampshire regiment, begged Whitefield to furnish a motto for the flag. The preacher, who, zealot as he was, seemed unwilling to mix himself with so madcap a business, hesitated at first, but at length consented, and suggested the words, Nil desperandum Christo duce, which, being adopted, gave the enterprise the air of a crusade. It had, in fact, something of the character of one. The cause was imagined to be the cause of Heaven, crowned with celestial benediction. It had the fervent support of the ministers, not only by prayers and sermons, but, in one case, by counsels wholly temporal. A certain pastor, much esteemed for benevolence, proposed to Pepperrell, who had at last accepted the command, a plan, unknown to Vauban, for confounding the devices of the enemy. He advised that two trustworthy persons should cautiously walk together along the front of the French ramparts under cover of night, one of them carrying a mallet, with which he was to hammer the ground at short intervals. The French sentinels, it seems to have been supposed, on hearing this mysterious thumping, would be so bewildered as to give no alarm. While one of the two partners was thus employed, the other was to lay his ear to the ground, which, as the adviser thought, would return a hollow sound if the artful foe had dug a mine under it; and whenever such secret danger was detected, a mark was to be set on the spot, to warn off the soldiers.[7]

[5: Governor Wanton to the Agent of Rhode Island in London, 20 December, 1745.]

[6: Parsons, Life of Pepperrell, 51.]

[7: Belknap, Hist. New Hampshire, ii. 208.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 18 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

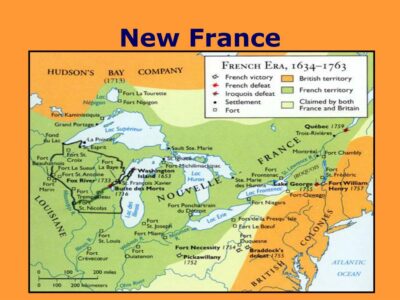

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.