When the levies were complete, it was found that Massachusetts had contributed about 3,300 men, Connecticut 516, and New Hampshire 304 in her own pay, besides 150 paid by her wealthier neighbor.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 18.

Equally zealous, after another fashion, was the Rev. Samuel Moody, popularly known as Father Moody, or Parson Moody, minister of York and senior chaplain of the expedition. Though about seventy years old, he was amazingly tough and sturdy. He still lives in the traditions of York as the spiritual despot of the settlement and the uncompromising guardian of its manners and doctrine, predominating over it like a rough little village pope. The comparison would have kindled his burning wrath, for he abhorred the Holy Father as an embodied Antichrist. Many are the stories told of him by the descendants of those who lived under his rod, and sometimes felt its weight; for he was known to have corrected offending parishioners with his cane.[1] When some one of his flock, nettled by his strictures from the pulpit, walked in dudgeon towards the church door, Moody would shout after him, “Come back, you graceless sinner, come back!” or if any ventured to the alehouse of a Saturday night, the strenuous pastor would go in after them, collar them, drag them out, and send them home with rousing admonition.[2] Few dared gainsay him, by reason both of his irritable temper and of the thick-skinned insensibility that encased him like armor of proof. And while his pachydermatous nature made him invulnerable as a rhinoceros, he had at the same time a rough and ready humor that supplied keen weapons for the warfare of words and made him a formidable antagonist. This commended him to the rude borderers, who also relished the sulphurous theology of their spiritual dictator, just as they liked the raw and fiery liquors that would have scorched more susceptible stomachs. What they did not like was the pitiless length of his prayers, which sometimes kept them afoot above two hours shivering in the polar cold of the unheated meetinghouse, and which were followed by sermons of equal endurance; for the old man’s lungs were of brass, and his nerves of hammered iron. Some of the sufferers ventured to remonstrate; but this only exasperated him, till one parishioner, more worldly wise than the rest, accompanied his modest petition for mercy with the gift of a barrel of cider, after which the parson’s ministrations were perceptibly less exhausting than before. He had an irrepressible conscience and a highly aggressive sense of duty, which made him an intolerable meddler in the affairs of other people, and which, joined to an underlying kindness of heart, made him so indiscreet in his charities that his wife and children were often driven to vain protest against the excesses of his almsgiving. The old Puritan fanaticism was rampant in him; and when he sailed for Louisbourg, he took with him an axe, intended, as he said, to hew down the altars of Antichrist and demolish his idols.[3]

Equally zealous, after another fashion, was the Rev. Samuel Moody, popularly known as Father Moody, or Parson Moody, minister of York and senior chaplain of the expedition. Though about seventy years old, he was amazingly tough and sturdy. He still lives in the traditions of York as the spiritual despot of the settlement and the uncompromising guardian of its manners and doctrine, predominating over it like a rough little village pope. The comparison would have kindled his burning wrath, for he abhorred the Holy Father as an embodied Antichrist. Many are the stories told of him by the descendants of those who lived under his rod, and sometimes felt its weight; for he was known to have corrected offending parishioners with his cane.[1] When some one of his flock, nettled by his strictures from the pulpit, walked in dudgeon towards the church door, Moody would shout after him, “Come back, you graceless sinner, come back!” or if any ventured to the alehouse of a Saturday night, the strenuous pastor would go in after them, collar them, drag them out, and send them home with rousing admonition.[2] Few dared gainsay him, by reason both of his irritable temper and of the thick-skinned insensibility that encased him like armor of proof. And while his pachydermatous nature made him invulnerable as a rhinoceros, he had at the same time a rough and ready humor that supplied keen weapons for the warfare of words and made him a formidable antagonist. This commended him to the rude borderers, who also relished the sulphurous theology of their spiritual dictator, just as they liked the raw and fiery liquors that would have scorched more susceptible stomachs. What they did not like was the pitiless length of his prayers, which sometimes kept them afoot above two hours shivering in the polar cold of the unheated meetinghouse, and which were followed by sermons of equal endurance; for the old man’s lungs were of brass, and his nerves of hammered iron. Some of the sufferers ventured to remonstrate; but this only exasperated him, till one parishioner, more worldly wise than the rest, accompanied his modest petition for mercy with the gift of a barrel of cider, after which the parson’s ministrations were perceptibly less exhausting than before. He had an irrepressible conscience and a highly aggressive sense of duty, which made him an intolerable meddler in the affairs of other people, and which, joined to an underlying kindness of heart, made him so indiscreet in his charities that his wife and children were often driven to vain protest against the excesses of his almsgiving. The old Puritan fanaticism was rampant in him; and when he sailed for Louisbourg, he took with him an axe, intended, as he said, to hew down the altars of Antichrist and demolish his idols.[3]

[1: Tradition told me at York by Mr. N. Marshall.]

