The below narrative rests mainly on contemporary documents, official in character, of which the originals are preserved in the archives of the French Government.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Concluding Chapter 16.

Sixty-two years later, when the vast western regions then called Louisiana had just been ceded to the United States, Captains Lewis and Clark left the Mandan villages with thirty-two men, traced the Missouri to the mountains, penetrated the wastes beyond, and made their way to the Pacific. The first stages of that remarkable exploration were anticipated by the brothers La Vérendrye. They did not find the Pacific, but they discovered the Rocky Mountains, or at least the part of them to which the name properly belongs; for the southern continuation of the great range had long been known to the Spaniards. Their bold adventure was achieved, not at the charge of a government, but at their own cost and that of their father, — not with a band of well-equipped men, but with only two followers.

Sixty-two years later, when the vast western regions then called Louisiana had just been ceded to the United States, Captains Lewis and Clark left the Mandan villages with thirty-two men, traced the Missouri to the mountains, penetrated the wastes beyond, and made their way to the Pacific. The first stages of that remarkable exploration were anticipated by the brothers La Vérendrye. They did not find the Pacific, but they discovered the Rocky Mountains, or at least the part of them to which the name properly belongs; for the southern continuation of the great range had long been known to the Spaniards. Their bold adventure was achieved, not at the charge of a government, but at their own cost and that of their father, — not with a band of well-equipped men, but with only two followers.

The fur-trading privilege which was to have been their compensation had proved their ruin. They were still pursued without ceasing by the jealousy of rival traders and the ire of disappointed partners. “Here in Canada more than anywhere else,” the Chevalier wrote, some years after his return, “envy is the passion à la mode, and there is no escaping it.”[1] It was the story of La Salle repeated. Beauharnois, however, still stood by them, encouraged and defended them, and wrote in their favor to the colonial minister.[2] It was doubtless through his efforts that the elder La Vérendrye was at last promoted to a captaincy in the colony troops. Beauharnois was succeeded in the government by the sagacious and able Galissonière, and he too befriended the explorers. “It seems to me,” he wrote to the minister, “that what you have been told touching the Sieur de la Vérendrye, to the effect that he has been more busy with his own interests than in making discoveries, is totally false, and, moreover, that any officers employed in such work will always be compelled to give some of their attention to trade, so long as the King allows them no other means of subsistence. These discoveries are very costly, and more fatiguing and dangerous than open war.”[3] Two years later, the elder La Vérendrye received the cross of the Order of St. Louis, — an honor much prized in Canada, but which he did not long enjoy; for he died at Montreal in the following December, when on the point of again setting out for the West.

[1: Le Chevalier de la Vérendrye au Ministre, 30 Septembre, 1750.]

[2: La Vérendrye père au Ministre, 1 Novembre, 1746, in Margry, vi. 611.]

[3: La Galissonière au Ministre, 23 Octobre, 1747.]

His intrepid sons survived, and they were not idle. One of them, the Chevalier, had before discovered the river Saskatchewan, and ascended it as far as the forks.[4] His intention was to follow it to the mountains, build a fort there, and thence push westward in another search for the Pacific; but a disastrous event ruined all his hopes. La Galissonière returned to France, and the Marquis de la Jonquière succeeded him, with the notorious François Bigot as intendant. Both were greedy of money, — the one to hoard, and the other to dissipate it. Clearly there was money to be got from the fur-trade of Manitoba, for La Vérendrye had made every preparation and incurred every expense. It seemed that nothing remained but to reap where he had sown. His commission to find the Pacific, with the privileges connected with it, was refused to his sons, and conferred on a stranger. La Jonquière wrote to the minister: “I have charged M. de Saint-Pierre with this business. He knows these countries better than any officer in all the colony.”[5] On the contrary, he had never seen them. It is difficult not to believe that La Jonquière, Bigot, and Saint-Pierre were partners in a speculation of which all three were to share the profits.

[4: Mémoire en abrégé des Établissements et Découvertes faits par le Sieur de la Vérendrye et ses Enfants.]

