Louisbourg was a standing menace to all the northern British colonies. It was the only French naval station on the continent.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 18.

Annapolis, from the neglect and indifference of the British ministry, was still in such a state of dilapidation that its sandy ramparts were crumbling into the ditches, and the cows of the garrison walked over them at their pleasure. It was held by about a hundred effective men under Major Mascarene, a French Protestant whose family had been driven into exile by the persecutions that followed the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Shirley, governor of Massachusetts, sent him a small reinforcement of militia; but as most of these came without arms, and as Mascarene had few or none to give them, they proved of doubtful value.

Annapolis, from the neglect and indifference of the British ministry, was still in such a state of dilapidation that its sandy ramparts were crumbling into the ditches, and the cows of the garrison walked over them at their pleasure. It was held by about a hundred effective men under Major Mascarene, a French Protestant whose family had been driven into exile by the persecutions that followed the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Shirley, governor of Massachusetts, sent him a small reinforcement of militia; but as most of these came without arms, and as Mascarene had few or none to give them, they proved of doubtful value.

Duvivier and his followers, white and red, appeared before the fort in August, made their camp behind the ridge of a hill that overlooked it, and marched towards the rampart; but being met by a discharge of cannon-shot, they gave up all thoughts of an immediate assault, began a fusillade under cover of darkness, and kept the garrison on the alert all night.

Duvivier had looked for help from the Acadians of the neighboring village, who were French in blood, faith, and inclination. They would not join him openly, fearing the consequences if his attack should fail; but they did what they could without committing themselves, and made a hundred and fifty scaling-ladders for the besiegers. Duvivier now returned to his first plan of an assault, which, if made with vigor, could hardly have failed. Before attempting it, he sent Mascarene a flag of truce to tell him that he hourly expected two powerful armed ships from Louisbourg, besides a reinforcement of two hundred and fifty regulars, with cannon, mortars, and other enginery of war. At the same time he proposed favorable terms of capitulation, not to take effect till the French war-ships should have appeared. Mascarene refused all terms, saying that when he saw the French ships, he would consider what to do, and meanwhile would defend himself as he could.

The expected ships were the “Ardent” and the “Caribou,” then at Louisbourg. A French writer says that when Duquesnel directed their captains to Hail for Annapolis and aid in its capture, they refused, saying that they had no orders from the court.[1] Duvivier protracted the parley with Mascarene, and waited in vain for the promised succor. At length the truce was broken off, and the garrison, who had profited by it to get rest and sleep, greeted the renewal of hostilities with three cheers.

[1: Lettre d’un Habitant de Louisbourg.]

Now followed three weeks of desultory attacks; but there was no assault, though Duvivier had boasted that he had the means of making a successful one. He waited for the ships which did not come, and kept the Acadians at work in making ladders and fire-arrows. At length, instead of aid from Louisbourg, two small vessels appeared from Boston, bringing Mascarene a reinforcement of fifty Indian rangers. This discouraged the besiegers, and towards the end of September they suddenly decamped and vanished. “The expedition was a failure,” writes the Habitant de Louisbourg, “though one might have bet everything on its success, so small was the force that the enemy had to resist us.”

This writer thinks that the seizure of Canseau and the attack of Annapolis were sources of dire calamity to the French. “Perhaps,” he says, “the English would have let us alone if we had not first insulted them. It was the interest of the people of New England to live at peace with us, and they would no doubt have done so, if we had not taken it into our heads to waken them from their security. They expected that both parties would merely stand on the defensive, without taking part in this cruel war that has set Europe in a blaze.”

Whatever might otherwise have been the disposition of the “Bastonnais,” or New England people, the attacks on Canseau and Annapolis alarmed and exasperated them and engendered in some heated brains a project of wild audacity. This was no less than the capture of Louisbourg, reputed the strongest fortress, French or British, in North America, with the possible exception of Quebec, which owed its chief strength to nature, and not to art.

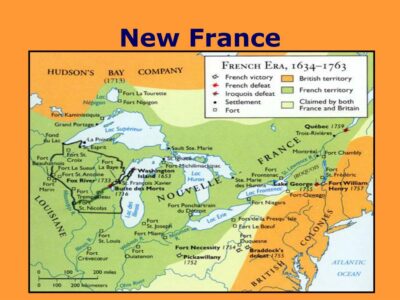

Louisbourg was a standing menace to all the northern British colonies. It was the only French naval station on the continent and was such a haunt of privateers that it was called the American Dunkirk. It commanded the chief entrance of Canada, and threatened to ruin the fisheries, which were nearly as vital to New England as was the fur-trade to New France. The French government had spent twenty-five years in fortifying it, and the cost of its powerful defenses — constructed after the system of Vauban — was reckoned at thirty million livres.

This was the fortress which William Vaughan of Damariscotta advised Governor Shirley to attack with fifteen hundred raw New England militia.[2] Vaughan was born at Portsmouth in 1703, and graduated at Harvard College nineteen years later. His father, also a graduate of Harvard, was for a time lieutenant-governor of New Hampshire. Soon after leaving college, the younger Vaughan — a youth of restless and impetuous activity — established a fishing-station on the island of Matinicus, off the coast of Maine, and afterwards became the owner of most of the land on both sides of the little river Damariscotta, where he built a garrison-house, or wooden fort, established a considerable settlement, and carried on an extensive trade in fish and timber. He passed for a man of ability and force, but was accused of a headstrong rashness, a self-confidence that hesitated at nothing, and a harebrained contempt of every obstacle in his way. Once, having fitted out a number of small vessels at Portsmouth for his fishing at Matinicus, he named a time for sailing. It was a gusty and boisterous March day, the sea was rough, and old sailors told him that such craft could not carry sail. Vaughan would not listen,

but went on board and ordered his men to follow. One vessel was wrecked at the mouth of the river; the rest, after severe buffeting, came safe, with their owner, to Matinicus.

