They seized the Grand Battery consisting of twenty-eight forty-two-pounders, and two eighteen-pounders.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 19.

Louisbourg stood on a tongue of land which lay between its harbor and the sea, and the end of which was prolonged eastward by reefs and shoals that partly barred the entrance to the port, leaving a navigable passage not half a mile wide. This passage was commanded by a powerful, battery called the “Island Battery,” being upon a small rocky island at the west side of the channel and was also secured by another detached work called the “Grand,” or “Royal Battery,” which stood on the shore of the harbor, opposite the entrance, and more than a mile from the town. Thus, a hostile squadron trying to force its way in would receive a flank fire from the one battery, and a front fire from the other. The strongest line of defense of the fortress was drawn across the base of the tongue of land from the harbor on one side to the sea on the other, — a distance of about twelve hundred yards. The ditch was eighty feet wide and from thirty to thirty-six feet deep; and the rampart, of earth faced with masonry, was about sixty feet thick. The glacis sloped down to a vast marsh, which formed one of the best defenses of the place. The fortress, without counting its outworks, had embrasures for one hundred and forty-eight cannon; but the number in position was much less, and is variously stated. Pomeroy says that at the end of the siege a little above ninety were found, with “a great number of swivels;” others say seventy-six.[1] In the Grand and Island batteries there were sixty heavy pieces more. Against this formidable armament the assailants had brought thirty-four cannon and mortars, of much inferior weight, to be used in bombarding the fortress, should they chance to fail of carrying it by surprise, “while the enemy were asleep.”[2] Apparently they distrusted the efficacy of their siege-train, though it was far stronger than Shirley had at first thought sufficient; for they brought with them good store of balls of forty-two pounds, to be used in French cannon of that caliber which they expected to capture, their own largest pieces being but twenty-two-pounders.

Louisbourg stood on a tongue of land which lay between its harbor and the sea, and the end of which was prolonged eastward by reefs and shoals that partly barred the entrance to the port, leaving a navigable passage not half a mile wide. This passage was commanded by a powerful, battery called the “Island Battery,” being upon a small rocky island at the west side of the channel and was also secured by another detached work called the “Grand,” or “Royal Battery,” which stood on the shore of the harbor, opposite the entrance, and more than a mile from the town. Thus, a hostile squadron trying to force its way in would receive a flank fire from the one battery, and a front fire from the other. The strongest line of defense of the fortress was drawn across the base of the tongue of land from the harbor on one side to the sea on the other, — a distance of about twelve hundred yards. The ditch was eighty feet wide and from thirty to thirty-six feet deep; and the rampart, of earth faced with masonry, was about sixty feet thick. The glacis sloped down to a vast marsh, which formed one of the best defenses of the place. The fortress, without counting its outworks, had embrasures for one hundred and forty-eight cannon; but the number in position was much less, and is variously stated. Pomeroy says that at the end of the siege a little above ninety were found, with “a great number of swivels;” others say seventy-six.[1] In the Grand and Island batteries there were sixty heavy pieces more. Against this formidable armament the assailants had brought thirty-four cannon and mortars, of much inferior weight, to be used in bombarding the fortress, should they chance to fail of carrying it by surprise, “while the enemy were asleep.”[2] Apparently they distrusted the efficacy of their siege-train, though it was far stronger than Shirley had at first thought sufficient; for they brought with them good store of balls of forty-two pounds, to be used in French cannon of that caliber which they expected to capture, their own largest pieces being but twenty-two-pounders.

[1: Brown, Cape Breton, 183. Parsons, Life of Pepperrell, 103. An anonymous letter, dated Louisbourg, 4 July, 1745, says that eighty-five cannon and six mortars have been found in the town.]

[2: Memoirs of the Principal Transactions of the Last War, 40.]

According to the Habitant de Louisbourg, the garrison consisted of five hundred and sixty regular troops, of whom several companies were Swiss, besides some thirteen or fourteen hundred militia, inhabitants partly of the town, and partly of neighboring settlements.[3] The regulars were in bad condition. About the preceding Christmas they had broken into mutiny, being discontented with their rations and exasperated with getting no extra pay for work on the fortifications. The affair was so serious that though order was restored, some of the officers lost all confidence in the soldiers; and this distrust proved most unfortunate during the siege. The governor, Chevalier Duchambon, successor of Duquesnel, who had died in the autumn, was not a man to grapple with a crisis, being deficient in decision of character, if not in capacity.