[5: La Jonquière au Ministre, 27 Février, 1750.]

The elder La Vérendrye, not long before his death, had sent a large quantity of goods to his trading-forts. The brothers begged leave to return thither and save their property from destruction. They declared themselves happy to serve under the orders of Saint-Pierre and asked for the use of only a single fort of all those which their father had built at his own cost. The answer was a flat refusal. In short, they were shamefully robbed. The Chevalier writes: “M. le Marquis de la Jonquière, being pushed hard, and as I thought even touched, by my representations, told me at last that M. de Saint-Pierre wanted nothing to do with me or my brothers.” “I am a ruined man,” he continues. “I am more than two thousand livres in debt and am still only a second ensign. My elder brother’s grade is no better than mine. My younger brother is only a cadet. This is the fruit of all that my father, my brothers, and I have done. My other brother, whom the Sioux murdered some years ago, was not the most unfortunate among us. We must lose all that has cost us so much, unless M. de Saint-Pierre should take juster views, and prevail on the Marquis de la Jonquière to share them. To be thus shut out from the West is to be most cruelly robbed of a sort of inheritance which we had all the pains of acquiring, and of which others will get all the profit.”

[Le Chevalier de la Vérendrye au Ministre, 30 Septembre, 1750.]

His elder brother writes in a similar strain: “We spent our youth and our property in building up establishments so advantageous to Canada; and, after all, we were doomed to see a stranger gather the fruit we had taken such pains to plant.” And he complains that their goods left in the trading-posts were wasted, their provisions consumed, and the men in their pay used to do the work of others.

[Mémoire des Services de Pierre Gautier de la Vérendrye l’aisné, présenté à Mg^r. Rouillé, ministre et secrétaire d’État.]

They got no redress. Saint-Pierre, backed by the governor and the intendant, remained master of the position. The brothers sold a small piece of land, their last remaining property, to appease their most pressing creditors.

[Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, in spite of his treatment of the La Vérendrye brothers, had merit as an officer. It was he who received Washington at Fort Le Bœuf in 1754. He was killed in 1755, at the battle of Lake George. See “Montcalm and Wolfe,” Vol. 1.]

Saint-Pierre set out for Manitoba on the fifth of June, 1750. Though he had lived more or less in the woods for thirty-six years, and though La Jonquière had told the minister that he knew the countries to which he was bound better than anybody else, it is clear from his own journal that he was now visiting them for the first time. They did not please him. “I was told,” he says, “that the way would grow harder and more dangerous as we advanced, and I found, in fact, that one must risk life and property every moment.” Finding himself and his men likely to starve, he sent some of them, under an ensign named Niverville, to the Saskatchewan. They could not reach it, and nearly perished on the way. “I myself was no more fortunate,” says Saint-Pierre. “Food was so scarce that I sent some of my people into the woods among the Indians, — which did not save me from a fast so rigorous that it deranged my health and put it out of my power to do anything towards accomplishing my mission. Even if I had had strength enough, the war that broke out among the Indians would have made it impossible to proceed.”

Niverville, after a winter of misery, tried to fulfil an order which he had received from his commander. When the Indians guided the two brothers La Vérendrye to the Rocky Mountains, the course they took tended so far southward that the Chevalier greatly feared it might lead to Spanish settlements; and he gave it as his opinion that the next attempt to find the Pacific should be made farther towards the north. Saint-Pierre had agreed with him and had directed Niverville to build a fort on the Saskatchewan, three hundred leagues above its mouth. Therefore, at the end of May, 1751, Niverville sent ten men in two canoes on this errand, and they ascended the Saskatchewan to what Saint-Pierre calls the “Rock Mountain.” Here they built a small stockade fort and called it Fort La Jonquière. Niverville was to have followed them; but he fell ill and lay helpless at the mouth of the river in such a condition that he could not even write to his commander.