[2: Lecture of Ralph Waldo Emerson, quoted by Cabot, Memoir of Emerson, i. 10.]

[3: Moody found sympathizers in his iconoclastic zeal. Deacon John Gray of Biddeford wrote to Pepperrell: “Oh that I could be with you and dear Parson Moody in that church [at Louisbourg] to destroy the images there set up, and hear the true Gospel of our Lord and Saviour there preached!”]

Shirley’s choice of a commander was perhaps the best that could have been made; for Pepperrell joined to an unusual popularity as little military incompetency as anybody else who could be had. Popularity, we have seen, was indispensable, and even company officers were appointed with an eye to it. Many of these were well-known men in rustic neighborhoods, who had raised companies in the hope of being commissioned to command them. Others were militia officers recruiting under orders of the governor. Thus, John Storer, major in the Maine militia, raised in a single day, it is said, a company of sixty-one, the eldest being sixty years old, and the youngest sixteen.[4] They formed about a quarter of the fencible population of the town of Wells, one of the most exposed places on the border. Volunteers offered themselves readily everywhere; though the pay was meagre, especially in Maine and Massachusetts, where in the new provincial currency it was twenty-five shillings a month, — then equal to fourteen shillings sterling, or less than sixpence a day,[5] the soldier furnishing his own clothing and bringing his own gun. A full third of the Massachusetts contingent, or more than a thousand men, are reported to have come from the hardy population of Maine, whose entire fighting force, as shown by the muster-rolls, was then but 2,855.[6] Perhaps there was not one officer among them whose experience of war extended beyond a drill on muster day and the sham fight that closed the performance, when it generally happened that the rustic warriors were treated with rum at the charge of their captain, to put them in good humor, and so induce them to obey the word of command.

[4: Bourne, Hist. of Wells and Kennebunk, 371.]

[5: Gibson, Journal; Records of Rhode Island, v. Governor Wanton of that province says, with complacency, that the pay of Rhode Island was twice that of Massachusetts.]

[6: Parsons, Life of Pepperrell, 54.]

As the three provinces contributing soldiers recognized no common authority nearer than the King, Pepperrell received three several commissions as lieutenant-general, — one from the governor of Massachusetts, and the others from the governors of Connecticut and New Hampshire; while Wolcott, commander of the Connecticut forces, was commissioned as major-general by both the governor of his own province and that of Massachusetts. When the levies were complete, it was found that Massachusetts had contributed about 3,300 men, Connecticut 516, and New Hampshire 304 in her own pay, besides 150 paid by her wealthier neighbor.[7] Rhode Island had lost faith and disbanded her 150 men; but afterwards raised them again, though too late to take part in the siege.

[7: Of the Massachusetts contingent, three hundred men were raised and maintained at the charge of the merchant James Gibson.]

Each of the four New England colonies had a little navy of its own, consisting of from one to three or four small armed vessels; and as privateering — which was sometimes a euphemism for piracy where Frenchmen and Spaniards were concerned — was a favorite occupation, it was possible to extemporize an additional force in case of need. For a naval commander, Shirley chose Captain Edward Tyng, who had signalized himself in the past summer by capturing a French privateer of greater strength than his own. Shirley authorized him to buy for the province the best ship he could find, equip her for fighting, and take command of her. Tyng soon found a brig to his mind, on the stocks nearly ready for launching. She was rapidly fitted for her new destination, converted into a frigate, mounted with 24 guns, and named the “Massachusetts.” The rest of the naval force consisted of the ship “Caesar,” of 20 guns; a vessel called the “Shirley,” commanded by Captain Rous, and also carrying 20 guns; another, of the kind called a “snow,” carrying 16 guns; one sloop of 12 guns, and two of 8 guns each; the “Boston Packet,” of 16 guns; two sloops from Connecticut of 16 guns each; a privateer hired in Rhode Island, of 20 guns; the government sloop “Tartar,” of the same colony, carrying 14 carriage guns and 12 swivels; and, finally, the sloop of 14 guns which formed the navy of New Hampshire.