[3: “On fit venir cinq ou six cens Miliciens aux Habitans des environs; ce que, avec ceux de la Ville, pouvoit former treize à quatorze cens hommes.” — Lettre d’un Habitant de Louisbourg. This writer says that three or four hundred more might have been had from Niganiche and its neighborhood, if they had been summoned in time. The number of militia just after the siege is set by English reports at 1,310. Parsons, 103.]

He expected an attack. “We were informed of the preparations from the first,” says the Habitant de Louisbourg. Some Indians, who had been to Boston, carried to Canada the news of what was going on there; but it was not believed, and excited no alarm.[4] It was not so at Louisbourg, where, says the French writer just quoted, “we lost precious moments in useless deliberations and resolutions no sooner made than broken. Nothing to the purpose was done, so that we were as much taken by surprise as if the enemy had pounced upon us unawares.”

[4: Shirley to Newcastle, 17 June, 1745/, citing letters captured on board a ship from Quebec.]

It was about the twenty-fifth of March[5] when the garrison first saw the provincial cruisers hovering off the mouth of the harbor. They continued to do so at intervals till daybreak of the thirtieth of April, when the whole fleet of transports appeared standing towards Flat Point, which projects into Gabarus Bay, three miles west of the town.[6] On this, Duchambon sent Morpain, captain of a privateer, or “corsair,” to oppose the landing. He had with him eighty men, and was to be joined by forty more, already on the watch near the supposed point of disembarkation.[7] At the same time cannon were fired and alarm bells rung in Louisbourg, to call in the militia of the neighborhood.

[5: 14 March, old style.]

[6: Gabarus Bay, sometimes called “Chapeau Rouge” Bay, is a spacious outer harbor, immediately adjoining Louisbourg.]

[7: Bigot au Ministre, 1 Août, 1745.]

Pepperrell managed the critical work of landing with creditable skill. The rocks and the surf were more dangerous than the enemy. Several boats, filled with men, rowed towards Flat Point; but on a signal from the flagship “Shirley,” rowed back again, Morpain flattering himself that his appearance had frightened them off. Being joined by several other boats, the united party, a hundred men in all, pulled for another landing-place called Fresh-water Cove, or Anse de la Cormorandière, two miles farther up Gabarus Bay. Morpain and his party ran to meet them; but the boats were first in the race, and as soon as the New England men got ashore, they rushed upon the French, killed six of them, captured as many more, including an officer named Boularderie, and put the rest to flight, with the loss, on their own side, of two men

slightly wounded.[8] Further resistance to the landing was impossible, for a swarm of boats pushed against the rough and stony beach, the men dashing through the surf, till before night about two thousand were on shore.[9] The rest, or about two thousand more, landed at their leisure on the next day.

[8: Pepperrell to Shirley, 12 May, 1745. Shirley to Newcastle, 28 October, 1745. Journal of the Siege, attested by Pepperrell and four other chief officers (London, 1746).]

[9: Bigot says six thousand, or two thousand more than the whole New England force, which was constantly overestimated by the French.]

On the second of May Vaughan led four hundred men to the hills near the town, and saluted it with three cheers, — somewhat to the discomposure of the French, though they described the unwelcome visitors as a disorderly crowd. Vaughan’s next proceeding pleased them still less. He marched behind the hills, in rear of the Grand Battery, to the northeast arm of the harbor, where there were extensive magazines of naval stores. These his men set on fire, and the pitch, tar, and other combustibles made a prodigious smoke. He was returning, in the morning, with a small party of followers behind the hills, when coming opposite the Grand Battery, and observing it from the ridge, he saw neither flag on the flagstaff, nor smoke from the barrack chimneys. One of his party was a Cape Cod Indian. Vaughan bribed him with a flask of brandy which he had in his pocket, — though, as the clerical historian takes pains to assure us, he never used it himself, — and the Indian, pretending to be drunk, or, as some say, mad, staggered towards the battery to reconnoiter.[10] All was quiet. He clambered in at an embrasure and found the place empty. The rest of the party followed, and one of them, William Tufts, of Medford, a boy of eighteen, climbed the flagstaff, holding in his teeth his red coat, which he made fast at the top, as a substitute for the British flag, — a proceeding that drew upon him a volley of unsuccessful cannon-shot from the town batteries.[11]

[10: Belknap, ii.]