Saint-Pierre set out in person from Fort La Reine for Fort La Jonquière, over ice and snow, for it was late in November. Two Frenchmen from Niverville met him on the way, and reported that the Assiniboins had slaughtered an entire band of friendly Indians on whom Saint-Pierre had relied to guide him. On hearing this he gave up the enterprise and returned to Fort La Reine. Here the Indians told him idle stories about white men and a fort in some remote place towards the west; but, he observes, “nobody could reach it without encountering an infinity of tribes more savage than it is possible to imagine.”

He spent most of the winter at Fort La Reine. Here, towards the end of February, 1752, he had with him only five men, having sent out the rest in search of food. Suddenly, as he sat in his chamber, he saw the fort full of armed Assiniboins, extremely noisy and insolent. He tried in vain to quiet them, and they presently broke into the guard-house and seized the arms. A massacre would have followed, had not Saint-Pierre, who was far from wanting courage, resorted to an expedient which has more than once proved effective on such occasions. He knocked out the heads of two barrels of gunpowder, snatched a firebrand, and told the yelping crowd that he would blow up them and himself together. At this they all rushed in fright out of the gate, while Saint-Pierre ran after them and bolted it fast. There was great anxiety for the hunters, but they all came back in the evening, without having met the enemy. The men, however, were so terrified by the adventure that Saint-Pierre was compelled to abandon the fort, after recommending it to the care of another band of Assiniboins, who had professed great friendship. Four days after he was gone, they burned it to the ground.

He soon came to the conclusion that farther discovery was impossible, because the English of Hudson Bay had stirred up the western tribes to oppose it. Therefore, he set out for the settlements, and, reaching Quebec in the autumn of 1753, placed the journal of his futile enterprise in the hands of Duquesne, the new governor.

[Journal sommaire du Voyage de Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, chargé de là Découverte de la Mer de l’Ouest (British Museum).]

Canada was approaching her last agony. In the death-struggle of the Seven Years’ War there was no time for schemes of western discovery. The brothers La Vérendrye sank into poverty and neglect. A little before the war broke out, we find the eldest at the obscure Acadian post of Beauséjour, where he wrote to the colonial minister a statement of his services, which appears to have received no attention. After the fall of Canada, the Chevalier de la Vérendrye, he whose eyes first beheld the snowy peaks of the Rocky Mountains, perished in the wreck of the ship “Auguste,” on the coast of Cape Breton, in November, 1761.

[The above narrative rests mainly on contemporary documents, official in character, of which the originals are preserved in the archives of the French Government. These papers have recently been printed by M. Pierre Margry, late custodian of the Archives of the Marine and Colonies at Paris, in the sixth volume of his Découvertes et Établissements des Français dans l’Amérique Septentrionale, — a documentary collection of great value, published at the expense of the American Government. It was M. Margry who first drew attention to the achievements of the family of La Vérendrye, by an article in the Moniteur in 1852. I owe to his kindness the opportunity of using the above-mentioned documents in advance of publication. I obtained copies from duplicate originals of some of the principal among them from the Dépôt des Cartes de la Marine, in 1872. These answer closely, with rare and trivial variations, to the same documents as printed from other sources by M. Margry. Some additional papers preserved in the Archives of the Marine and Colonies have also been used.

My friends, Hon. William C. Endicott, then Secretary of War, and Captain John G. Bourke, Third Cavalry, U. S. A., kindly placed in my hands a valuable collection of Government maps and surveys of the country between the Missouri and the Rocky Mountains visited by the brothers La Vérendrye; and I have received from Captain Bourke, and also from Mr. E. A. Snow, formerly of the Third Cavalry, much information concerning the same region, repeatedly traversed by them in peace and war.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 16 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

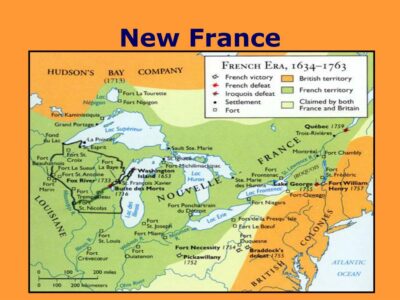

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.