On the twenty-fourth of March 1745 the fleet, consisting of about ninety transports, escorted by the provincial warships, sailed from Nantasket Roads.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 18.

The sarcastic Dr. Douglas, then living at Boston, writes that the expedition had a lawyer for contriver, a merchant for general, and farmers, fishermen, and mechanics for soldiers. In fact, it had something of the character of broad farce, to which Shirley himself, with all his ability and general good sense, was a chief contributor. He wrote to the Duke of Newcastle that though the officers had no experience and the men no discipline, he would take care to provide against these defects, — meaning that he would give exact directions how to take Louisbourg. Accordingly, he drew up copious instructions to that effect. These seem to have undergone a process of evolution, for several distinct drafts of them are preserved.[1] The complete and final one is among the Pepperrell Papers, copied entire in the neat, commercial hand of the general himself.[2] It seems to assume that Providence would work a continued miracle, and on every occasion supply the expedition with weather precisely suited to its wants. “It is thought,” says this singular document, “that Louisbourg may be surprised if they [the French] have no advice of your coming. To effect it you must time your arrival about nine of the clock in the evening, taking care that the fleet be far enough in the offing to prevent their being seen from the town in the daytime.” He then goes on to prescribe how the troops are to land, after dark, at a place called Flat Point Cove, in four divisions, three of which are to march to the back of certain hills a mile and a half west of the town, where two of the three “are to halt and keep a profound silence;” the third continuing its march “under cover of the said hills,” till it comes opposite the Grand Battery, which it will attack at a concerted signal; while one of the two divisions behind the hills assaults the west gate, and the other moves up to support the attack.

The sarcastic Dr. Douglas, then living at Boston, writes that the expedition had a lawyer for contriver, a merchant for general, and farmers, fishermen, and mechanics for soldiers. In fact, it had something of the character of broad farce, to which Shirley himself, with all his ability and general good sense, was a chief contributor. He wrote to the Duke of Newcastle that though the officers had no experience and the men no discipline, he would take care to provide against these defects, — meaning that he would give exact directions how to take Louisbourg. Accordingly, he drew up copious instructions to that effect. These seem to have undergone a process of evolution, for several distinct drafts of them are preserved.[1] The complete and final one is among the Pepperrell Papers, copied entire in the neat, commercial hand of the general himself.[2] It seems to assume that Providence would work a continued miracle, and on every occasion supply the expedition with weather precisely suited to its wants. “It is thought,” says this singular document, “that Louisbourg may be surprised if they [the French] have no advice of your coming. To effect it you must time your arrival about nine of the clock in the evening, taking care that the fleet be far enough in the offing to prevent their being seen from the town in the daytime.” He then goes on to prescribe how the troops are to land, after dark, at a place called Flat Point Cove, in four divisions, three of which are to march to the back of certain hills a mile and a half west of the town, where two of the three “are to halt and keep a profound silence;” the third continuing its march “under cover of the said hills,” till it comes opposite the Grand Battery, which it will attack at a concerted signal; while one of the two divisions behind the hills assaults the west gate, and the other moves up to support the attack.

[1: Shirley to Newcastle, 24 March, 1745. The ministry was not wholly unprepared for this announcement, as Shirley had before reported to it the vote of his Assembly consenting to the expedition. Shirley to Newcastle, 1 February, 1745.]

[2: The first draft of Shirley’s instructions for taking Louisbourg is in the large manuscript volume entitled Siege of Louisbourg, in the library of the Massachusetts Historical Society. The document is called Memo for the attaching of Louisbourg this Spring by Surprise. After giving minute instructions for every movement, it goes on to say that, as the surprise may possibly fail, it will be necessary to send two small mortars and twelve cannon carrying nine-pound balls, “so as to bombard them and endeavor to make Breaches in their walls and then to Storm them.” Shirley was soon to discover the absurdity of trying to breach the walls of Louisbourg with nine-pounders.]