[2: Smollett says that the proposal came from Robert Auchmuty, judge of admiralty in Massachusetts. Hutchinson, Douglas, Belknap, and other well-informed writers ascribe the scheme to Vaughan, while Pepperrell says that it originated with Colonel John Bradstreet. In the Public Record Office there is a letter from Bradstreet, written in 1753, but without address, in which he declares that he not only planned the siege, but “was the Principal Person in conducting it,” — assertions which may pass for what they are worth, Bradstreet being much given to self-assertion.]

Being interested in the fisheries, Vaughan was doubly hostile to Louisbourg, — their worst enemy. He found a willing listener in the governor, William Shirley. Shirley was an English barrister who had come to Massachusetts in 1731 to practice his profession and seek his fortune. After filling various offices with credit, he was made governor of the province in 1741, and had discharged his duties with both tact and talent. He was able, sanguine, and a sincere well-wisher to the province, though gnawed by an insatiable hunger for distinction. He thought himself a born strategist and was possessed by a propensity for contriving military operations, which finally cost him dear. Vaughan, who knew something of Louisbourg, told him that in winter the snow-drifts were often banked so high against the rampart that it could be mounted readily, if the assailants could but time their arrival at the right moment. This was not easy, as that rocky and tempestuous coast was often made inaccessible by fogs and surf; Shirley therefore preferred a plan of his own contriving. But nothing could be done without first persuading his Assembly to consent.

On the ninth of January the General Court of Massachusetts — a convention of grave city merchants and solemn rustics from the country villages — was astonished by a message from the governor to the effect that he had a communication to make, so critical that he wished the whole body to swear secrecy. The request was novel, but being then on good terms with Shirley, the representatives consented, and took the oath. Then, to their amazement, the governor invited them to undertake forthwith the reduction of Louisbourg. The idea of an attack on that redoubtable fortress was not new. Since the autumn, proposals had been heard to petition the British ministry to make the attempt, under a promise that the colonies would give their best aid. But that Massachusetts should venture it alone, or with such doubtful help as her neighbors might give, at her own charge and risk, though already insolvent, without the approval or consent of the ministry, and without experienced officers or trained soldiers, was a startling suggestion to the sober-minded legislators of the General Court. They listened, however, with respect to the governor’s reasons, and appointed a committee of the two houses to consider them. The committee deliberated for several days, and then made a report adverse to the plan, as was also the vote of the Court.

Meanwhile, in spite of the oath, the secret had escaped. It is said that a country member, more pious than discreet, prayed so loud and fervently, at his lodgings, for light to guide him on the momentous question, that his words were overheard, and the mystery of the closed doors was revealed. The news flew through the town, and soon spread through all the province.

After his defeat in the Assembly, Shirley returned, vexed and disappointed, to his house in Roxbury. A few days later, James Gibson, a Boston merchant, says that he saw him “walking slowly down King Street, with his head bowed down, as if in a deep study.” “He entered my counting-room,” pursues the merchant, “and abruptly said, ‘Gibson, do you feel like giving up the expedition to Louisbourg?’” Gibson replied that he wished the House would reconsider their vote. “You are the very man I want!” exclaimed the governor.[3] They then drew up a petition for reconsideration, which Gibson signed, promising to get also the signatures of merchants, not only of Boston, but of Salem, Marblehead, and other towns along the coast. In this he was completely successful, as all New England merchants looked on Louisbourg as an arch-enemy.

[3: Gibson, Journal of the Siege of Louisbourg.]

The petition was presented, and the question came again before the Assembly. There had been much intercourse between Boston and Louisbourg, which had largely depended on New England for provisions.[4] The captured militiamen of Canseau, who, after some delay, had been sent to Boston, according to the terms of surrender, had used their opportunities to the utmost, and could give Shirley much information concerning the fortress. It was reported that the garrison was mutinous, and that provisions were fallen short, so that the place could not hold out without supplies from France. These, however, could be cut off only by blockading the harbor with a stronger naval force than all the colonies together could supply. The Assembly had before reached the reasonable conclusion that the capture of Louisbourg was beyond the strength of Massachusetts, and that the only course was to ask the help of the mother-country.[5]

[4: Lettre d’un Habitant de Louisbourg.]

[5: Report of Council, 12 January, 1745.]

The reports of mutiny, it was urged, could not be depended on; raw militia in the open field were no match for disciplined troops behind ramparts; the expense would be enormous, and the credit of the province, already sunk low, would collapse under it; we should fail, and instead of sympathy, get nothing but ridicule. Such were the arguments of the opposition, to which there was little to answer, except that if Massachusetts waited for help from England, Louisbourg would be reinforced and the golden opportunity lost. The impetuous and irrepressible Vaughan put forth all his energy; the plan was carried by a single vote. And even this result was said to be due to the accident of a member in opposition falling and breaking a leg as he was hastening to the House.

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 18 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.