[11: John Langdon Sibley, in N. E. Hist. and Gen. Register, xxv. 377. The Boston Gazette of 3 June, 1771, has a notice of Tufts’ recent death, with an exaggerated account of his exploit, and an appeal for aid to his destitute family.]

Vaughan then sent this hasty note to Pepperrell: “May it please your Honour to be informed that by the grace of God and the courage of 13 men, I entered the Royal Battery about 9 o’clock, and am waiting for a reinforcement and a flag.” Soon after, four boats, filled with men, approached from the town to reoccupy the battery, — no doubt in order to save the munitions and stores, and complete the destruction of the cannon. Vaughan and his thirteen men, standing on the open beach, under the fire of the town and the Island Battery, plied the boats with musketry, and kept them from landing, till Lieutenant-Colonel Bradstreet appeared with a reinforcement, on which the French pulled back to Louisbourg.

[Vaughan’s party seems to have consisted in all of sixteen men, three of whom took no part in this affair.]

The English supposed that the French in the battery, when the clouds of smoke drifted over them from the burning storehouses, thought that they were to be attacked in force, and abandoned their post in a panic. This was not the case. “A detachment of the enemy,” writes the Habitant de Louisbourg, “advanced to the neighborhood of the Royal Battery.” This was Vaughan’s four hundred on their way to burn the storehouses. “At once we were all seized with fright,” pursues this candid writer, “and on the instant it was proposed to abandon this magnificent battery, which would have been our best defense, if one had known how to use it. Various councils were held, in a tumultuous way. It would be hard to tell the reasons for such a strange proceeding. Not one shot had yet been fired at the battery, which the enemy could not take, except by making regular approaches, as if against the town itself, and by besieging it, so to speak, in form. Some persons remonstrated, but in vain; and so a battery of thirty cannon, which had cost the King immense sums, was abandoned before it was attacked.”

Duchambon says that soon after the English landed, he got a letter from Thierry, the captain in command of the Royal Battery, advising that the cannon should be spiked and the works blown up. It was then, according to the governor, that the council was called, and a unanimous vote passed to follow Thierry’s advice, on the ground that the defenses of the battery were in bad condition, and that the four hundred men posted there could not stand against three or four thousand.[12] The engineer, Verrier, opposed the blowing up of the works, and they were therefore left untouched. Thierry and his garrison came off in boats, after spiking the cannon in a hasty way, without stopping to knock off the trunnions or burn the carriages. They threw their loose gunpowder into the well, but left behind a good number of cannon cartridges, two hundred and eighty large bombshells, and other ordinance stores, invaluable both to the enemy and to themselves. Brigadier Waldo was sent to occupy the battery with his regiment, and Major Seth Pomeroy, the gunsmith, with twenty soldier-mechanics, was set at drilling out the spiked touch-holes of the cannon. There were twenty-eight forty-two-pounders, and two eighteen-pounders.[13] Several were ready for use the next morning, and immediately opened on the town, — which, writes a soldier in his diary, “damaged the houses and made the women cry.” “The enemy,” says the Habitant de Louisbourg, “saluted us with our own cannon, and made a terrific fire, smashing everything within range.”

[12: Duchambon au Ministre, 2 Septembre, 1745. This is the governor’s official report. “Four hundred men,” is perhaps a copyist’s error, the actual number in the battery being not above two hundred.]

[13: Waldo to Shirley, 12 May, 1745. Some of the French writers say twenty-eight thirty-six pounders, while all the English call them forty-twos, — which they must have been, as the forty-two-pound shot brought from Boston fitted them.

Mr. Theodore Roosevelt draws my attention to the fact that cannon were differently rated in the French and English navies of the seventeenth century, and that a French thirty-six carried a ball as large as an English forty-two, or even a little larger.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 19 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

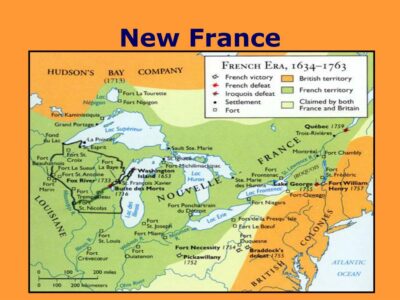

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.