While this is going on, the soldiers of the fourth division are to march with all speed along the shore till they come to a certain part of the town wall, which they are to scale; then proceed “as fast as can be” to the citadel and “secure the windows of the governor’s apartments.” After this follow page after page of complicated details which must have stricken the general with stupefaction. The rocks, surf, fogs, and gales of that tempestuous coast are all left out of the account; and so, too, is the nature of the country, which consists of deep marshes, rocky hills, and hollows choked with evergreen thickets. Yet a series of complex and mutually dependent operations, involving long marches through this rugged and pathless region, was to be accomplished, in the darkness of one April night, by raw soldiers who knew nothing of the country. This rare specimen of amateur soldiering is redeemed in some measure by a postscript in which the governor sets free the hands of the general, thus: “Notwithstanding the instructions you have received from me, I must leave you to act, upon unforeseen emergencies, according to your best discretion.”

On the twenty-fourth of March, the fleet, consisting of about ninety transports, escorted by the provincial cruisers, sailed from Nantasket Roads, followed by prayers and benedictions, and also by toasts drunk with cheers, in bumpers of rum punch.

[It is printed in the first volume of the Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Shirley was so well pleased with it that he sent it to the Duke of Newcastle enclosed in his letter of 1 February, 1745 (Public Record Office).]

[The following letter from John Payne of Boston to Colonel prevailing religious feeling, illustrates the ardor of the New England people towards their rash adventure: —

BOSTON, Apr. 24, 1745.

Sir, — I hope this will find you at Louisbourg with a Bowl of Punch a Pipe and a P — k of C — ds in your hand and whatever else you desire (I had forgot to mention a Pretty French Madammoselle). We are very Impatiently expecting to hear from you, your Friend Luke has lost several Beaver Hatts already concerning the Expedition, he is so very zealous about it that he has turned Poor Boutier out of his House for saying he believed you would not Take the Place. — — Damn his Blood says Luke, let him be an Englishman or a Frenchman and not pretend to be an Englishman when he is a Frenchman in his Heart. If drinking to your success would Take Cape Briton, you must be in Possession of it now, for it’s a standing Toast. I think the least thing you Military Gent^n can do is to send us some arrack when you take ye Place to celebrate your Victory and not to force us to do it in Rum Punch or Luke’s bad wine or sour cyder.

To Collonell Robert Hale at (or near) Louisbourg.

I am indebted for a copy of this curious letter to Robert Hale Bancroft, Esq., a descendant of Colonel Hale.]

On board one of the transports was Seth Pomeroy, gunsmith at Northampton, and now major of Willard’s Massachusetts regiment. He had a turn for soldiering, and fought, ten years later, in the battle of Lake George. Again, twenty years later still, when Northampton was astir with rumors of war from Boston, he borrowed a neighbor’s horse, rode a hundred miles, reached Cambridge on the morning of the battle of Bunker Hill, left his borrowed horse out of the way of harm, walked over Charlestown Neck, then swept by the fire of the ships-of-war, and reached the scene of action as the British were forming for the attack. When Israel Putnam, his comrade in the last war, saw from the rebel breastwork the old man striding, gun in hand, up the hill, he shouted, “By God, Pomeroy, you here! A cannon-shot would waken you out of your grave!”

But Pomeroy, with other landsmen, crowded in the small and malodorous fishing-vessels that were made to serve as transports, was now in the gripe of the most unheroic of maladies. “A terrible northeast storm” had fallen upon them, and, he says, “we lay rolling in the seas, with our sails furled, among prodigious waves.” “Sick, day and night,” writes the miserable gunsmith, “so bad that I have not words to set it forth.”[4] The gale increased and the fleet was scattered, there being, as a Massachusetts private soldier writes in his diary, “a very fierse Storm of Snow, som Rain and very Dangerous weather to be so nigh ye Shore as we was; but we escaped the Rocks, and that was all.”[5]

[4: Diary of Major Seth Pomeroy. I owe the copy before me to the kindness of his descendant, Theodore Pomeroy, Esq.]