[The list is given by Williamson, ii. 227.]

It was said, with apparent reason, that one or two heavy French ships-of-war — and a number of such was expected in the spring — would outmatch the whole colonial squadron, and, after mastering it, would hold all the transports at mercy; so that the troops on shore, having no means of return and no hope of succor, would be forced to surrender or starve. The danger was real and serious, and Shirley felt the necessity of help from a few British ships-of-war. Commodore Peter Warren was then with a small squadron at Antigua. Shirley sent an express boat to him with a letter stating the situation and asking his aid. Warren, who had married an American woman and who owned large tracts of land on the Mohawk, was known to be a warm friend to the provinces. It is clear that he would gladly have complied with Shirley’s request; but when he laid the question before a council of officers, they were of one mind that without orders from the Admiralty he would not be justified in supporting an attempt made without the approval of the King.[8] He therefore saw no choice but to decline. Shirley, fearing that his refusal would be too discouraging, kept it secret from all but Pepperrell and General Wolcott, or, as others say, Brigadier Waldo. He had written to the Duke of Newcastle in the preceding autumn that Acadia and the fisheries were in great danger, and that ships-of-war were needed for their protection. On this, the duke had written to Warren, ordering him to sail for Boston and concert measures with Shirley “for the annoyance of the enemy, and his Majesty’s service in North America.”[9] Newcastle’s letter reached Warren only two or three days after he had sent back his refusal of Shirley’s request. Thinking himself now sufficiently authorized to give the desired aid, he made all sail for Boston with his three ships, the “Superbe,” “Mermaid,” and “Launceston.” On the way he met a schooner from Boston and learned from its officers that the expedition had already sailed; on which, detaining the master as a pilot, he changed his course and made directly for Canseau, — the place of rendezvous of the expedition, — and at the same time sent orders by the schooner that any king’s ships that might arrive at Boston should immediately join him.

[8: Memoirs of the Principal Transactions of the Last War, 44.]

[9: Ibid., 46. Letters of Shirley (Public Record Office).]

Within seven weeks after Shirley issued his proclamation for volunteers, the preparations were all made, and the unique armament was afloat. Transports, such as they were, could be had in abundance; for the harbors of Salem and Marblehead were full of fishing-vessels thrown out of employment by the war. These were hired and insured by the province for the security of the owners. There was a great dearth of cannon. The few that could be had were too light, the heaviest being of twenty-two-pound caliber. New York lent ten eighteen-pounders to the expedition. But the adventurers looked to the French for their chief supply. A detached work near Louisbourg, called the Grand, or Royal, Battery, was known to be armed with thirty heavy pieces; and these it was proposed to capture and turn against the town, — which, as Hutchinson remarks, was “like selling the skin of the bear before catching him.”

It was clear that the expedition must run for luck against risks of all kinds. Those whose hopes were highest, based them on a belief in the special and direct interposition of Providence; others were sanguine through ignorance and provincial self-conceit. As soon as the troops were embarked, Shirley wrote to the ministers of what was going on, telling them that, accidents apart, four thousand New England men would land on Cape Breton in April, and that, even should they fail to capture Louisbourg, he would answer for it that they would lay the town in ruins, retake Canseau, do other good service to his Majesty, and then come safe home.[85] On receiving this communication, the government resolved to aid the enterprise if there should yet be time, and accordingly ordered several ships-of-war to sail for Louisbourg.

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 18 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

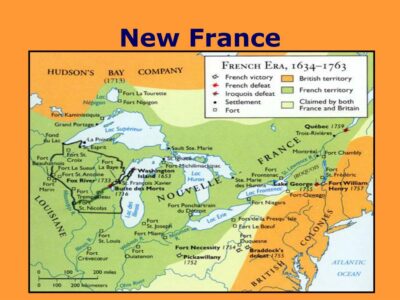

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.