[5: Diary of a Massachusetts soldier in Captain Richardson’s company (Papers of Dr. Belknap).]

On Friday, April 5, Pomeroy’s vessel entered the harbor of Canseau, about fifty miles from Louisbourg. Here was the English fishing-hamlet, the seizure of which by the French had first provoked the expedition. The place now quietly changed hands again. Sixty-eight of the transports lay here at anchor, and the rest came dropping in from day to day, sorely buffeted, but all safe. On Sunday there was a great concourse to hear Parson Moody preach an open-air sermon from the text, “Thy people shall be willing in the day of thy power,” concerning which occasion the soldier diarist observes, — “Several sorts of Busnesses was Going on, Som a Exercising, Som a Hearing Preaching.” The attention of Parson Moody’s listeners was, in fact, distracted by shouts of command and the awkward drill of squads of homespun soldiers on the adjacent pasture.

Captain Ammi Cutter, with two companies, was ordered to remain at Canseau and defend it from farther vicissitudes; to which end a blockhouse was also built and mounted with eight small cannon. Some of the armed vessels had been set to cruise off Louisbourg, which they did to good purpose, and presently brought in six French prizes, with supplies for the fortress. On the other hand, they brought the ominous news that Louisbourg and the adjoining bay were so blocked with ice that landing was impossible. This was a serious misfortune, involving long delay, and perhaps ruin to the expedition, as the expected ships-of-war might arrive meanwhile from France. Indeed, they had already begun to appear. On Thursday, the eighteenth, heavy cannonading was heard far out at sea, and again on Friday “the cannon,” says Pomeroy, “fired at a great rate till about 2 of the clock.” It was the provincial cruisers attacking a French frigate, the “Renommée,” of thirty-six guns. As their united force was too much for her, she kept up a running fight, outsailed them, and escaped after a chase of more than thirty hours, being, as Pomeroy quaintly observes, “a smart ship.” She carried dispatches to the governor of Louisbourg, and being unable to deliver them, sailed back for France to report what she had seen.

On Monday, the twenty-second, a clear, cold, windy day, a large ship, under British colors, sailed into the harbor, and proved to be the frigate “Eltham,” escort to the annual mast fleet from New England. On orders from Commander Warren she had left her charge in waiting, and sailed for Canseau to join the expedition, bringing the unexpected and welcome news that Warren himself would soon follow. On the next day, to the delight of all, he appeared in the ship “Superbe,” of sixty guns, accompanied by the “Launceston” and the “Mermaid,” of forty guns each. Here was force enough to oppose any ships likely to come to the aid of Louisbourg; and Warren, after communicating with Pepperrell, sailed to blockade the port, along with the provincial cruisers, which, by order of Shirley, were placed under his command.

The transports lay at Canseau nearly three weeks, waiting for the ice to break up. The time was passed in drilling the raw soldiers and forming them into divisions of four and six hundred each, according to the directions of Shirley. At length, on Friday, the twenty-seventh, they heard that Gabarus Bay was free from ice, and on the morning of the twenty-ninth, with the first fair wind, they sailed out of Canseau harbor, expecting to reach Louisbourg at nine in the evening, as prescribed in the governor’s receipt for taking Louisbourg “while the enemy were asleep.”[6] But a lull in the wind defeated this plan; and after sailing all day, they found themselves becalmed towards night. It was not till the next morning that they could see the town, — no very imposing spectacle, for the buildings, with a few exceptions, were small, and the massive ramparts that belted them round rose to no conspicuous height.

[6: The words quoted are used by General Wolcott in his journal.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 19 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

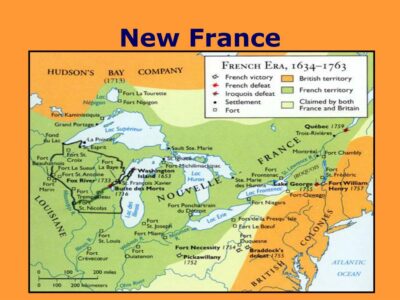

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.